Featured Image:

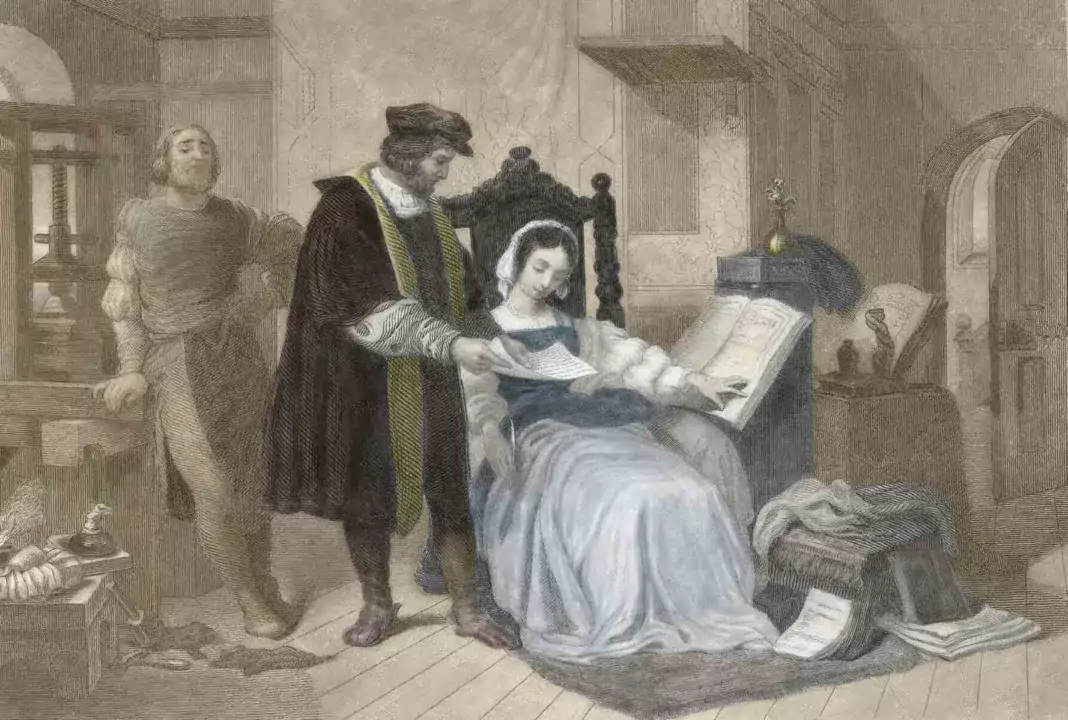

A cutting from the Illustrated London News, March 23, 1850, depicts Johannes Gutenberg showing his wife the firstproof sheet of his Bible printed from movable type. Science History Images / Alamy Stock Photo

That network of shapes crawling across the page are a book’s lifeblood. Sometimes the ink is still unstable, so if you drag your fingers through the words in just the right way, you might smear your own history onto a favorite book. I would never encourage such behavior now—but my first and much-loved paperback of A Tree Grows in Brooklyn was printed quite cheaply with ink that probably stayed damp forever. My eleven-year-old self smeared the type with my fingers and made sure the book registered my presence in it. I could not resist!

Perhaps you already have a favorite recipe for your calligraphy inks. The very first ink formulas go back about 25,000 to 30,000 years (yes, really) and were made with lampblack—a term that covers any kind of soot or charcoal left from burning wood, once ground up and mixed with water. Lampblack lent itself well to variations: Chinese calligraphers cooked the watery solution into more of a gel with the addition of animal-hide glue, plus charred

bone for a deeper shade of black. The Greeks used cephalopod ink from octopuses and squid.

Iron-gall ink, the other big heritage variety, was made from the blisters (galls) that form when certain wasps lay eggs in oak trees—which were pulped and boiled or fermented in wine, water, or vinegar. Iron sulfate turns the deep purple distillate a browner shade. Gum arabic, the sap of North African acacia trees, holds the color in suspension and keeps it smooth.

