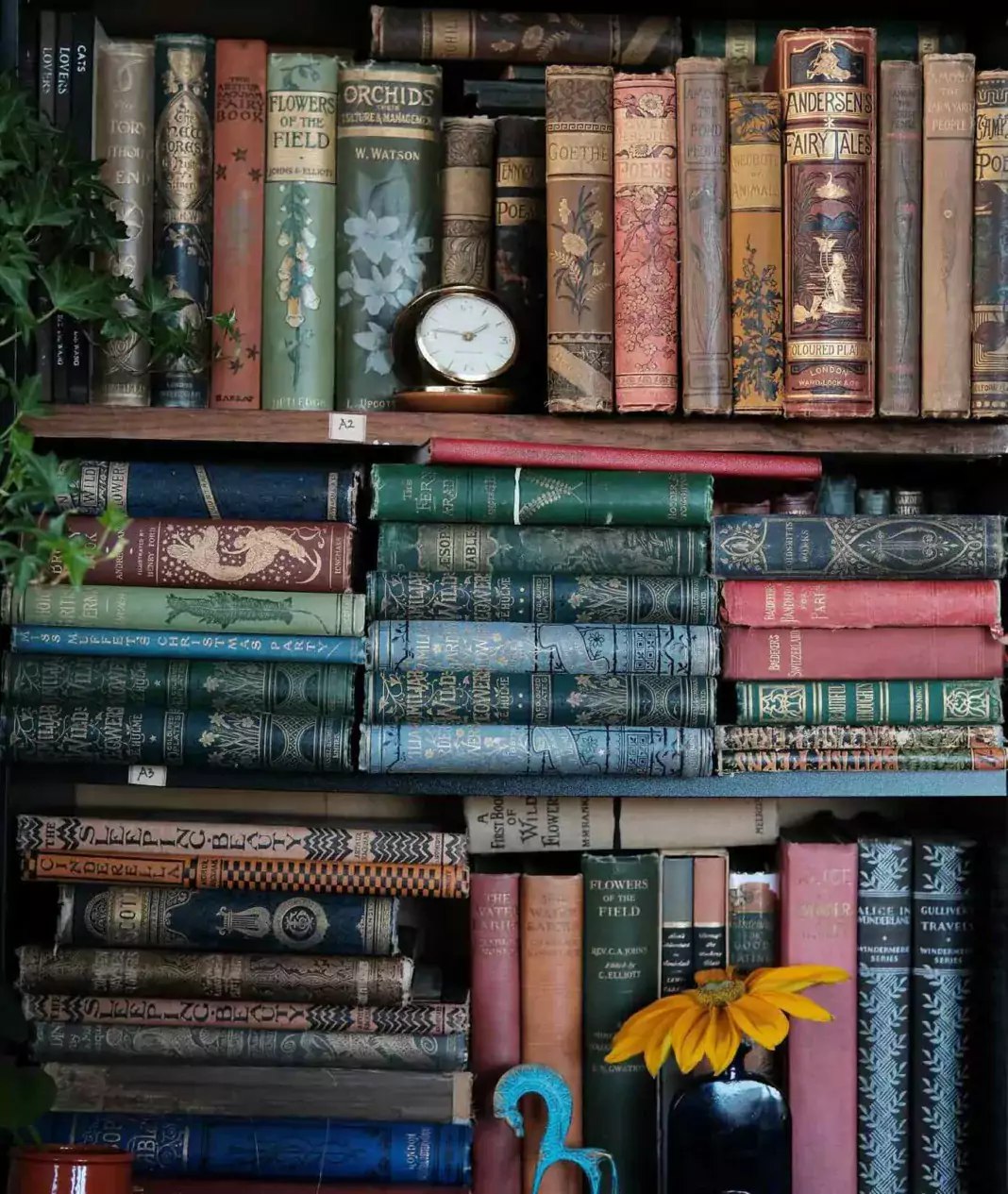

Featured Image:

Book collection by @lescargot.papier

I have a lot of bookshelves, and all of them are magical in some way. But one is the most magical of all.

On the top shelf, you will find Andrew Lang’s Blue Fairy Book; Hans Christian Andersen’s Fairy Tales; Songs of Childhood by Walter de la Mare; a collection of poems called Rainbow Gold, selected by Sara Teasdale; The Little Lame Prince and The Adventures of a Brownie by Miss Mulock; The One-Footed Fairy and Other Stories by Alice Brown; and The Cuckoo Clock by

Mrs. Molesworth. All of these are old editions dating from the late 1800s or early 1900s, with the sorts of things that used to make children’s books so special: embossed covers illuminated with golden details and engraved illustrations inside. They are all a little ragged about the edges, as though handled by children and their parents over generations. And they are filled with magical stories from the time when such stories were first written specifically for children.

