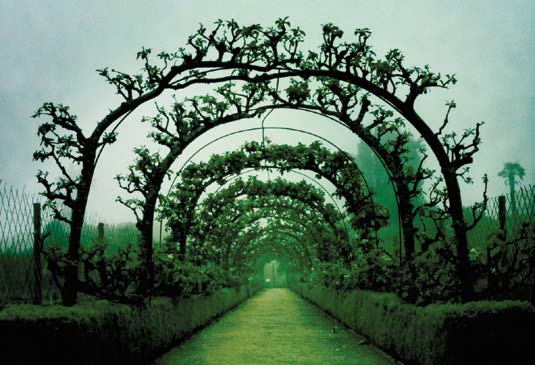

An enchanted forest lies deep in the Cornwall countryside. Surrounding a manor home that was once the country estate of the undisturbed for generations, growing wild and thorny. In 1914, before the Great War, a team of twelve gardeners signed their names under an enchanting but foreboding motto written on the wall of the garden privy: “Don’t come here to sleep or slumber.” Heedless of this warning, the gardens themselves fell asleep for seventy years, under a spell as enchanted as any intended for a Sleeping Beauty. Then one day, two “Prince Charmings” hacked through the vines to discover the mystery hidden in the wild. In 1990, Tremayne descendant John Willis and his friend Tim Smit were exploring the tangled jungles of overgrowth after a hurricane. To their surprise, they came upon a small room buried under masonry and vines. When they read the words written almost a century earlier, they were “fired with a magnificent obsession to bring these once glorious gardens back to life in every sense … The romance of the decay took a hold on [their] imaginations,” as Heligan’s website describes the experience. They banded with a team of enthusiasts and experts and from that point on worked tirelessly to bring the once grand sanctuary back to its former glory.

This was no small task: nature had taken over some areas almost completely. A few of the gardens closer to the estate had been tended by tenants until the 1960s, but some areas had almost seven decades-worth of wild growth. Heligan marketing manager Lorna Tremayne describes the state of the grounds: “Brambles over twenty feet high invaded the derelict glasshouses and self-seeded trees made the Melon Yard almost impassable. Despite this, original features and historic plants still remained within the overgrowth, just waiting to be revealed. In the derelict Head Gardener’s Office a rusty old kettle still hung in the fireplace and in the old Paxton Glasshouse an original pair of vinery scissors remained on a nail on a wall, as if left one day by a gardener expecting to return.”

The restoration process was eventually successful, and had the added benefit of stimulating the local economy. Today, the Lost Gardens of Heligan boast numerous themed gardens, including summer houses, a crystal grotto, an Italian garden, bee boles, a wishing well, and the only remaining functional pineapple pit in all of Europe. The staff of Heligan work to preserve not only the gardens and natural ecology, but local wildlife and rare species as well. A tearoom serves food and teas grown right outside. And when the pineapple pit produces a rare and exquisite specimen of the fruit, both the workers and those lucky visitors who happen to be on hand can taste the bounty. The same is true of the honey production from the bees. The sweet nectar is for sale, but once it’s gone, it does not reappear until the following year.