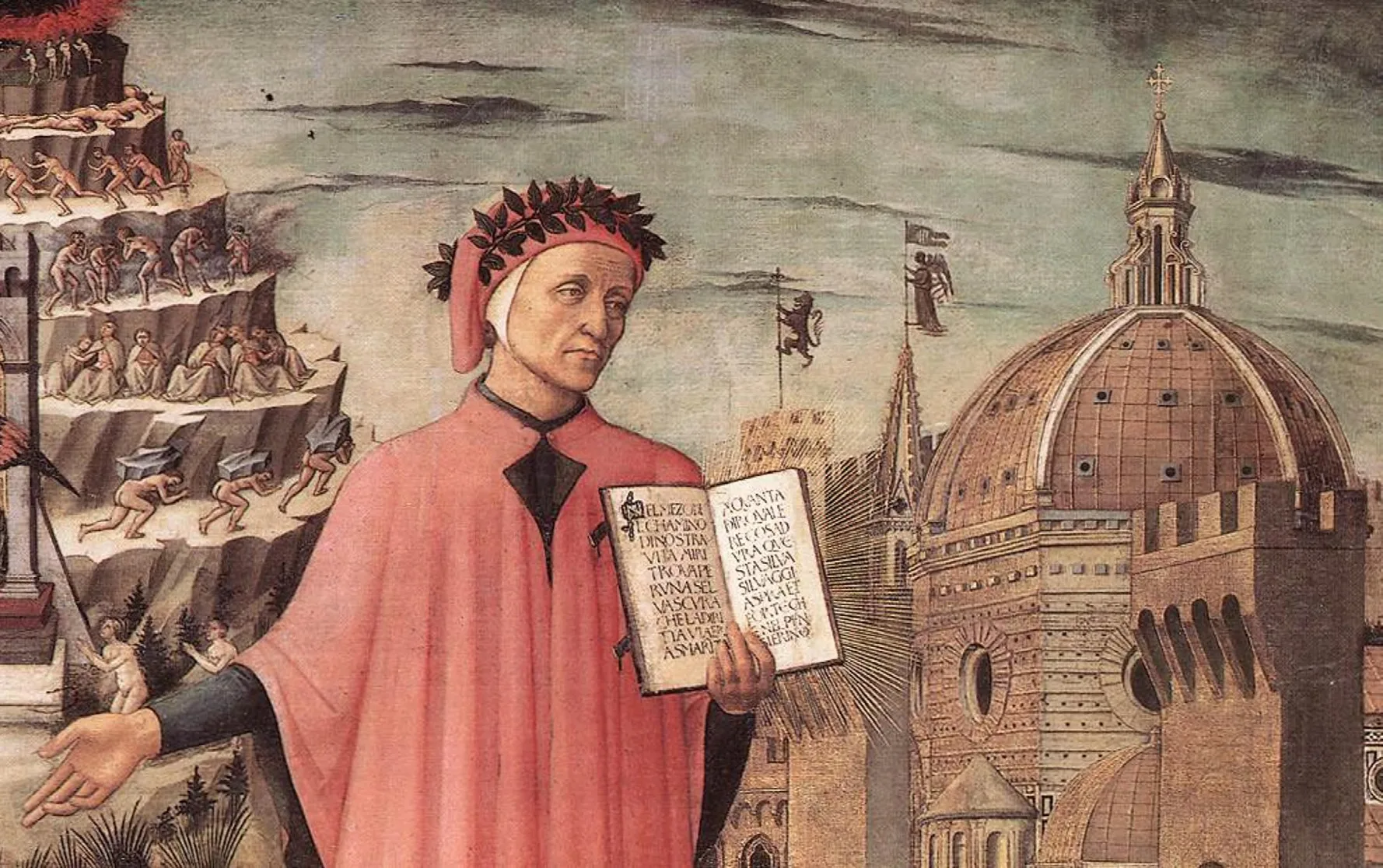

Ink had to evolve suddenly with the invention of the printing press. Johannes Gutenberg started a revolution with movable type: individual metal letters that could be hand-set in a flat wooden plate, or platen (remembering that everything had to be laid out backward). You rolled ink over the type, laid a sheet of paper upon it, and then pressed a plain wooden platen on top. When you’d printed all the pages, you could rearrange and reuse the metal bits.

