Every time my writing gets stuck, I ask myself, “How would Scheherazade get out of this?” Of course, she would know what to do. That’s how she survived for 1,001 nights and beyond: by knowing when to add to a story, when to wrap it up, and when to leave you waiting for the next one. Anyone who understands the power of a story is my kind of hero. Scheherazade was among the first to figure out that the keys to our survival are the stories we tell to ourselves and to others.

I started doing that early on. When I was a child in White Bear Lake, a small town in Minnesota, I used to dress up like Scheherazade for Halloween. I didn’t feel American enough to think the neighbors would let me get away with dressing up as the Bionic Woman or a Charlie’s Angel. But I wanted to be glamorous and gutsy like the women of TV

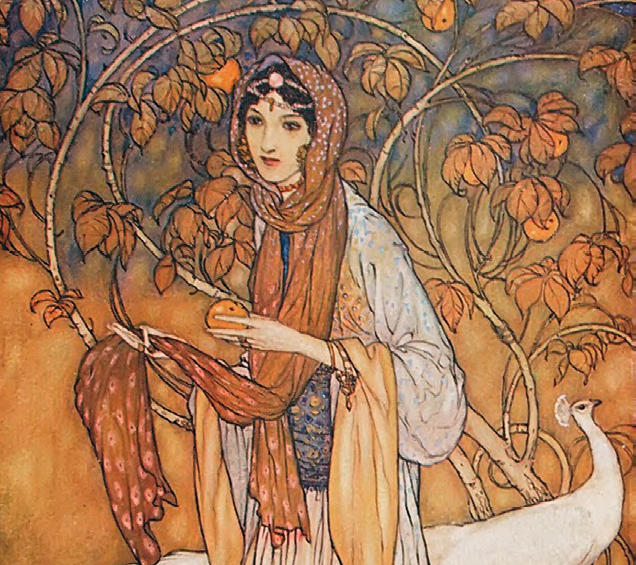

and tabloids. And so I would put on a long dress that some relative I had never met had sent me from Lebanon or Jordan or Palestine and wrap my head in a colorful scarf with fake coins on it. Then I’d have Mrs. Swenson, the mom next door, put some heavy-duty makeup on me, and I’d top it off with gargantuan hoop earrings. Most people thought I was a fortune teller, but I wasn’t a mere soothsayer. I was Scheherazade, the Wonder Woman of the Middle East, the prettiest and most powerful person I knew.

Of course, I didn’t know Scheherazade at all. I certainly didn’t know that she seduced a king with sexually provocative and perverse tales, that she was at the center of a body of work that has kept scholars and historians busy for centuries, and that her collection of tales has become one of the most recognized frameworks in literature. All I knew was based on what my mother told me when I asked why my cousin in Chicago was named Scheherazade—Sherry in its Americanized form. My mother’s answer was the kind of answer a proud Arab woman gives to a girl who cries, like her daughter, at beauty pageants on TV: Scheherazade was the most beautiful woman in the Arab world, which therefore meant the whole world. And she went about being beautiful by swirling around in lots of diaphanous veils and telling stories of magical people—stories that, my mother explained, Disney had stolen for its movies, like the story of Aladdin and Ali Baba and his forty thieves. Soon I also figured out that Scheherazade must have gotten everywhere on a self-chauffeuring magic carpet. This last part I didn’t learn from my mother but rather extrapolated from TV reruns of I Dream of Jeannie, Bewitched, and Saturday-morning cartoons.

In reality, my mother didn’t really know anything more about the Arabian Nights than Walt Disney did. My mother was never one for magic carpets and fairy tales, Orientalist or otherwise. Her stories were always about reality—perhaps embellished reality, but rarely with forever-after happy endings. For her, Scheherazade was a woman who told stories to stay alive to protect her own life but, more important, the lives of her beloved sister and