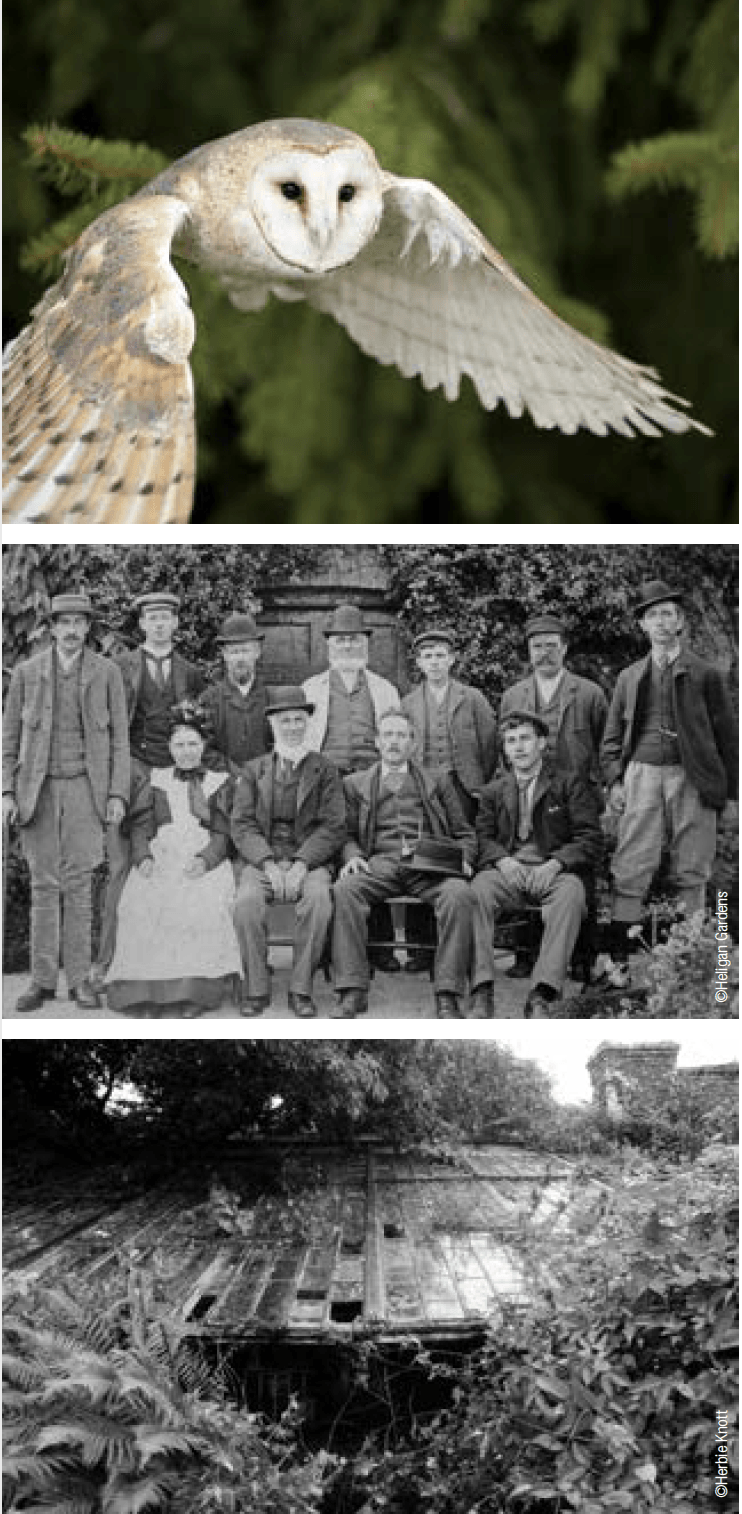

More than bees call Heligan home. Throughout the farmland, woodlands, wetlands, formal gardens, and subtropical jungle, numerous species find their perfect habitat. Owls, otters, deer, bats, foxes, badgers, and all types of birds and bugs can all be found by the watchful observer’s eye. And since the wildlife is so accustomed to people, visitors may even have an up-close encounter. Heligan’s wildlife program is called “Heligan Wild,” and the program transmits a feed from the animal shelter, or “Hide,” built into the center of the estate to its website and Facebook pages, as well as to visitors on-site who might want a non-intrusive way to see what’s going on. This is especially captivating when the cameras capture footage of Heligan’s more elusive, nocturnal creatures.

Barn owls are among the nocturnal creatures that populate Heligan, and staff wildlife experts manage the grounds in a way to increase their safety and protection. A protected species now in decline because of rural development and modern farming techniques, the owls can find nesting boxes and a steady diet of mice and voles thanks to the grassy areas Heligan employees leave wild in order to assist in the dinner hunt. Heligan’s hard work has been rewarded: the owls have now been nesting there for ten years, and generation after generation of small broods of healthy chicks have grown and thrived. In winter, one still might catch a glimpse of a beautiful kingfisher hunting over the lakes in the Lost Valley, and at the Hide one might see a usually secretive wading bird, the Water rail.

For the gardeners of Heligan, wildlife and the plants they tend interact in charming ways. One day Lorna stopped to chat with gardener Mary, “admiring her collection of ‘friends’ watching her methodically weeding the flower bed; namely a robin and two blackbirds. ‘Oh they’re not the only ones,’ said Mary. Casually lifting a foxglove leaf only inches from her hand, Mary revealed a small common lizard that was also waiting in the wings for the fruits of her labor.”

The garden today seeks to heal its human visitors as well as its creatures. Lorna explains how the gardens have a magical effect on people. “It’s certainly no coincidence that the majority of our visitors say that they leave feeling inspired, peaceful, and uplifted. It’s also worth mentioning that Heligan is an anagram of ‘healing.’ The healing influence of the gardens and estate is something that many people return to Heligan year after year to absorb, as if on some personal pilgrimage for the gardens’ restorative powers. Maybe that’s simply the healing power of nature at its best.”

Three signature figural statues are scattered around the grounds, commissioned works of organic art by local artists Sue and Pete Hill. The Giant’s Head, created from the root ball of a fallen tree, represents the whimsy and quirk of Heligan with its rare jungle plants around one corner and rare Tamworth pigs or an emu* around the next. The Mud Maid is another recognized symbol of the gardens. Sculpted of dirt and moss, she reclines on her side in slumber. In each season she changes. She’s become symbolic of the sleeping beauty element of the gardens’ history, and continues to enchant all those who see her. The Grey Lady, a newer addition to the Woodland Walk, is a literal interpretation of the ghost of a “grey lady” who is said to walk the pathway from the big house to disappear among the trees.

Heligan has been awoken from its slumber of almost a hundred years. Those who manage the grounds today maintain it as “a place of inspiration and beauty, where man’s relationship with the land and its inhabitants continues to be explored.” It’s a place that both maintains and sustains lost practices, horticultural methods, and a plant collection, while simultaneously exploring new ideas and technologies to better the hundred acres of land in the future. Heligan has an enormous heart, and enormous goals, but it’s also filled with small and quiet moments of enchanted interaction. As cofounder of the modern gardens Tim Smit so perfectly says, “Heligan is so much more than just a garden—it is a place in the soul.”

*Yes, an emu! Heligan keeps emus today in homage to the Tremayne family’s Victorian tradition of keeping a variety of exotic creatures, including monkeys and emus.

Article from Issue #31 The Midsummer Night’s Dream SUMMER 2015

Subscribe // Order Back Issues