If any Pre-Raphaelite woman ever became the image that she portrayed, it was Jane Burden Morris. Although she was a stable hand’s daughter from the (relatively) mean streets of Oxford, Jane made such a remarkable transformation into art royalty that it allegedly inspired the OG Eliza Doolittle in George Bernard Shaw’s 1913 play Pygmalion. Other models appeared as fallen women in Pre- Raphaelite art; Jane almost immediately ascended to her throne and never fell. She truly was the Pre-Raphaelite Queen.

When novelist Henry James met Jane in the late 1860s, he wrote a vivid account of her for his sister: “a tall lean woman in a long dress of some dead purple stuff … an apparition of fearful and wonderful intensity. It’s hard to say … whether she’s an original or a copy. In either case she is a wonder.” It’s not hard to see that the young Henry was in awe of this stately and, more to the point, silent woman (silent because, as he later admits, she had a toothache), and he imbues her with everything he knows of the Pre-Raphaelite vision of her. George Bernard Shaw, onetime suitor of Jane’s daughter May, likewise projected a persona onto Jane, concluding that she was “the silentest woman I have ever met. She did not take much notice of anyone.” Jane’s ability to remain silent in company drew people to fill in blanks, and they used the only evidence of her they felt they could: paintings of her.

The Pre-Raphaelites’ discovery of Jane was intimately tied to her future role as a queen in their work. When Dante Gabriel Rossetti came across her at a theater in Oxford in 1857, he begged her to pose for him and his friends, who were painting murals around the ceiling of the Oxford Union rooms in the colleges (now a library). Jane, with her towering height and halo of black crimped hair, was unlike the small, neat ideal of Victorian feminine beauty, but her imposing presence made her a striking choice for the female lead in their Arthurian vision. In Rossetti’s contribution to one mural, Jane, as a vision of Queen Guinevere, appears in the dreams of Lancelot as a symbol of his sins, preventing him from finding the Holy Grail. Despite the couple’s apparent romance, Rossetti was already avoiding two other women whom he had been romancing and left Jane high and dry as well. This was when Rossetti’s best friend, the shy, retiring, and very rich William Morris, asked to paint Jane, again as a queen.

I’m not saying the girl got typecast—but for her second modeling job, not only was Jane a queen, she was again a queen with fidelity problems. Morris, in a rather shy attempt to romance this stately lass, chose to portray her as the cheating wife of King Mark, La Belle Iseult. Such was his bashfulness, he apparently wrote on the back of the canvas, “I cannot paint you, but I love you.” The inscription renders the subject matter even more puzzling, as he cements his lady love’s persona as the beautiful cheater, the ruination of men. Jane’s repeated portrayal as a queen crowned with infidelity was an unsettling portent of what was to follow.

What is surprising is that Jane either hadn’t noticed the meaning of the roles she was playing for these men or opted to lean into them. After all, had she not risen from being a stable hand’s daughter to leading an enviable lifestyle among the painting elite? In 1860, the year after her marriage to William Morris, the couple collaborated on a wool-thread- on-linen embroidery of the figure of Guinevere, again based on Jane, and worked by them both. Why the Morrises wished to court disaster in a tragic-romantic manner is anyone’s guess, but possibly the answer lies in Morris’s 1858 poem The Defence of Guenevere. Morris imagines a time when Guinevere is charged with adultery, punishable by burning, and she tells her story, her life and loves, her dreary marriage and the rebirth through love for Lancelot. I can see why he would idolize Jane as his perfect woman, his Guinevere, but in marrying her the next year (1859), he became her Arthur—hardly the recipe for a happy marriage.

As a celebration of the marriage of William Morris to Jane, Rossetti painted the pair as Saint George and Princess Sabra in a beautiful 1862 watercolor. As Saint George, William washes the dragon off his hands while watching the villagers carry bits of the slain monster around outside. The grateful, freshly rescued princess kneels, holding up a water bowl and kissing his hands, which is both touching and unhygienic. This is Jane’s brief respite from the series of cheating queens and was one of the few instances where Jane and William appeared together in a painting. Despite being one of the most authentic images of affection, neither George nor Sabra look at each other, and the marked difference in their positions hints at an imbalance in the power dynamic between the pair. Viewing this painting in that light is interesting, particularly in contrast to sketches Rossetti made; in those, William often trails behind his stately bride, trying to make her happy in a bumbling, humorous manner while she remains stoic and unreachable.

