Feature Image: Fairy Resting on a Mushroom (1860), by Thomas Heatherley

The house we lived in when I was a child had a storage cupboard outside the front door. Possibly inadvisably, my father grew mushrooms in there, making the cool, dark, tiled space smell earthy and magical. Outside, our modern home bordered a wood rich with puffballs, ink caps, and all manner of strangely named fungi.

I always knew that the mushrooms in the cupboard were safe, but it was best not to touch the ones in the wood. As a little girl, I did not understand why; I was too young to tell the poisonous from the delicious, so I rationalized that those mushrooms in the woods were homes to fairies or pixies and that it would have been rude, not to mention risky, to disturb them.

I was being unexpectedly Victorian in my reasoning, as the 19th century love of mushrooms was science tinged with fairy folk. The growing interest in vegetarianism in the latter half of the century celebrated the “meaty” delights of some of the larger specimens, while the button mushroom was a little gem to be added to stews.

And with more and more lady artists casting about and searching for suitable subjects for their still-life paintings, it seems unsurprising that they’d be attracted to the smooth white caps, velvet gills, and pops of color that marked the different varieties of fungi. And still-life pictures of nature were considered safe and appropriate.

Not only the mushrooms themselves but the genteel peasants who gathered them became the subject of works of art. In The Mushroom Gatherers (1878), James Clarke Hook showed a girl holding a wide basket full of fungi, her little brother on the ground in front of her pulling up a particularly large specimen. Similarly, in James J. Edgar’s The Mushroom Gatherer (c. 1860s), a beautiful young woman in modest working clothes sits beside her equally beautiful basket of shrooms, all pale and ripe like their collector.

These girls might have been particularly fond of foraging because of its perceived link to witchcraft. In Valentine Prinsep’s Medea the Sorceress (1880), the beautiful witch gathers red-tipped toadstools and places them in her basket, no doubt to fuel her craft rather than her breakfast. Of course she’s gathering the Amanita muscaria, or fly agaric, possibly the best known toadstool, renowned for its narcotic effect. For the Victorians, the red top with its white flecks symbolized positive magic as well as mischief and was even believed to have inspired the robes of Father Christmas (although I’m sure a certain cola company would have something to say about that). Broken into little pieces and soaked in milk, the fly agaric provided a powerful and irresistible poison to flies, and, when dried and swallowed whole, would inspire wild dancing and the spilling of secrets.

The botanist Mordecai Cubitt Cooke published a ten-volume guide to British fungi and wrote extensively about hallucinogenic plants and the mind-altering effects of the fly agaric shroom.

This stunner was also well-known as an antidote to nightshade poisoning, so Medea’s gathering might have been medicinal rather than murderous.

I’ve always wondered what the difference between a mushroom and a toadstool was and the answer is danger.

While there are stipulations that a toadstool has a stalk and a cap, we can all think of innocent white mushrooms that fit the definition but would never be called toadstools. During outbreaks of poisonings such as the epidemic in New York in 1893, the poisoning of the Marchant family in England in 1891, or the Andrieux family in Mureaux, France, in 1882, the perils of toadstools were always blamed. During the latter case, newspapers warned quite dramatically of “the danger of mistaking toadstools for mushrooms.” Quite honestly, all toadstools are mushrooms, but not all mushrooms are toadstools. The very word toadstool is a warning.

It also tells you there is something magical afoot. Do toads need to sit on stools? The toad in my garden needs to sit grumpily under my lavender bush and has never once expressed a desire for furniture.

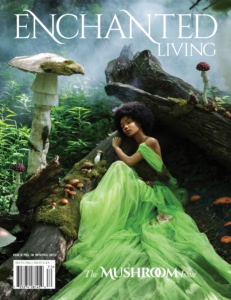

Of course, where there are toads, other magical creatures usually abound. An interesting example is in John Anster Fitzgerald’s The Intruder (1865; pictured on page 38). The artist had such an obsession with the miniature magical world, he became known as Fairy Fitzgerald and was described by the London Daily Chronicle as “the well-known painter of hob- goblins, fairies, imaginative and classical subjects and portraits.” In The Intruder, wee fae folk confront a toad who wants to access his stool. The situation appears to have escalated fairly quickly with fairies of all sizes getting involved, yet the toad looks completely unbothered by it all—which is very brave because some of those little sprites look terrifying. More sensuous are the fairies of Thomas Heatherley (see page 71), their pink curvy bottoms and flaxen hair spilling over the white flesh of the mushroom cap. These are saucy fairies perched on pearly fungi, perfect and glittering, unconcerned with the matters of man.

There are often accompanying pointy-hatted pixies, mind you, fighting with snails, which is enough to entertain anyone.

As a complete contrast, the fairy ring mushroom, Marasmius oreades, brings such positivity that poet Eliza Cook wrote a whole ode to its glory. Her poem contains the repeated refrain “For, while love is a fairy spirit, / The world is a fairy ring.” While the toadstool seems to shun human interaction and keep company with some very unpleasant types, the fairy ring of mushrooms invites the human in to meet the fae. In Edward Robert Hughes’s Midsummer Eve (c. 1905) a girl stands amid a full fairy ring and jamboree with lots of tiny fairy lights and naked fairies, as one does.

Little Victorian girls seem to have had a particular affinity with mushrooms, seen especially in Edward Atkinson Hornel’s works The Little Mushroom Gatherers (1902) and Gathering Mushrooms (1930) and Florence Small’s The Mushroom Girl (1886). These girls are dressed in picturesque rural attire, with spotless aprons and little baskets and not a dirty fingernail among them. I wonder if the link between young girls and mushrooms is that their innocence chimes with the fae sprites that find them. That’s why it seems perfectly natural that, in the 1917 case of the Cottingley Fairies, it was young Elsie Wright and Frances Griffiths who saw the fairies rather than their parents.

If human interaction with fairies and their rings seems to cause trouble, then far more civilized is Walter Jenks Morgan’s A Fairy Ring (1870–80; pictured on page 5). Here we have a very demure circle of fairies, both male and female, fully dressed and listening politely to the fairy who’s speaking. Maybe it’s the presence of humans that makes fairies behave wildly—do we lead fairies astray? I always thought it was meant to be the other way around, but upon further reflection, we humans are a rum lot. Morgan’s fairies obviously conduct themselves in a democratic manner—dressed, neat, free of fighting or debauchery. The pale mushrooms reveal white gills beneath, giving the impression of purity, refinement, and goodness.

These fairies and their mushrooms are positive forces in the world, but that world is not ours.

In the end, the problem with mushrooms may be that they’re not primarily made for humans. Mushrooms in all their guises are unexpectedly beautiful things, so it’s not surprising that people believed them capable of all manner of magic and, by extension, mischief and malice. I was surprised to find that the fly agaric—arguably the archetypal forest mushroom—is in fact a rare sight in Britain’s woodlands. Its dangerous red coat announces that particular toadstool’s poison, unlike some of

its more innocuous, pale cousins native to Britain’s woods. The destroying angel (Amanita verna) and death cap (Amanita phalloides) look very similar to the ones I have lined up for my risotto tonight, as it happens, all pearly white and innocent.

I ought to reassure you that as a sensible coward, I foraged mine from my local supermarket. The advice my parents gave me as a child was wise after all: Do not steal the fairy houses for your supper; you might not live long enough to have the leftovers for breakfast.