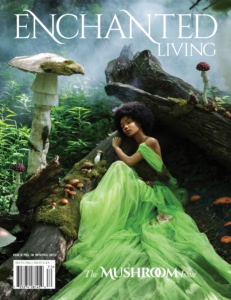

Photography: JOVANA RIKALO @jovanarikalo

Model: Phoebe @phoebymontari

Mushrooms: Ana Youkhana @ana_youkhana

Decor: Tandrbal @tandrbal

Readers of this journal are certainly familiar with the various flower fairies of Great Britain and Ireland, which have been written about extensively in academic journals as well as children’s books. More recently, fairyologists have focused on the flower fairies of the North American continent, such as the Lupine Fairy, the Bee Balm Fairy, and the Joe-Pye Weed Fairy. Although less popular with the public, our native tree and shrub fairies, such as the Dogwood, Redbud, and Buttonbush Fairies, have also been subjects of scholarly attention. However, almost no attention has been paid to what may be the most interesting and elusive fairies of all—the mushroom variety.

Noticing this lacuna, the editor of this journal, Professor Ebenezer Brown, graciously invited me to write about mushroom fairies for my fellow fairyologists. It has been my pleasure to study the Mushroom Fairy (Fata fungi) for the past decade, ever since I completed a Ph.D. in Fairy Studies at Harrington-Hall University in Massachusetts.

At first, my advisor tried to dissuade me from studying mushroom fairies, telling me the topic was simply too obscure. “Why don’t you choose one of the tree fairies that are still under-researched, such as the Spruce or Sycamore Fairy?”

he asked me. He even urged me to consider the nascent field of moss fairies.

“But all of these fairies are already the subjects of established scholarly research,” I told him. I wanted to study something no one had studied before. And ever since I was a child, foraging in the forests of western Massachusetts with my grandmother, I have loved mushrooms, from the common turkey tail (Trametes versicolor) that grows along rotting logs to the resplendent and deadly fly agaric (Amanita muscaria), its crimson cap spotted with small white dots like a sign clearly indicating “Do not touch!”

Seeing that he could not dissuade me, Professor Brown reluctantly agreed to supervise my dissertation, The Varieties of North American Mushroom Fairies, which will soon be published as a scholarly monograph available from Harrington-Hall University Press. What follows is an excerpt from the introduction.

There are many different kinds of mushrooms all over the world, and therefore many different kinds of mushroom fairies. The term mushroom fairy can be used for the entire

family, including for the fairies of toadstools, which are simply poisonous mushrooms. However, it is more accurate to call these fairies by their specific names, such as the Inkcap Fairy or the Common Puffball Fairy. Of course, fairyologists prefer to use the even more specific Latin genus and species designations, so the Hen of the Woods Fairy (also called the Maitake Fairy) is Fata Grifola frondosa.

In North America alone, there are so many mushroom varieties that it would take a lifetime to study them all, and wherever you find mushrooms, from the California hills to the forests of Maine and the Louisiana bayous, you will find their fairies. Just like the flower and tree fairies you are probably familiar with in your own garden, the mushroom fairies guard and care for their mushrooms in various ways. For example, the Morel Fairies wash out the distinctive honeycomb-shaped sacks of the morels with rainwater and tend to any injuries caused by weather or depredation. They protect their mushrooms from the beetles that seem to love them so, although they cannot do much against the deer and grouse that are equally fans of the delicious morels. When I tell you that there are more than fifty different species of Morchella, the true morels, you can imagine how many different kinds of fairies must tend to this one genus of mushroom alone.

The fairies of poisonous mushrooms are even more proactive, and if you are out sketching or photographing mushrooms, you must watch out for their darts or arrows. Although these are small, approximately the size of an acacia thorn, they can be quite dangerous, and if you are stung by them, I recommend an immediate visit to your local poison control center.

Naturally, mushroom fairies have evolved to resemble the fungi they live among, so the Black Trumpet Fairies blend right in to the dark patches of those mushrooms on the forest floor, and the Saffron Milk Cap Fairies stand out as brilliantly orange, unless they are in a group of their mushrooms, in which case they are almost indistinguishable. While flower fairies’ clothing is generally made of petals, and tree fairies’ clothing is sewn from leaves or soft bark, mushroom fairies make themselves outfits using their mushrooms. Their garments can look like anything from the white frills of the shaggy mane, which resemble the fringe of a 1920s flapper, to the wrinkled brown leather of wood ear or the purple velvet of the violet wellcap.

