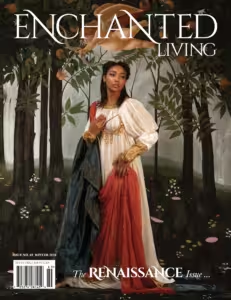

Photographer: STEVE PARKE @steve.parke

Model: TEE PIMENTEL @teepimentel

Wardrobe: JILL ANDREWS GOWNS @jagowns

Muah: NIKKI VERDECCHIA @nikki.verdecchia

Backdrop Paintings: NICHOLE LEAVY ART @nicholeleavyart

Jewelry: PARRISH RELICS @parrish_relics

Photographer’s Assistant: BRITT OLSEN-ECKER @brittolsenecker

We’re gazing into our scrying stones at a new year, eaking open a fresh tarot pack, planning a bright 25 of luscious flavors and fragrances, colors and charms. We’ve always been artists, but this year we’re itching to try something new: bake ourselves some jewelry, write a poem full of predictions and wishes, pick up a brush and paint a self- portrait—treat ourselves as the raw materials for new lives.

Welcome to your own personal Renaissance. Are you ready to be refreshed?

The cycles of birth, growth, decay, and rebirth are what define time itself: seasons of the year, transitions of history. So let’s go back about five and a half centuries and say it’s 1475. You’ve lived through a bleak time, what with the Black Plague (1347, then again and again) and the so-called Holy Wars that finally ended (more or less) in 1453, when Constantinople passed from the Byzantine Empire to the Ottoman Empire. Lately you’ve noticed that the world is more interested in business than in religion, which means that you’re mixing more with other cultures in a step toward globalization. People are paying more attention to people. And then you look around a bit more and rediscover the ancient Greeks and Romans: their intricate stories, their passionate gods, their love of the body in art.

Suddenly you know there is no more exciting time to be alive— and to be refashioning yourself into the person you want to be.

For this issue, we re-created the Renaissance with a dazzling dual cover shoot embodying two of the era’s most amazing icons: the Roman goddess Venus and the early Christian martyr Saint Catherine of Alexandria. We pulled these archetypes out of two famous paintings, dressed our model in lush Renaissance attire, stood her in front of exquisite hand-painted backdrops, and asked goddess and saint to speak to us through the centuries. Art and beauty might be eternal, but they must also step out of the frame once in a while, reveal their layers, and remind us who they are.

At first glance, these women could not seem more different. Botticelli’s Primavera (painted in the late 1470s or early 1480s) shows an exuberant festival, with pagan gods welcoming springtime—perfect for the theme of rebirth. Then Raphael’s Saint Catherine of Alexandria (circa 1507) presents a quiet conversation between saint and heavens, a callback to medieval themes of martyrdom and submission. And yet both of them are quintessentially the Renaissance.

What draws goddess and saint together is not who they were but how the artists presented them, the reverence that Botticelli and Raphael shared for the human … sidling all the way over into outright joy. Our talented team of artists felt it too. They utterly reveled in designing and sewing the costumes, painting the scenery, posing, photographing as much of the process as possible, and finding the modern superwomen within the timeless icons.

Indeed, is there any better way to spend a day—or an era?

Goddess of Mysteries

That stately but ethereal figure on our outside cover cannot be anyone other than Venus, goddess of love and beauty. She is an ancient goddess reborn (yes, Botticelli painted that Venus too), a somewhat serious spirit presiding over others’ pleasure: She is one of the ideals to which we aspire. She is also the mother of Cupid, who flies blindfolded over her head, aiming his arrow willy-nilly into a crowd—because you never know when love (or inspiration, or the dawn of a new age) might strike you.

Dating phases of creativity is always dicey, but we’ll go ahead and break the Italian Renaissance down into four major periods: the early gearing-up (1300–1450), the Renaissance generally speaking (1450–1500), the High Renaissance (1500–1520), and a long, lingering, late era (1520–1625) infused with Mannerism, spilling over into the drama of the Baroque. We’ve covered a bit of it all in these pages, from early angels to Queen Elizabeth, and of course, the flourishing art scene.

Botticelli was born around 1445 and belonged to that second phase. He was from a family of goldsmiths (formerly leather tanners), and he lived all his life in one neighborhood in Florence, with some forays to Rome. When he reinvented himself as a painter, he became known for otherworldly, fine- featured, slightly pensive-looking Madonnas. And then came Primavera, and it changed everything.

This huge painting (about 6 ⅔ by 10 ⅓ feet) is a nest of mysteries. We don’t even know what Botticelli might have called it—art historian Giorgio Vasari gave it the name we know, some seventy years after it was made. What we do know is that Primavera was the first large-scale painting of classical gods and goddesses undertaken since the classical era. Here we see Mercury, the Three Graces, Venus, Flora, the wind Zephyrus, and the nymph Chloris. People had heard of these entities but hadn’t seen them portrayed on such a scale. Botticelli’s masterwork is everything that Renaissance humanism and art were about—an expansion of beliefs and references, with a realistic sense of dimension in the space through which painted bodies appeared to move, and love at the center of it all (or just slightly off-center, anyway).