Under the new technology, ink had to produce a crisp image over and over without dripping or drying out. Gutenberg developed a formula that was more of a colored varnish than a watery dye, cooked up from lampblack and linseed oil, pine resin, oils of turpentine and walnut, cinnabar, and a few elements we have yet to figure out. He and his rival printers kept their recipes ultra-secret, so we don’t know exactly how they conjured the magic.

Gutenberg’s Bibles are among the most sought-after treasures on Earth. The first ones date to 1454, using Saint Jerome’s Latin translation from the late fourth century. Out of 160 to 185 copies printed, 49 are known today. And of course you can’t even get close to touching any of them now—but just think how it must have felt to pull those pages from the press (some made of paper, some of vellum) and spread them to dry. Careful not to smear …

Pity the scribe who feared obsolescence! The new technique was dazzlingly efficient. A monk or a nun might produce three pages a day; Gutenberg could print 3,600. He still had many copies illuminated by hand, which of course took longer and made them more luxe. These books offered the best of both worlds, marrying technology to handmade art.

The contrast in productivity was not just amazing by contemporary standards; it was alarming. In the years just after Gutenberg, a German printer called Johann Fust went to Paris to peddle his wares in the world’s biggest university town. Jealous booksellers cried that the only way he could have so many fine books was with the devil’s help, and he fled in fear of a bonfire and an attempt against his life. Whether this story is true or not—and whether Fust’s bulging inventory came about through a source demonic or divine—it shows that the physical body of the book could stir the most intense passions.

Medieval scribes bent over their vellum fourteen hours a day, scratching out the words of God and poets while others read and prayed aloud to keep all thoughts properly focused. With the printing press, we lost a bit of connection to the human touch

… just as, in the digital age, we now miss the old letterpresses (which are still used to produce glorious artistic editions). There’s a beauty in the occasional smudges and misprints of the old presses—we cherish the misplaced letter or comma as a connection to the human element of the writing.

That’s one reason few books in the Western world are as coveted as the Wicked Bible, a version of the King James published in London in 1631. A printer’s error left out the not from the Seventh Commandment, meaning readers are enjoined, “Thou shalt commit adultery.” (Really? If you say so …)

There is also some Wicked scandal about blots and errata in the word greatness, with the n blotted and the second e misprinted as a. Modesty shall draw a veil—but if I ever find a copy of the Wicked Bible, I pray to be allowed to touch the sinful spot and remember how even with the best of spirits, human invention is fallible.

Lingering on the Edges

Speaking of sensitive, forgotten spots … It seems to have been all too easy to forget that books are a rectangular solid with six sides, not just a front, back, and spine. The page edges are partially hidden, a stretch of secret flesh (as it were) playing peekaboo with the covers.

In the past, edges were ripe for ornamentation, with special textures, colors, and designs laid on. Then with the rise of the paperback and efficiency printing, the three unbound edges of the page became a book’s fallow ground, of special interest to

collectors and antiquarians but woefully neglected by publishers. But then came a moment—this moment—when readers, collectors, and publishers of all kinds have been rediscovering old book production and design elements, investing more in the physical body of their cherished tomes.

For example, consider the edge stain, a flourish first used in the fourth century BCE when someone ran a bit of purple around the pages. Inky edges were standard for many books published more than a hundred years ago. They give an open book a subtle frame, setting it apart as a separate world. I find them magical, so in 2013, I decided to make their restoration my crusade. I begged my editor to bring that antique touch to my novel The Kingdom of Little Wounds. (There may or may not have been actual weeping involved.) It was an easy sell; the designers had never done one, and they got so excited that when publication expenses eventually climbed and I offered to give up the edge, my editor told me very severely that I now had to have one. She could not disappoint the designers, who had decided on a beautiful shade of mulberry that evokes nighttime and blood and magic and secrets. The heart wants what it wants.