Magic was not always considered appropriate for children. The oldest book on that shelf is called The Parent’s Assistant, or Stories for Children, by Maria Edgeworth. I don’t know when my undated copy was printed, but The Parent’s Assistant was first published in 1796. Jane Austen’s heroines might have grown up on Edgeworth’s stories, which have moralistic titles like “Simple Susan” and “Waste Not, Want Not.” My copy certainly looks about 200 years old—the pages have browned, and you can barely see the gilt roses on the spine. In the preface, which is addressed to parents, Edgeworth says children should not read stories about “fairies, giants, and enchanters” because those things are not real. Rather, children should read about other children like themselves, in realistic situations. Edgeworth thought the purpose of children’s stories was to teach useful knowledge and offer moral instruction—which is exactly what her stories do. They are, to be honest, rather boring for a modern reader.

I keep that book because of its historical significance and out of a fondness for its contrarian spirit. It shows us a time when children were not supposed to read fairy tales, before the 19th century opened the doors of fairyland to children and invited them in. It might not be completely fair to Maria Edgeworth that I put her book right next to The Blue Fairy Book, which started the wonderful series of fairy-tale books, each a different color, created by Andrew Lang and his wife, Leonora Alleyne. A generation of children grew up on those fairy books, longing for castles in the air, seven-league boots, and clever talking cats. They were so influential that nowadays, we simply assume children will prefer fantastical stories about a boy invited to attend a school for wizards, or the half-human son of Poseidon, god of the sea. In the battle between realism and fantasy, it’s clear that fantasy eventually won.

On the shelf below, you can find E. Nesbit’s The Phoenix and the Carpet; J.M. Barrie’s Peter and Wendy; Mistress Masham’s Repose by T.H. White; The Hobbit; The Water Babies; The Wind in the Willows, with illustrations by Tasha Tudor; and several of Thornton Burgess’s books about Old Mother West Wind. There is even a book of children’s stories by Louisa May Alcott called Aunt Jo’s Scrap-Bag that I did not know existed until I found it in an antiques shop. It contains a story about what Cinderella’s fairy godmother did after Cinder married the prince, in which magical dressmaking is interwoven with social commentary. Below that, on the third and final shelf, are Nandor Pogány’s Magyar Fairy Tales, English Fairy Tales by Joseph Jacobs, and some modern collections edited by Terri Windling and Ellen Datlow, the fairy godmothers who encouraged so many writers to retell magical tales for adults, with titles like The Fairy Realm and The Wolf at the Door. There are even books realistic and instructive enough

that Maria Edgeworth might have approved of them, such as Johanna Spyri’s Heidi and The Good Master by Kate Seredy (in its original paper cover—a bit torn but still colorful, with motifs from Hungarian embroidery).

What makes this particular bookshelf of mine feel so magical? I suppose it’s partly that the books themselves, with their beautiful old covers, look as though they belonged to an enchantress—as though if you opened them and read a random sentence, you could turn a toad into an accountant and vice versa. Perhaps all books are actually spell books. Consider these first lines:

“In the garden of a mighty King there once grew an apple tree which bore fruit of pure gold.”—Magyar Fairy Tales by Nandor Pogány

“The Mole had been working very hard all the morning, spring-cleaning his little home.” —The Wind in the Willows by Kenneth Grahame

“Old Mother West Wind came down from the Purple Hills in the golden light of the early morning.”—Old Mother West Wind by Thornton Burgess

And of course this famous one:

“In a hole in the ground there lived a hobbit.”—The Hobbit by J.R.R. Tolkien

Don’t they immediately take you to magical places? To the King’s garden with its golden apples (I wonder how they taste?), or Mole’s neat little den, or the Purple Hills, or Bag End, where Bilbo Baggins will begin his adventures? And we too will begin an adventure, because like a magic spell, the words in that book will carry us away from our ordinary lives.

Each book on my shelf is an enchanted box. If you open it, you will be transported and probably changed into something more wonderful than you were before. Meanwhile, lean down and sniff—isn’t the smell of old books magical? Each one in your hand is a precious object, not just because of the story it contains but because of all the other hands that have held it, all the other wanderers in fairyland who have gone before you. When you enter the book, you meet them in spirit. If you met in real life, you would probably be friends—at least you would have some enchanted journeys to talk about.

I have a lot of other bookshelves, and there are a lot of books on them—books that I studied in school, books that I teach from or use for reference, books that I thought I should buy but haven’t had a chance to read yet. But my magical bookshelf stands in the hall, filled with faded old spines and a few new ones, like a constant reminder that books are not just convenient packaging for words. They have an enchantment and beauty all their own.