Mushroom fairies also seem to take their personalities from their mushrooms. For example, the Chicken of the Woods Fairies are outgoing and gregarious, while the Chanterelle Fairies are opinionated and as peppery as their mushrooms are reputed to taste. The Hedgehog Mushroom Fairies are earthy and practical, rather like hobbits. The Porcini Fairies are brave, even heroic, in defense of their mushrooms. The Yellow Blusher Fairies are so shy that you will rarely see them. I have seen them only once, and they do indeed blush as yellow as their mushrooms. The Old Man of the Woods Fairies in fact resemble wrinkled grandfathers, while the Pettycoat Mottlegill Fairies look and sound exactly like little girls in pinafores.

Once again I should warn you about the more dangerous varieties of mushrooms, whose fairies are equally so. You must watch out in particular for the death cap, whose fairies look so friendly and unassuming—they will smile at you as they shoot poisonous darts into your hand. The Destroying Angel Fairies are easily spotted by their distinctive white robes and wings, which however are purely decorative. (Unlike flower and tree fairies, mushroom fairies do not have wings or fly, which may be connected to the mushroom’s method of reproduction by spores rather than pollen.) You will know the Funeral Bell Fairies by the tolling of the bells they carry. I have already mentioned the fly agaric, whose fairies are easy to identify by their attractive red dresses with white polka dots.

There is still much we do not know about mushroom fairies. They can be male, female, or neither, depending on the type of mushroom. Regardless of their appearance, they seem to reproduce along with their mushrooms, so if you grow mushrooms, you are guaranteed to have mushroom fairies as well. Thoughtful fungus farmers (who grow mushrooms, yeasts, and molds) will provide water and shelter for the fairies that guard their mushrooms, knowing that the mushrooms will be healthier with fairies to care for them. However, if you wish to retain fairies for your mushrooms, you must use organic methods, because fairies will not stand for insecticides of any kind and will leave your farm directly if you use them.

If you wish to communicate with a mushroom fairy, I suggest you find one of the more sociable mushroom species, such as honey or oyster mushrooms, or even puffballs, although their fairies can be unpredictable. If you approach the fairies of whichever mushroom species you have chosen very politely, they may sit beside their mushrooms and have a conversation with you. I myself have been fortunate to gain the friendship of a Greenspot Milkcap Fairy who has told me a great deal about the secret life of the forest, to which humans are not usually privy. But the mushroom fairies see it all: the slow growth of trees over many seasons; the spring birth, summer blossoming, and autumn decay of flowers; the brief, vivid sojourn of foxes and owls and chipmunks. She has also

told me about the lives of the mushrooms. Did you know there is much more of a mushroom under the ground than above? And did you know that through an underground network, mushrooms communicate with trees and enable them to communicate with one another? My Greenspot Milkcap Fairy has shown me how everything we see in the forest is connected, like a great web. We have sat together for hours on a mossy bank, me in my jeans and flannel shirt, she in a rippling green robe resembling the green cap of her mushroom, listening to the sounds of the forest around us. Sitting there, it seemed to me that I learned the great secret of the forest, which is patience.

There is still so much work to be done in the field of mushroom fairy scholarship. I urge my fellow fairyologists to study these important fungal spirits. Without them, how would the mushrooms grow? And without the mushrooms, how would the forests and our other natural ecosystems thrive? Graduate students in particular should focus on the fairies of lesser known mushrooms such as the shaggy rose goblet, which looks like a scarlet cup; the dog’s nose mushroom, which looks exactly how it sounds; the sulfurous staghorn jelly; the milky, globular shooting star; or the fluted bird’s nest, which seems to contain small white eggs. There are so many mushrooms and their fairies still to study! By searching for these species in the forests and fields and deserts where they are found, researchers will add important scholarship to the field of fairyology and teach us more about the fascinating Mushroom Fairy.