Decorated edges are also a most welcome trend in book production these days, and it’s relatively cheap to hire a professional to do what your heart desires. You can even spray edges yourself. Think of this as the tattoo area of your book; you can make it as detailed or elegant as you like. Some spectacular edges have been painted with exquisite mini-masterpieces that

form pictures when the book is closed. Today, custom paintwork can include stencils for words and images such as hearts, stars, bees, skulls, your name, your love’s name—almost anything you can imagine.

Now let’s think about gold. Or silver, for you moon goddesses. Back in the day, a fine library’s books typically bore a thin layer of gold leaf on the top edges of the pages, sometimes all the way around. It looked undeniably posh; it also helped keep insects out of the pages, and the slick finish made those books easy to dust. Please tell me you’ve had your edges gilded! If you’re really splashing out, you can also have them gauffered: Press a pattern into the gilt, or carve the layer of gold with a knife to get a beautiful finish. If colored edges just don’t feel right for your treasured volume, a deckle edge is another very nice touch—and nice to the touch, as the pages on the long side are rough, cut to different lengths, generally giving a feel of an artisanal treasure. The purpose of a deckle edge these days is primarily aesthetic and sensory, but it is also a nod to the history of the book as an object.

You’ve probably noticed that when Jane Austen’s characters read a new release, they do it with a knife in hand. That’s because each sheet that came off the press held four to sixteen pages laid out. The sheet had to be folded one to three times, to make a little packet of double-sided pages. The printer typically did not cut the folds apart, so when you received your new tome, you had to slit the page on at least one side in order to get it open. This was often the case with a book intended for rebinding—meaning the covers in which it was sold were temporary, as the purchaser probably had a library of books that they were binding into uniform covers, spines, ornaments, and edges.

So in The Great Gatsby, when the owlish guest comments that the pages in Gatsby’s library are uncut—and that having cut them would have just been trying too hard—he’s talking about Gatsby’s set decoration for the life he wants to convince others he leads. His books are status symbols, more like furniture than the living entities we know ours are.

A collector keeps things pristine, but a reader wants to free the edges. Bibliophiles will pay extra for an uncut volume; we dream of being the one to release the pages, the first to set eyes upon the text. We crave a bespoke book that’s like no other, whether it’s a beloved classic from childhood or the latest volume of a personal dream journal.

Excesses of Size and Scale

Here is an odd fact about us humans: As soon as we love something, we start wanting to see it in a different size. Make it bigger or smaller—or why not enormous (or tiny). If you think Gulliver’s Travels (for example) is awesome when you

hold it in your hands and read in bed, just think how great it will be if it’s the size of a suitcase—or your thumb …

Jonathan Swift’s satirical adventure about scale and proportion is the source of the bibliophile’s technical terms for big and small books: Brobdingnagiana (really big ones) and Lilliputiana (of a size more at home in a dollhouse than a condo).

Our fascination with size has resulted in coffee-table books that really could serve as coffee tables. Or dining tables. Or barn doors (almost). The first salad days of the Big Book came in the Middle Ages, whose largest surviving manuscript gives heft to the word tome: The Codex Gigas, sometimes known as the Devil’s Bible, is 36 inches long by 20 inches wide, and it weighs 165 pounds. It was created in the early 1200s, when a Bohemian monk called Herman the Recluse broke his vows and was ordered to write down the sum of all human knowledge in one night; if he failed, in the morning he would be walled into a cell for eternity. Herman prayed for help—to Lucifer. His prayer was granted, and in that night of scriptomania, he used 309 or more sheets of parchment (requiring the skins of 100 to 160 donkeys)—and produced some stunning illuminations, one of which is, fittingly, a portrait of Lucifer.

Fine, fine—scholars now say that the Codex Gigas was transcribed over the course of twenty years, not one night, and the devil might not have been involved at all. But you still have to

admire the consistency of the handwriting, which looks like the work of one long, sustained session with quill and inkpot—and a stable’s worth of animal hides. You can see it for yourself now in Stockholm, at rest after eight hundred years and several perilous close calls with destruction.

