My husband and I live in a 125-year-old farmhouse where the land has been producing one major crop these days: Fungus. It is thriving. We have trails of wide- capped parasols, shingled colonies of turkey tails and frilly oyster mushrooms, and high up in one tree, a shaggy, slow-growing lion’s mane that we occasionally harvest because eating it is good for the brain. When we first experienced this bounty, I was dismayed to think that these gorgeous, spongy, odd little (or big) miracles are growing from places where our beloved trees are decaying. I’m just glad that they’re there.

Truth is, this hasn’t been a great couple of years for the trees in our neighborhood, as wind or human so-called developers have knocked them down. But it has been a rich and beautiful time for fungus. Some of the magnolias are said to have stood for more than 250 years, and they’re fine, but the line of elms and maples planted along the drive when the house was new have mostly lived out their natural lives, and individual trees have been dying out too. But the underground fungal web that fruits into mushrooms has been here for … who knows how long? And it is having a grand time helping the trees (and itself).

One particular reason to celebrate fungi is their ability to cooperate with other organisms, most especially Kingdom Plantae. Fungus enables a marvelous system of communication within the plant world, and scientists are only just starting to understand how it all works together. The truth is about as bizarre as an episode in one of Lewis Carroll’s Alice books, in which what seems to be completely fantastical breaks down into a logic that not only makes sense but also inspires joy and hope—and reveals an even greater, even more surprising web of sentience, the ability to feel and to make certain connections.

In fact, that’s a good place to start—with Alice. She knows the underground world pretty well.

“Who Are You?”: On Charismatic Species

Without fungus, life on Earth would be unrecognizable. It is all around us (and on us and in us); we just don’t always know how to see it.

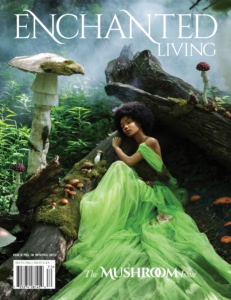

That’s why every kingdom needs a poster child, a charismatic citizen that lures others in and makes them care. The fungus kingdom is not short on that kind of rock star, because mushrooms are glamorous. We take their pictures; we tell their stories. We want to be around them, and we beg them to reveal themselves. We revere them as a symbol of spiritual growth.

So let’s talk for a moment about the most famous mushroom in the history of mushrooms, one of the stars of every version of Alice in Wonderland that has manifested since the book was first published in 1865: that strange fungus upon which a blue Caterpillar sits smoking a hookah. (Rather scandalous, I’ve always thought: Shouldn’t we know what’s in that hookah?) Alice stands up on tiptoes to get a good look, and Chapter 5, “Advice from a Caterpillar,” begins:

The Caterpillar and Alice looked at each other for some time in silence: at last the Caterpillar took the hookah out of its mouth, and addressed her in a languid, sleepy voice.

“Who are you?” said the Caterpillar.

This was not an encouraging opening for a conversation.

Maybe not for Alice, but “Who are you?” (emphasis on both words) had been quite the catchphrase in London around 1841 and after—a way of saying hello in a tavern or, I would guess, a hookah lounge.

Who—or what—is Alice, and how does she fit into this strange world? The plot of Wonderland keeps asking how to classify Alice, physically as well as figuratively. The underground world varies confusingly in scale, and she is constantly caught between returning to her old self and adapting to fit each new setting. Along the way, mistakes are made. Her head might

shoot suddenly through a treetop, or she might nearly drown in a sea of her own tears. This is the adolescent condition; it’s also the human condition: looking for your place amid a messy set of deceptive signals and slippery language, growing, shrinking, “saying what you mean” vs. “meaning what you say,” to borrow from a famous conversation between Alice and the March Hare.

There’s a parallel question in Wonderland for all of us: How do we define the objects and creatures we encounter? Or rather, how do we recognize them for what they are, beyond our own preconceived ideas? That mushroom, for example … It might not be what you’ve always thought it was.

Scientists are only starting to untangle the fungus puzzle—how it lives, where it lives, and even what it is. Our word mushroom seems to derive from the medieval French mousseron, which refers to moss. For most of scientific history, fungus was part of the plant kingdom. But then researchers started to scratch their heads: Fungus does not photosynthesize and turn light into nutrients, as plants do. Its cells are made of chitin, like insects’ and crustaceans’ exoskeletons (which are very close to human hair). It is a heterotroph, meaning it cannot produce its own food; to absorb nutrients, it takes in molecules of other organisms—a fancy way of saying it eats basically the way animals do. Some species (like the turkey tails on our fallen logs) secrete digestive enzymes to hurry the process along.

So since 1968, we have recognized Kingdom Fungi. Long may it flourish!

And keep in mind that as we study it, it might be studying us. In The Light Eaters: How the Unseen World of Plant Intelligence Offers a New Understanding of Life on Earth, author Zoë Schlanger proves that the animal brain is only one form of “mind,” only one way to think of intelligence, memory, decision-making, and sentience. We need to expand our idea of intelligence to embrace other kingdoms.

Because mushrooms might be smart.