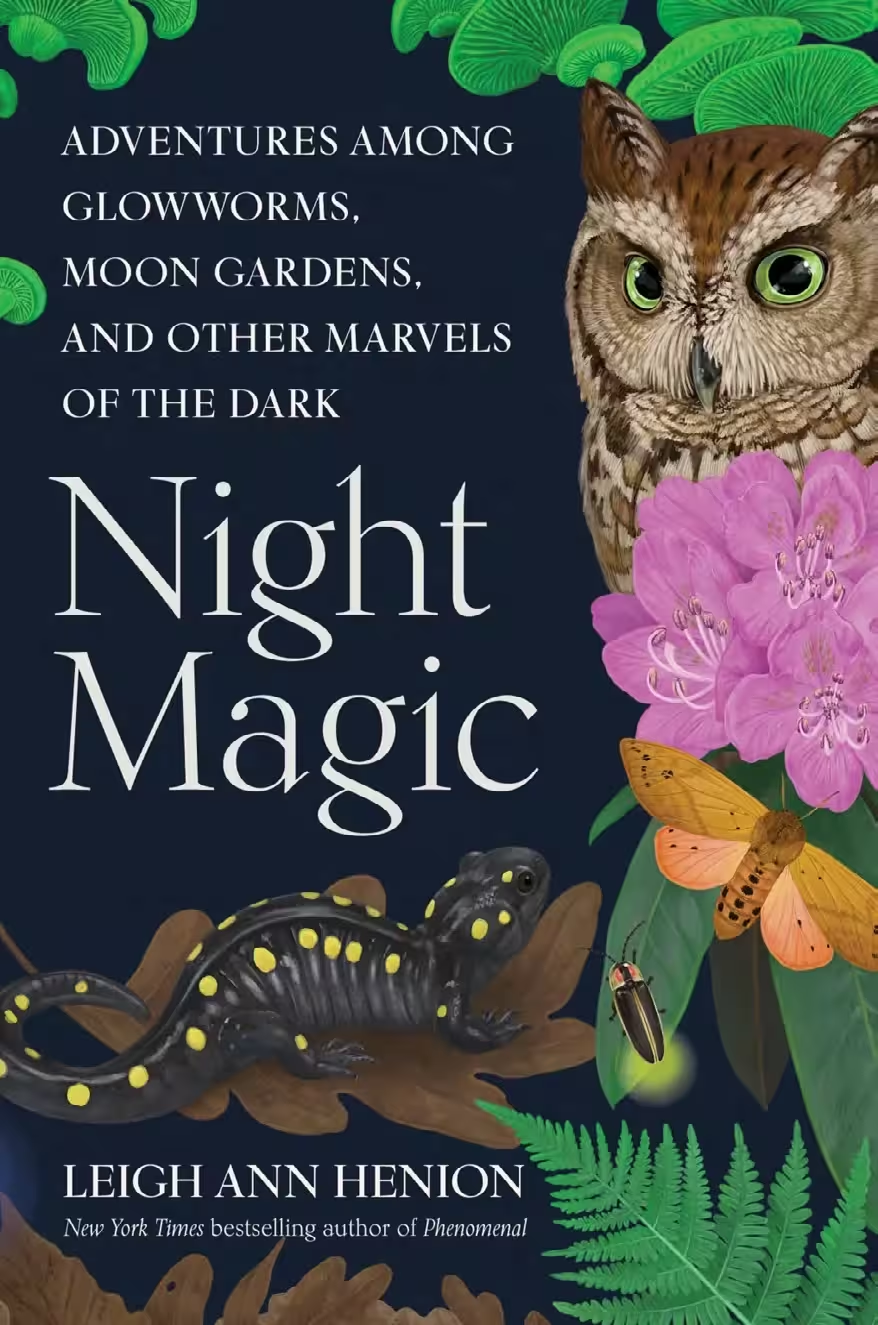

Featured Image:

From the British Library archive / Bridgeman Images

The Night-Blowing Cereus (1807), by Robert Dunkarton

When we saw that New York Times best-selling writer Leigh Ann Henion had a new book coming out this fall about nighttime and all its hidden, glorious enchantments—enchantments fit for an autumn faerie queen, no less, who might even reign in our own backyards—we knew we had to ask her more about it. Night Magic is a celebration of the dark and what goes on in it, “from blooming moon gardens to nocturnal salamanders, from glowing foxfire [to] synchronous fireflies that blink in unison like an orchestra of light.” She forgot long-haired autumnal faerie queens consorting in the deep wood with bats and moths and the occasional deep-forest cake made from black velvet, mushrooms, and moss … but yes, please! We had the following exchange by email and the occasional carrier bat and hawk moth.

Enchanted Living: Can you tell us why you wrote a book called Night Magic? What did you hope to make people see about the night specifically that’s magical?

Leigh Ann Henion: The idea for this book was delivered on firefly wings. After I wrote a magazine article about synchronous fireflies, many readers reached out to let me know that they’d started turning off their porch lights more often. I was amazed that my story had inspired real-world action that led to reduced light pollution, which is a threat to fireflies and a lot of other beings. I was inspired to spend the next few years in the company of owls, moths, salamanders, and other nocturnal creatures to explore natural darkness in an age of increasing artificial light. As I say in the book, I think a loss of habitat leads to a loss of magic—and night is a habitat that’s often underappreciated.

