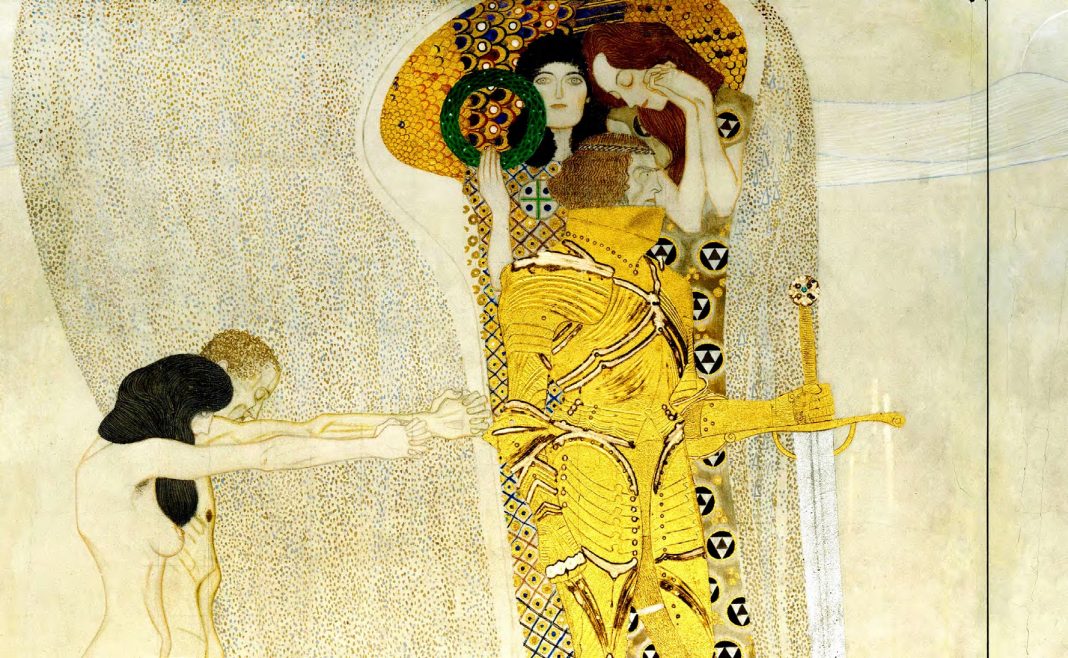

Feature Image: FineArt : Alamy Stock Photo

Imagine what it would be like coming of age in the glittering artistic hotbed of turn-of-the-20th-century Vienna. Gustav Klimt was painting exquisite golden nudes while his lover and sister-in-law, Emilie Flöge, was designing radical new fashions that left the corset and bustle behind. Freud was inventing psychoanalysis and Gustav Mahler was composing monumental symphonies. Art had become the religion of this newly secular age, and artists were worshipped as cultural heroes and saviors.

In this midst of this cultural whirlwind lived an unusually gifted young woman, Alma Maria Schindler. She grew up surrounded by artists and intellectuals. Her father, Emil Schindler, who died when she was thirteen, was one of Austria’s foremost landscape painters. Her mother, Sophie Bergen Schindler Moll, was an opera singer. Her stepfather, Carl Moll, was a painter and founder of the Secession Art Movement. His friend and colleague Klimt gave Alma her first kiss when she was just a teenager.

Living among such luminaries, how could Alma not dream of becoming an artist herself? A new era of opportunity was opening for women, the old rules being written anew. Alma attended concerts, operas, plays, and art exhibitions several times in any given week. Though lacking in a formal education, she devoured philosophy books and avant-garde literature. She was a most accomplished pianist; her teacher thought she was good enough to study at Vienna Conservatory.

However, Alma did not aspire to a career of public performance. Instead, most ambitiously of all, she yearned to be a composer. Her lieder, composed under the guidance of her mentor and lover, Alexander von Zemlinsky, are arresting, emotional, and highly original. They plunge you straight into the zeitgeist of turn-of-the-century Vienna. We know from her diaries that Alma composed more than a hundred lieder. She also composed various instrumental pieces and the beginning of an opera.