Now take away the party, the friends—just leave Cupid, because he’s part of who Venus is—and the ancient goddess manifests new qualities. Draped in bright colors over a pale gown, with the hint of gold armor over her heart, she is regal, commanding—a strong beauty. She can hold her own in solitude.

Botticelli’s Venus meets our gaze, her head tilted to the side. Flirting a little? Not if we look at her closely. She seems thoughtful, perhaps assessing us. Are we worthy of love?

Her hand lifts in greeting, or maybe she’s just about to make a pronouncement.

We might not have all the answers, but do we really need a reason to celebrate Venus? Shouldn’t life be all about love and abundance anyway?

Goddess of Transformation

To love, and to love beauty, means you have a curious mind and an adventurous streak—you want to experience the world as you find yourself in it. So our modern Venus, embodied by model Tee Pimentel, is not quite so judgy as Botticelli’s. She asks, What is love, anyway? How do you define what’s beautiful in your life? She has a sense of humor; having exchanged Botticelli’s blue-gray gown for one in diaphanous white, she crosses her arms, just on the point of laughing good-heartedly in our faces. But laughter is just one side of her. She’s also dreamy, passionate, serious, inhabiting each mood fully—a truly human goddess. She urges us to embrace all our emotions. And isn’t it just about time?

Our clothes have always signaled who we are to the world, and as our Venus decides to change hers, we discover new mysteries. The layers peel away. Designer Jill Andrews has added luxe elements such as the cloth-of-gold (a modern silk lamé) that glimmers beneath the filmy white overdress. That gold emerges as Venus’s sleeves, showing she’s precious through and through.

But our girl chooses not to stay Venus forever. When she steps into the Tuscan landscape of our second cover—both backgrounds painted marvelously by Nichole Leavy—she slips into a gown of iridescent blue silk chiffon with split sleeves, studded by 150-year-old gold buttons. Perhaps she is one of the

Muses: Clio for history; Polyhymnia for sacred poetry, song, and dance; Thalia for comedy and celebration. Or a new Muse for a modern age that embraces the past …

Why, incidentally, is there no Muse for painting? Some people say it’s because art must be governed by the goddess of beauty. Or maybe all of us are the Muses. Because even a so-called ordinary girl can change the world.

Breaking the Wheel

Take, for example, Raphael’s Saint Catherine of Alexandria, painted with the spiked wheel of her martyrdom, face turned to the heavens in ecstatic conversation. She too has been a guiding spirit for the Renaissance and beyond: intense, intelligent, sure of her convictions and her rightful place. Not afraid to suffer for her beliefs.

Born around 287, Catherine was a princess and a bookworm (girl after our heart) who converted to Christianity at age fourteen. She set about converting other Romans until the emperor Maxentius considered her a problem when she was about eighteen. He sent pagan philosophers to teach her a lesson and bring her back to the official state religion—and she out-debated them, even convinced some of them to adopt the new faith. Naturally, Maxentius threw her in prison. She held firm. He proposed marriage; she refused. But when he condemned her to death, she accepted with grace.

The method of execution was to have been that spiky wheel on which she leans in Raphael’s picture. It was a cruel sentence, with the executioner using the wheel to break victims’ bones and then leaving them to die. But when the wheel came out, Catherine touched it—and it shattered under her hand. So Maxentius ordered the executioner to cut off her head … and instead of blood, her wound ran with milk.

Saint Catherine has endured for more than 1,700 years as a model of intelligence and resolve. In 1428, her voice urged sixteen- year-old Joan of Arc to take charge of the French army; this princess also knew how to be a warrior.

Joan’s heroism was still within living memory when Raffaello Sanzio da Urbino (even his name is a work of art) painted this picture around 1507. His Catherine embodied strength of character and grace, her body twisting away from the wheel that was meant to be her end and up to the heavens in which she trusts. And he painted her in ecstasy, plugged into the divine.

Our modern saint takes Raphael’s version a step further. She’s already shattered the wheel and kicked the pieces away; it doesn’t belong anywhere near her. When we first encounter her, on our inside cover, she meets our eyes immediately—chin up, proud and defiant, with a smile in the corners of her mouth. That’s right, she says, I’m still here. Page a little further into the feature and you’ll see that in her most Raphaelesque pose—eyes toward the sky—she has actually left the painting behind to plant her feet on the modern studio floor and channel the divine into this complicated world.

She shows up several times, too, in the work of Artemisia Gentileschi, who herself withstood torture to tell her own truth (see “When Women Painted the Renaissance” on page 28), and in paintings by Caravaggio, Titian, Vanessa Bell, Dante Gabriel Rossetti, and others.

Catherine is a princess in the very best sense: a brilliant intellectual, a persuasive debater, with a magical-miraculous scorn for anyone who tries to tell her who to be. She doesn’t need a weapon to fight a war; she has her mind and her will, a complexity that might surprise even our Venus. A secret smile between poses hints at even more mysteries to uncover, perhaps a challenge for us …

Will you be a goddess or a saint?

We answer her just as we’d answer our Venus: Why choose? Be one, be both, be anything. This is your Renaissance.