We don’t know why Herman made his book so darned big, but there was actually a practical reason to commission some Brobdingnagiana in his day: People shared their books, and several might be reading at the same time. Or singing at the same time, more to the point. Medieval antiphonaries, containing Catholic liturgies with words and musical notations, could rest open on a stand, large enough for a choir of monks to see and follow along. When they stood singing in their stalls, limbs wobbly with arthritis, the pure notes twined through the pillars and carvings and pointy windows—a magnificent sound conjured from one enormously inspired book. It would have taken several of those monks to lug an antiphonary around, so if your monastery had one, it pretty much stayed where you left it.

Anyway, since when are books purely practical things? As long as we’re making something fantastic, we might as well make it huge. That was probably what Charles II thought when he was gifted with the Klencke Atlas of 1660, which makes even the Codex Gigas look positively Lilliputian. Six feet tall and more than three and a half feet wide when shut, the Klencke is a marvel

of the era’s technology for mapmaking as well as bookbinding. It was never destined to be a page turner, because the maps inside were meant to be removed and hung on the wall. The bookbinding was mostly for convenience in moving them from one spot to another.

A big book is majestic, yes; it can help a choir carry a tune or plot a voyage through the known world. But there is something to be said for books that go the other direction. Reading is an intimate experience, so there is nothing quite like holding, say, a very little copy of Little Women in the palm of your hand, or The Divine Comedy fitted into a walnut shell. You could loop an entire Lilliputian book on a chain at your neck; then you’d never be short something to read.

By official designation, a miniature book measures below three inches in every direction. Many are produced using a single sheet of paper, printed with 64 mini-book pages and folded so that the pages face the correct direction and follow sequentially. The portability and intimacy help provide comfort and inspiration in unexpected ways. The miniature printed book was especially beloved during the Victorian era—when, incidentally, the invention of aniline chemical inks took inkmaking out of a cottage industry and into factories. Miniature books were a good antidote to the increasing depersonalization of industrial life. Starting in the 1890s, David Bryce of Glasgow, Scotland, gained renown by producing marvels of miniature engineering and design. His focus was on the Bible, but another of his most popular offerings was a miniature Qu’ran (his spelling) that Indian soldiers carried into the trenches of World War I.

That size is also just right for small hands, so many examples of Lilliputiana were children’s Bibles or other instructive works for young minds. One perennial favorite is a little miracle called London Characters, describing various jobs and professions—cunningly tucked inside a cardboard matchbox and billed as “The Safest Series for Children.” Or the delightfully self-referential The Mite, which contains information about the history and process of … printing books. In 1891, it popped off the presses at 21 millimeters by 13, or about three-quarters of an inch by a half-inch. Unsurprisingly, a copy ended up in the greatest miniature library on the planet: the one in Queen Mary’s dollhouse, along with tiny tomes handwritten by the likes of Vita Sackville-West and Arthur Conan Doyle. It was outdone in 1900 with an edition of Omar Khayyam (a.k.a. The Rubaiyat thereof) small enough to fit in place of a jewel in a signet ring.

In 1985, a truly microscopic version of Old King Cole was printed via offset lithography, the same technique newspapers use today. The ink is transferred from the metal type to a rubber roller, which then rolls (logically) over the page to be printed. The result measures just one millimeter by 0.9—about the size of a sharp pencil tip. It is so small it has to be mounted on a card. That merry old soul called for a print run of 85 nearly invisible copies. If you want to read it, you’ll have to use a needle to turn the pages.

I’m going to stop there, with the triumph of a printing process that Gutenberg would still recognize. In the age of silicon, books have become even more unimaginably microscopic, the equivalent of the Kish tablet engraved on a grain of sand … almost figments of the imagination.

Give us something to hold!

Books as Villains

But I must issue a caution: These gorgeous (and sometimes weird) volumes can be fatal. That’s especially true of some of the oldest and rarest and most likely to appeal to the bibliophile.

