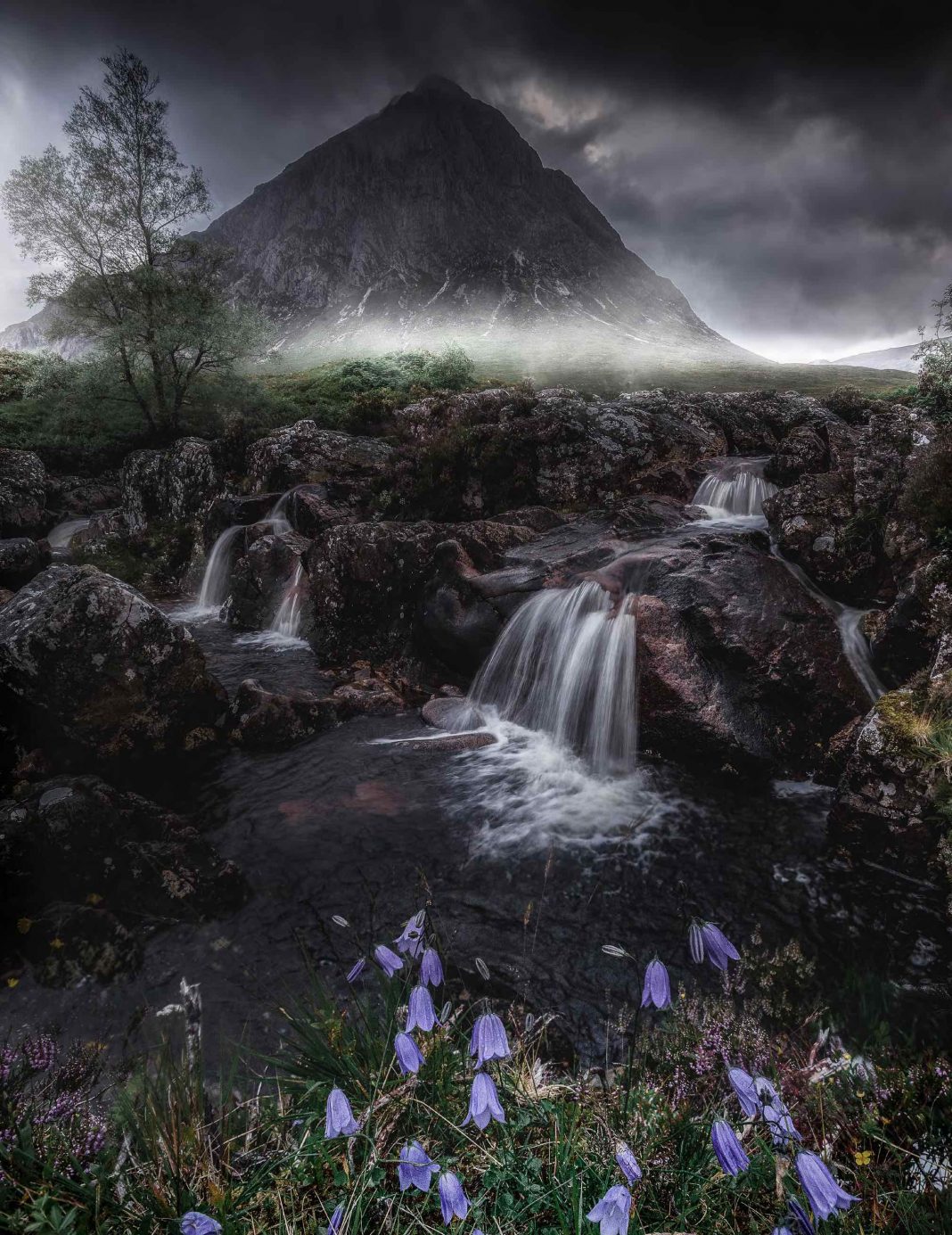

Photography by Mark Callander

Somewhere long ago, in a shady forest pool or a high mountain lake, a woman hovered her palm flat above the water’s surface. Whether this was so she could to meet her twin in the water’s reflection or perhaps just touch the flat of her hand to the liquid’s glassy skin, we cannot know, but she would have felt it—the moment the water shivered up to meet her outstretched hand. Today we recognize that magnetic sensation of water suctioning to skin as a scientific phenomenon called “adhesion.” But in the mist-shrouded millennia that came before science, it was nothing short of magic.

