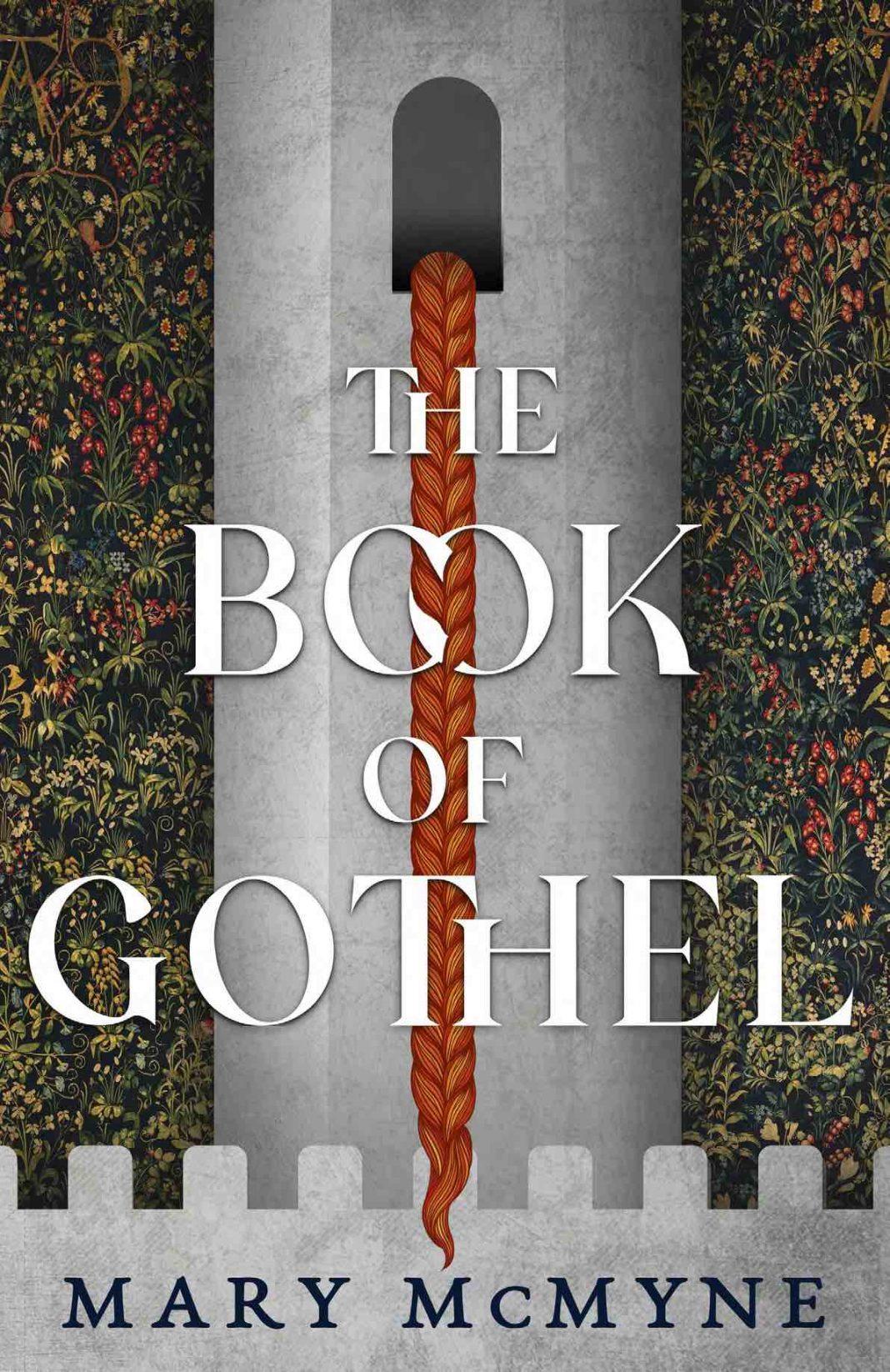

We’re thrilled to talk to our very own poetry editor Mary McMyne about her first novel, The Book of Gothel, which comes out this summer and tells the secret history of Rapunzel from the perspective of the story’s oft-maligned villain.

Enchanted Living: What is The Book of Gothel? Can you describe the book to us?

Mary McMyne: The Book of Gothel is the secret history of Rapunzel, as written by the witch from her legendary tower. It’s a manuscript found buried 800 years later in a Black Forest cellar, which tells the story of a young midwife’s apprentice, shunned by her village.

Haelewise has always lived in the shadow of her midwife mother, Hedda—a woman who will do anything to keep her daughter protected. She has strange black eyes and even stranger fainting spells, and the other villagers fear she is possessed. Haelewise’s only solace lies in the stories her mother tells of child-stealing witches, of princes in wolf skins, of an ancient tower cloaked in mist, where women will find shelter if they are brave enough to seek it.

When Hedda dies, the other villagers blame her for the fever that has been spreading through town, leaving many dead. Fearing for her safety, Haelewise sets out to find the legendary tower her mother used to speak of—a place called Gothel, where Haelewise meets a wise woman willing to take her under her wing. But Haelewise is not the only woman to seek refuge at Gothel. It’s also a haven for a girl named Rika, who carries with her a secret the church strives to keep hidden. Rika introduces Haelewise to a shadow world full of ancient gods and murderous nobles that shimmers behind the world Haelewise has always known.