We’ve somehow come to think of it as less important than periods of daylight. But darkness is crucial for life on Earth, and I’ve tried to help recenter darkness— not only as important for the survival of wildlife and ecosystems but also as a valuable part of the human experience.

EL: How might you advise our readers to approach the natural world at night? How should they start to look differently at what inhabits it?

LAH: Experiencing night can sometimes simply mean turning off your own porch lights to sit quietly in observation. It’s increasingly rare to be without some light source—a phone screen or a flashlight, for example. Even when you set out to pointedly experience darkness, it can be hard to find pockets of it. But even in areas of high light pollution, we can often find ways to create tiny pockets of darkness in our own yards, neighborhoods, and communities.

Regionally, there are often unique ways to engage with night. On the West Coast, there are social media groups for people to report bioluminescent waves in the Pacific so that others might catch sight of them. In other regions, there are festivals that celebrate bats and moths to give people a chance to appreciate oft-elusive nocturnal animals. For people nervous about exploring darkness, it can be helpful to find parks and outdoor centers that offer guided night walks to become more comfortable with wandering at night.

EL: Once we create and become accustomed to pockets of dark, what might we look for then?

LAH: I think at first it’s best not to look for anything! Just allow yourself to rest in a space of reduced energy. We tend to catch motion out of the corner of our eyes at night. So it’s helpful to be mindful of that. And to see the glow of foxfire, it’s best to move slowly if you’re taking a night hike. If you find a rich pocket of darkness, you can even just sit still. If you engage with all your senses, unexpected things will likely be revealed.

EL: What are some of the more enchanted creatures and special flora you’ve encountered that flourish in the night?

LAH: If I had to choose one species in Night Magic that seems particularly enchanted, I’d probably settle on blue ghost fireflies. They’re found in various parts of Appalachia, where I live, and I know some extremely stoic people who have been brought to tears by their first sighting of the species. They’re like nothing else I’ve ever seen. Blue ghosts appear neon blue, and they don’t blink like many common species. They stay lit for a long time, so you can track their blue-streaking movements through the forests where they reside. They’re as close to fairies as anything I’ve ever seen. I’ve heard people say that they evoke stories of will-o’-the-wisps, the atmospheric ghost lights of folklore. I think it’s almost impossible to witness a large group of them without being moved by the sheer wonder of the experience.

EL: The theme of this issue is Autumn Queens, and a central idea is an image of a faerie queen, perhaps a bit older than Titania in A Midsummer Night’s Dream. She’s in an autumn forest at night, surrounded by moths and bats and all that autumnal abundance, under a full hunter’s moon … I wonder if you might fill out that image with what you know of nighttime and autumn and magic.

LAH: In autumn, trees pull nutrients from leaves back into their cores to fortify for winter. Animals burrow. I start yearning for tea and blankets and hearth fires. It’s all part of a natural cycle. And longer nights are key in the shift. I’ve always understood that the gorgeous reds and yellows of autumnal leaves had something to do with cooling temperatures, but until researching Night Magic, I had never realized that longer nights play a role in telling photosensitive trees that it’s time to start their process of retreat. Now that I do, it’s hard not to think of the shortening days as a precursor to that arboreal magic. The varied colors of fall are made possible by gathering darkness. It’s fantastic!

And even though fireflies are associated with summer, one of the most amazing things I learned about fireflies early in my research is that they live underground for years before they rise with their own light. We see them only toward the very end of their lives. But in the stages when they’re underground, they continue to glow. So even when I can’t see them in the depths of fall and winter, I now know that I’m still surrounded by their living light. And bioluminescent foxfire—the glow of mushrooms that makes fallen branches look like magic wands—often peaks when cooler temperatures arrive.

Fall eases us into the periods of darkness that are required for us to thrive, just like fireflies. When I started to think of darkness as a place that fosters abundant life, it became easier to loosen my grip on summer and welcome fall as a place of respite.

EL: In your section on autumn, you talk about night-blooming flowers (including the night-blooming cereus), and the bird-size hawk moths that pollinate (some of) them. Can you talk more about these blooms and their seductive powers?

LAH: Before I started contemplating Night Magic, I’d never considered that just as butterflies have whole landscapes of flowers, moths have entire nocturnal ones. Once I realized this, it seemed ridiculously obvious. Still, I’d always overlooked it! There are plenty of books about tending butterfly gardens, yet not all that many talk about moth gardens. Where I live, common primrose is a favorite of hawk moths, which are the size of hummingbirds. And a lot of moth species have favorite plants they depend on as caterpillars.

Persimmon trees, for example, are favorites of luna moths. In certain regions, when you plant native persimmon trees, you’re basically summoning luna moths, clear as a siren call! A lot of night bloomers are nondescript in daylight, but they come alive at night, often blooming rapidly enough that watching is like observing a flower bloom over time-lapse, only you can see them unfurl in real time within minutes. It’s glorious! Night bloomers tend to have strong scents, calling to the giant, gorgeous moths they’ve co-evolved with. Realizing that planting certain species or letting wildflowers grow feral plays a role in where moths congregate—that is a powerful reminder that we’re often in conversation with nocturnal wildlife without realizing it.