The worship of water—known as hydrology—has been practiced for eons in cultures around the world since time out of memory. One of the most familiar examples comes from India, where the Ganges River is known by Hindus as the goddess Ganga, and her waters are a place to pay homage to ancestors and gods, and wash away earthly sins. In Japan, those of the Shinto faith believe water was protected by the Suijin, a type of spirit believed to embody eels, serpents, or kappa—a greenish-looking “river child” with webbed hands and feet. Spirits also guarded the crystal-clear waters found in the caves of what is now the Yucatán peninsula, where the ancient Maya believed that Chaak, the god of rain, resided. Known as cenotes, these natural sinkholes result from the collapse of limestone bedrock that allows groundwater to rise up, creating life-giving freshwater pools. One cenote acted as an agricultural sundial, for from the opening of the cave, the Maya could track the two days a year when the sun reached its zenith. Another was forbidden for drinking or washing. It was a place of sacrifice, where bodies were dropped to sink into one of the thirteen Maya underworlds.

But few places possess as powerful a link to the belief in enchanted waters as the Celtic world.

In Ireland alone, there are thought to be no less than three thousand holy wells, where pilgrims still travel to tether strips of cloth in nearby trees—wishes, prayers for healing, tributes to the dead. Sacred waters are found in England, Scotland, and Wales as well, secreted away in groves of trees, hollows in the land, at the edge of waysides, and along borders or boundary places, while still others are hidden in ancient underground tunnels, caves, or chambers. If visited in a “thin time,” one might be given a vision of events to come. Some were thought to cure illness—everything from birth defects to maladies like arthritis or leprosy. But the gods could not be summoned without payment in kind. Long before tatters of cloth were tied to trees, offerings were made of butter, cheese, and other precious items, some dating back to the Bronze age. And when it came to wishes made, not all of them were savory. The 130 curse tablets discovered at the Romano-Celtic shrine of Sulis-Minerva in Bath, England, give testament to not only the power citizens believed curses could carry but the nature of their curses as well. “Docimedis has lost two gloves and asks that the thief responsible should lose their minds and eyes in the goddess’ temple,” one reads.

Later, when it became evident in the British Isles that people’s ties to holy wells were too strong to be severed, the sites were adopted by the Christian church, and worship continued under the auspices of Mother Mary, local saints, and Christ. Mothers warned their children up through the 20th century that water from a holy well cannot be brought to boil and the wood from its sacred tree cannot be made to burn, for if a well were abused, it may dry up or shift location. It could result in the disappearance of its sacred fish, the loss of its potency, or even the death of the perpetrator.

Given the tenacity with which Celtic peoples held on to their watery sacred places, it’s perhaps ironic that this body of hydrology is the one scholars know the least about. But we can still learn much by studying the common practices of other cultures. Or better yet, wind your way down the crooked path to the water source yourself. Sit and listen. What do you hear?

While there are still many who recognize the power, natural magic, and vital necessity of water, there’s always more we can do to protect it.

• Never leave the tap running when washing hands, brushing your teeth, or doing the dishes. Also, try shutting off the water while you lather up in the shower. A little conservation goes a long way when we all practice it together.

• Avoid using pesticides or chemical fertilizers and especially avoid hand soaps or cleaning products that contain triclosan, which harms aquatic life.

• Pick up after your pets using eco-friendly bags. Pet waste can run down storm drains, polluting our water with bacteria.

• Never flush or pour medicines or chemical liquid wastes down the drain or toilet.

• Organize a (masked) litter cleanup along a river, beach, or streambed with your family, or bring a bag to pick up litter when walking.