The Book of Gothel is the story of how Haelewise became the witch who stole away Rapunzel, as well as the original storyteller of other folktales like Snow White and Red Riding Hood. It’s got ancient rituals, decadent feasts with roasted peacock and honeyed wine, love and murder, magic mirrors and wolf skins. It’s got historical characters like Frederick Barbarossa, Beatrice of Burgundy, and Hildegard of Bingen. It’s a love letter to the fairy tales that sustained me when I was little, and a book about giving yourself permission to believe in the impossible.

EL: Why are fairy tales important to you? Why do you think we keep telling and retelling them?

MM: For me, as a child, fairy tales weren’t fictions. They were the lens through which I saw the world. I dropped bread crumbs in the deep dark woods behind my house. I told my little brother about the witch who lived in our rotting barn. I heard her cackle, a high wheezing sound like the wind during hurricane season. At night, when I looked out of my window at the dizzy moon, I heard the howl of the bzou. I can still hear my mother’s voice in my head, telling the tales she told when I was little. When I grew too old for bedtime stories, I read and reread the beautiful leather-bound copies of Grimm and Andersen she and my father gave me. I devoured L’Engle, Tolkien, Carroll, Baum, and Stewart until I could squint, tilt my head, and see the magic in anything. Without this ability, or my parents’ encouragement to read, read, read, I don’t think I would’ve been able to cope with their deaths when I was eighteen and twenty-two. I don’t think I would’ve been inspired to become a writer, to make up stories that create magic out of grief.

For many of us, I believe, fairy tales aren’t fictions. We carry them with us, turn to them in times of need. In fairy tales, as in dreams, murdered girls awaken as if from sleep. Dead mothers and brothers return as birds. Fairy tales fulfill a basic human need; they transform loss into something beautiful. We tell them—and retell them—to make sense of our world.

EL: What made you decide to write a novel retelling fairy tales?

MM: A couple years before I started working on this novel, I gave birth to my first child. When my daughter was one or two, I started reading her fairy tales—trying to re-create my magical childhood. I wanted her to believe in magic, to feel transported the way I had been by my mother’s stories. But as she grew older, she started asking questions about why the female characters in these stories made the decisions they did, and I found the stories—passed down, with a few important exceptions, by a largely male literary tradition—didn’t really answer her questions. I started wondering what the earlier variants women told were like, before they were written down by men.

L: Why did you choose to write about the Rapunzel story specifically?

MM: When I started reading about the history of folktales, I was fascinated with how they changed over time. Some fairy tale authors like the Brothers Grimm claim to have simply recorded the stories that people told them. But the more I read, the more it seemed that the writers revealed their own biases. Charlotte-Rose de la Force, one of the few early women fairy tale writers, for example, seemed to record variants that were much more sympathetic to female characters.

The history of Rapunzel is fascinating! In the three best known written versions, Rapunzel’s kidnapper is portrayed as a cruel ogress who entraps her charge with magic (Basile’s

“Petrosinella”), a much kinder fairy (De La Force’s “Persinette”), and an evil witch (Grimm’s “Rapunzel”). These changes in the witch character intrigued me because they left an uncertainty, a gap that my mind wanted to fill. Who was this woman? There is obviously a long and terrible history in Europe of women being persecuted as witches, especially older or poor women who lived on the fringes of society. I wondered if the witch could’ve been unfairly represented. Was she really that terrible? How would she represent herself?

EL: Can you tell us about the process of writing the book? What started it? How did you research it?

MM: I was working on another novel in which a character finds an ancient manuscript in her grandmother’s cellar. A breathless feeling came over me as I wrote the scene in which the protagonist read the story she found inside, which was written by a peasant woman who claimed she’d been involved in historical events that inspired early variants of several folktales. I fell in love with this woman and her outlandish claims that she was involved in all these stories and met all these famous people. I particularly delighted in her claim that the stories everyone told about her were lies. I set aside the other novel to listen to what Haelewise had to say.

Over time, I gave myself permission to believe in Haelewise’s story, and I realized that I needed to do a lot of reading to portray her world. I devoured books on the history of folktales, medieval German history, the Middle High German language, Jewish life in medieval Europe, medieval women and witchcraft, and medieval conceptions of magic and folk religion.

The following year, I hiked the Black Forest, walking in Haelewise’s footsteps, visiting city museums, marking up my manuscript in my hotel room each night. I visited Saint Hildegard’s rebuilt abbey in Bingen, made a pilgrimage to her shrine, and wandered what is left of her original abbey’s cellar. It was the most magical trip of my life.

Since then, I’ve researched the novel in all sorts of other interesting ways, such as cooking with actual medieval recipes, from meat pies to spiced wine, learning to translate Middle High German literature, and trying to paint illuminations like the ones Haelewise would’ve done for the codex. I won’t comment on the quality of my illuminations, but the spiced wine was delicious!

EL: And, finally, how do you stay enchanted in your everyday life?

MM: Writing, for me, requires giving myself permission to believe in the impossible, so that’s one answer! But I also find that time spent alone outside, in nature, helps me keep my sense of wonder about the world. Every day, I carve out time for interacting with the natural world, observing its beauty and the way it changes with the hours and seasons. Sometimes this means gardening, going on a long walk with my dog, or standing outside at night looking up at the full moon until my neighbors wonder what’s gotten into me. The important thing is that I find time to look for the hidden magic that shimmers just beneath the surface of the world all around me.

The Book of Gothel will be released by Hachette/Orbit/Redhook and Orbit UK on July 26, 2022. Preorders and giveaways are ongoing. Follow Mary McMyne on Instagram or Twitter @marymcmyne, or subscribe to her newsletter at marymcmyne.com to learn more.