But as a creative woman, Alma did not have an easy time. From the very beginning, she saw her sex as a major hindrance. I think it’s very hard for us today to understand the enormous misogyny women faced if they deviated from the traditional feminine life script. Women who strived for a livelihood in the arts were mocked as the “third sex,” as though they were unnatural, deviant, a gender apart from normal women. This was the fate of Alma’s friend, the sculptor Ilse Conrat, who exhibited in the Vienna Secession Museum alongside Klimt and earned her own livelihood but was mocked as a plain spinster. She’s hardly remembered today. Where Alma did receive praise and validation was in the salon, where she was celebrated as the most beautiful girl in Vienna. But those who were drawn to her beauty often didn’t look deeper than the surface. As a result, she felt that she had two separate souls that were constantly at war with each other.

This inner battle came to a head in November 1901, when she met Gustav Mahler at a dinner party. Nearly twenty years her senior, Mahler fell in love with her, literally overnight, according to a poem he wrote for Alma. He proposed only a few weeks later. But his demand that she give up her own composing career as a condition for their marriage plunged her deep into turmoil. Torn by her love and in awe of his genius, she reluctantly consented.

lma wrote in her diary, “I have two souls: I know it. And am I a liar? When he looks at me so happily … what a profound feeling of ecstasy. Is that a lie too? No, no I must cast out my other soul. The one which has so far ruled must be banished.” Born in an era that struggled to recognize women as full-fledged human beings, Alma experienced a fundamental split in her psyche—the rift between herself as a distinct creative individual and herself as an object of male desire. To win Mahler’s love, she sacrificed her creative soul.

Despite this inner loss, Alma and Gustav enjoyed some very happy years together. As his devoted muse, she critiqued his work, copied his scores for him, and stood by his side through good times and bad. They had two beautiful daughters.

Yet underneath it all, Alma was still that questing young woman who yearned to compose symphonies and operas. The suppression of her true self to become the woman her husband wanted her to be was unsustainable and inhuman. Eventually, the authentic Alma erupted out of this false persona.

In 1910, Alma retreated to an alpine sanatorium to recover from a miscarriage and an emotional breakdown. The progressive doctor who ran the clinic prescribed an unusual form of therapy to draw Alma out of her depression—afternoon tea dances. Her dancing partner was a tall and handsome twenty-seven-year-old architect named Walter Gropius. He seemed as drawn to her intellect as he was to her beauty. The two of them embarked on a headlong affair, which unleashed an alchemical transformation inside Alma. It wasn’t simply a case of her rejecting her aging husband to take a virile young lover. I believe she was retrieving her lost creative soul.

What emerged was a free-spoken woman far ahead of her time, who rejected the shackles of condoned feminine behavior and insisted on her independence and her sexual and creative freedom.

When Gustav discovered the affair, he wooed her back by encouraging her to compose again. Alma went on to publish fourteen of her songs. Three of her other lieder have been discovered posthumously. Now her work is regularly performed and recorded.

After Gustav’s death in 1911, Alma truly unleashed her wild side and fell passionately in love with another younger man, the artist Oskar Kokoschka, who immortalized her in his painting Bride of the Wind. But when he grew too possessive and controlling, she broke up with him and married her ex-flame Gropius, whom she later divorced in order to marry poet and novelist Franz Werfel.

Ultimately none of these men could claim to possess her because she was stubbornly her own woman to the last.

Like unconventional women throughout history, Alma to this day faces a backlash of misinterpretation and outright condemnation. She was complex, transgressive, ambitious, and often perplexing.

Alma was neither a “good” woman nor a “bad” woman, but a woman who insisted on being fully human, whatever the price. She was not any one color, dark or light. She was the whole spectrum. So it is with all of us. Every woman contains the totality, the heights and the depths.

This is what drew me to write a novel about her—Alma deserves to be the center of her own story, not just a footnote in the lives of her famous husbands and lovers. She was so much more than a muse or femme fatale. Alma was not only a composer but what in German is called a Lebenskünstlerin, or life artist—she pioneered new ways of being as a woman that was in itself a work of art.

What an inspiring woman.

Love this and all the things it has