EL: The way you describe in your book the giant moths that congregate around moonflowers sounds almost terrifying. When I first saw a luna moth and didn’t know what it was, I admit to being equal parts scared and awestruck. Did you have a response like that to the moths or any of the other creatures you’ve encountered?

LAH: I was in awe of those moths, but I suppose awe can be a mingling of wonder and terror! Of all the creatures I encountered, I think bats made me the most nervous, especially in the beginning. Spending time with biologists and finding ways to have responsible interactions with bats ultimately helped me appreciate them in new ways. Bats, like moths, can be disrupted by the presence of artificial light, which is where humans often encounter them. But in darkness, when they are given the space to do their own thing, encountering them can be marvelous.

EL: How do you feel now when you take a nighttime walk in the wood? What do you see that you didn’t before?

LAH: Before I wrote Night Magic, I had never really walked around at night without light sources for sustained periods of time. When I started exploring after dark, I was surprisingly nervous. Now that I’ve acclimated to some degree, I feel a sense of serenity in the dark. I have had experiences that have helped me understand that sometimes darkness can be an avenue of escape. That’s been very empowering. Now that I am more comfortable with darkness, I can seek shelter in shadows. They aren’t just the domain of potentially frightening things; they’re part of my own natural habitat. And I’m alert to wonders now, whereas before, when I sequestered myself indoors after dusk, I didn’t see or hear or feel much about the night world at all.

EL: Has researching and writing this book changed your life?

LAH: Absolutely. I have come to understand that before exploring night, I only half-knew my own yard and neighborhood. Embracing darkness has literally expanded my world.

EL: Do the moon and stars tie into the magic of the night flora and fauna you’ve encountered?

LAH: When people talk about the wonders of night, they often focus on the moon and stars. But there are living marvels all around us after sunset—and those creatures have their own fantastic relationships to the cosmos. Birds use celestial clues to navigate. It’s thought that carnivorous glowworms—which look like stars scattered on the ground—might be mimicking stars to lure other insects into their silken webs. Large mammals are often more mobile during nights of high illumination. Artificial light tends to be monotone—a complete nocturnal washout—but natural darkness ebbs and flows with reflective moonlight, and those tides have a beauty all their own.

EL: Is there anything more that you hope to share with readers about your book?

LAH: In the process of working on this book, I was often so wowed by discoveries that I had the impulse to reach out to friends immediately because I couldn’t wait to share. As readers ramble through night seasons with me, I hope that at least once they’ll come across something that makes them think, What? I’ve got to tell someone about this!

EL: What natural wonders will you be turning to next?

LAH: A few days ago, I was making breakfast when I saw a giant white bird in a tree downhill from my house. I mean, it was big. I’d just woken up, so it was almost as if I’d dreamed it. When I got a closer look, I couldn’t believe it. They’re not usually spotted on the mountain where I live, but it was a great egret. I’m used to seeing blue herons—and great egrets look very similar in stature—but there was no doubt that this was a bird I’d never seen before. I was in awe even before it took off, with a wingspan that seemed as wide as my arms outstretched. All this to say, I’m not sure what I’ll be turning to next, but I’m trying to stay alert to the natural wonders that turn up unexpectedly!

EL: Can you talk about how you stay enchanted in your everyday life?

LAH: I stay enchanted by trying as much as I can to follow my curiosity. I think enchantment requires an openness to mystery. Years ago, I thought that learning too much about something might erase some of its charm, but the older I get, the more I believe that learning about the nuances of starlight or glowworms or night-blooming flowers leads only to more magic, because when you find answers, they generate more questions. And the more you learn about what humans have discovered, the more you realize how much we still don’t know. To me, staying enchanted means continually chasing and embracing the unknown.

EL: Finally, how often did you think of fairies and other magical creatures as you explored the world at night?

LAH: There has been some limited research that indicates that spending time in natural darkness—with limited point- source illumination—has the capacity to expand humans’ imaginations. One study found that people were more likely to turn to supernatural explanations when answering questions in low-light situations. I think that’s fascinating. When the barrage of the modern world is lessened, it might give us the capacity to think more figuratively, as our ancestors did, pre-electricity. It’s amazing to think that exploring the night world might make us more open to imagining beyond the mundane, and I was often reminded of mythology and folklore and fairy tales in the field. I’ve spent years wandering around with blue ghost fireflies, among flowers that bloom at dusk, and forests full of fungi that glows on the ground like the star stickers that once covered the ceiling of my childhood bedroom. At this point, it’s hard to think of the entire night world as it exists just beyond my backdoor as anything short of magical.

This autumn, find Night Magic, published by Algonquin Books, wherever books are sold. Learn more about Leigh Ann Henion at leighannhenion.com.

Enchanted Living is a quarterly print magazine that celebrates all things enchanted.

Enchanted Living is a quarterly print magazine that celebrates all things enchanted.