In particular, you have to watch out for the green ones.

Arsenic has many applications, and the Victorians couldn’t get enough of the stuff, using it for everything from painting a bookbinding brilliant emerald to killing bugs and mice to (through small oral doses) brightening the complexion. Any of those functions can also prove fatal to humans. Decorating a binding often means licking the tip of a paintbrush to get a sharp line. When somebody was painting with arsenic, the results were woefully predictable: burns and lesions in mouth and throat, numbness and tingling in hands and feet, and potentially death.

Even today, you must exercise caution when it comes to what you read and how long you linger over it. The arsenic may work its way out of leather, cloth, and paper to find you. Don’t wait to break out in blisters: If your hands are covered in an eerie green powder, wash them immediately and put the book into a sealed plastic bag. Then call the folks over at the Poison Book Project; they are making a catalog of every volume ever produced with arsenic, and they’d love to have a crack at yours.

Which leads us to the problem of forbidden books.

I would concede that access to some books should be restricted, with arsenic-infused bindings forming one of the top categories. But that’s a problem with the body of the book, its physical being. When it comes to the soul, the essence—well, who are we? Are we for free speech and the right to read what we want, when we want, whether in a beautifully printed edition or a handful of manuscript pages exchanged in a writers’ group? Do we presume to tell others what they can and cannot read, however unpleasant we find their choices? (Hint: No, we do not.)

Say you’ve had a rough day. Felt misunderstood, kicked around, bruised. Your friends haven’t been through what you have; they love you, but they just don’t get this. Where do you turn to find a kindred spirit, one who shows it’s possible to survive what you are enduring, who not only understands you emotionally but also offers a friendly physical form, a rudder by which to steer through rough waters—the comfort of an object that is so much more than the sum of its pages and ink? That’s right, I am prescribing a book (or this magazine). But what if the books that speak to your experience, the ones that put you on the page, have been removed from your library? What if you never

even hear of Gender Queer? Or the Wicked Bible? Or Harry Potter?

That’s right, the bespectacled boy wizard has been banned from many school libraries, because some watchdogs have said he’s too dark and occult and witchy for children.

According to PEN America, an organization supporting human rights and the freedom of literary expression, about fifty groups nationwide are pushing through challenges and bans to books in local and school libraries. Among the most frequently challenged authors are favorites and titans such as Maia Kobabe, Toni Morrison, and Sarah J. Maas. In one school district in Escambia County, Florida, for example, 1,600 books were recently banned or otherwise restricted pending investigation. Five of them were dictionaries, because words are dangerous.

You might have heard that when a book is banned, it’s good for sales; it isn’t. Think of all the libraries that will not have that potentially life-changing book that you crave on the shelves, the bookstores where no one will have heard of it, and the insults and attacks on various social media platforms that will drive readers away. I don’t need to read that book for myself, someone might say, I saw the nasty reviews on Goodreads. Some banned authors have found their library and bookstore events canceled because the sponsoring institutions could not afford the security needed to host them.

Books have real power in the physical and metaphysical worlds. But even arsenic-laced tomes don’t attack people out of malice. When a book is banned, thousands of readers are denied an experience that might mean the world to them—make them feel seen, understood, important, inspired. Without that smeary newsprint copy of a beloved novel, or the miniature sacred text to bring into battle—some beacon of perfectly bound, deckle-edged, heavenly-smelling light—who will we be?

Johann Fust, the printer who fled Paris because he had so many books that shoppers believed Satan must have lent him a hand.

Herman the Recluse, writing impossible passages overnight to save himself from enclaustration.

Or someone whose name we’ll never know, because she was wrapped in white linen and forced to fall silent.

Read. Talk. Celebrate your personal library—go ahead and share it. You might connect a reader with a book that saves her life.

You are just one person, but so was Gutenberg, and look what he accomplished.

Enchanted Living is a quarterly print magazine that celebrates all things enchanted.

Enchanted Living is a quarterly print magazine that celebrates all things enchanted.