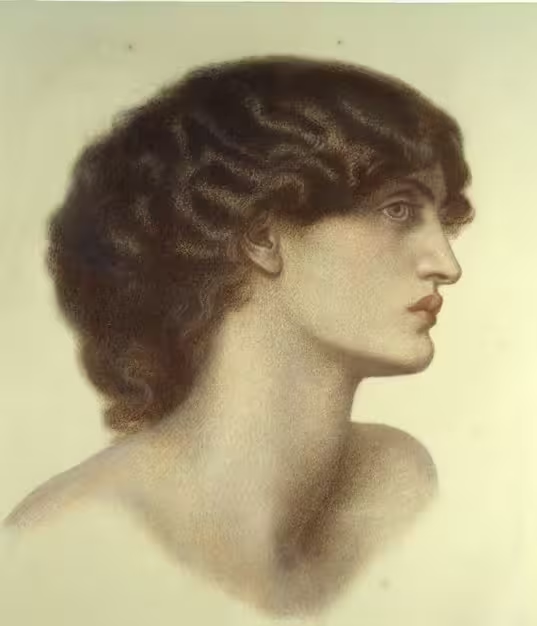

If Jane as Sabra can be written off as Rossetti’s brief moment of generosity toward his friends, his projected series Twelve Coins for One Queen can be seen as a more brutally honest expression of how he came to think of his best friend’s wife. By the late 1860s, Rossetti had developed a morbid fixation on Jane. She became a regal, threatening figure looming out of darkness, haunting his vision in works such as Proserpine (1874), Astarte Syriaca (1876-77), and Mnemosyne (1881). Rossetti’s queen was his wife’s best friend, and an emotional affair between them became a keynote in both their lives. Due to Rossetti’s physical and mental illnesses, the Twelve Coins project—intended to comprise twelve portraits, each with an accompanying poem—was never realized. Only one of the portraits exists, Perlascura (1871), and it is one of the most beautiful and delicate portraits ever done of Jane. The medium is pastels, the composition featuring her shoulders bare and her hair shining. All that is missing is a crown.

The deaths of Rossetti in 1882 and William Morris in 1896 might have meant that Jane’s royal days were over. Yet one more artist came to crown this Pre-Raphaelite queen, but with an interpretation far different from that of the men who had loved her. In Evelyn De Morgan’s 1904-7 painting The Hourglass, Jane is once more enthroned, but she is watching her time coming to an end. Now older, gaunt, and seemingly exhausted, she sits in her finery, watching the sands of an hourglass trickle away. Behind her are medieval tapestries not unlike those she worked on with her husband, and outside she is serenaded by a trumpeting figure of Life. But the rose at her feet has seen better days, and so has she. As her fingers rest on the eponymous hourglass, you wonder if she’s trying to summon the strength to turn it back over and relive those glory days once more—but it is pointless. We all get only one turn of time, and her sand is running out.

Following the death of her husband, Jane lived on in solitude at Kelmscott in Oxfordshire. Although she lived in near obscurity, it was still considered a great honor for undergraduates at Oxford to be brought to meet her in her old age, as if they were being presented at some mythical court.

When Jane died in 1914, her obituaries remembered her as a distinguished beauty and discussed how, with her death, the last link to Pre-Raphaelitism had been broken. The latter claim is indicative of how entirely Jane and her image ruled the idea of Pre-Raphaelitism; models and artists like Annie Miller and Marie Spartali Stillman lived on until the 1920s, but it was Jane’s death that was seen as the official end of the era.

The role of queen bookended Jane’s life, from a tempted, remorseless Guinevere to De Morgan’s mournful, lonely woman watching her time trickle away—a reflection of how women are often seen still. When we’re young and beautiful, we’re accused of inspiring desire in others, but if we age, we’re decried for allowing that lust to die. In many ways, De Morgan’s painting typifies that struggle for women and the way our power rises and then counts down, from our birth to our last desirable day, when we might as well cease to exist. The riches that surround De Morgan’s queen mean nothing, as they’re not where a woman’s power resides.

Jane’s face had raised her from humbleness to wealth, from obscurity to worship. In Shaw’s Pygmalion, Eliza Doolittle’s transformation from flower seller to lady is so complete that Professor Higgins’s former pupil Nepommuck suspects she’s of “the blood royal.” Likewise, in the art she inspired, as well as in the many accounts from admirers and her obituaries, Jane’s humble origins have been overlooked and even concealed. “Queen Jane” reigned from her throne, seeking love from unreliable men with the blessing of her king until the last grain of golden sand fell.

But before we feel too sorry for her, remember that of all her peers raised from working-class origins, she had the most comfortable life. She has also likely had the most books and exhibitions dedicated to her and her work. Her homes are preserved for pilgrims to pay homage. There is no doubt that even in death, Jane still reigns.

Enchanted Living is a quarterly print magazine that celebrates all things enchanted.

Enchanted Living is a quarterly print magazine that celebrates all things enchanted.