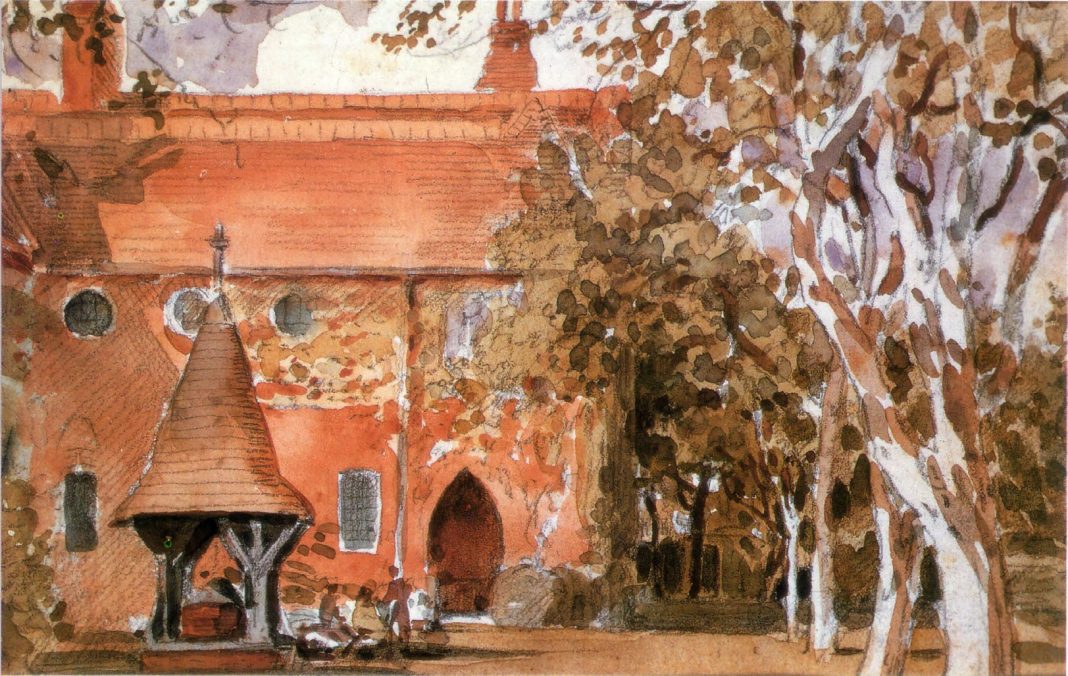

Feature Image: Red House, Bexleyheath painted by Walter Crane. Wikimedia Commons.

Perhaps of all the words ever said by a Pre-Raphaelite, the most frequently repeated are William Morris’s: “Have nothing in your houses that you do not know to be useful, or believe to be beautiful.” In a brotherhood of artists whose name reflected the lofty goal of returning the art world to the beauty it held centuries earlier—before Raphael—and whose members painted subjects as formidable as ancient myths and biblical epics, Morris argued for the importance of the simple concept of home. And this opinion was respected by his peers, in part because he put his money where his mouth was.

Red House was a red brick building commissioned and co-designed by Morris and architect Phillip Webb that was described by Dante Gabriel Rossetti as being “more of a poem than a house.” And in fact, it was designed the way an artist would design a home. Windows were put in where they would let in the most light, not necessarily where they would create symmetry. The actual shapes of the windows were determined more by the purpose of the rooms rather than the impression they would make from outside, and round, rectangular, and square windows dot the exterior. Medieval turrets and Gothic pointed arches above at least some of the windows were a must, and there was a wishing well in the courtyard. It was an outlandish way to design a home, especially in the Victorian era, when draperies and densely packed interiors took higher precendence than the flow of light. Somehow, through the collaboration of Morris and Webb, it all worked beautifully and pleased the eye. And then the Brotherhood moved in.

Morris and his family and friends filled Red House with joy and laughter … and no small amount of creative expression. These were imaginative people who wanted to leave their mark on anything and everything; many a guest entering the home was handed a paintbrush and told to get to work. The ceiling was painted, the walls were painted. The furniture was painted. The stained glass windows were inscribed with Morris’s motto, “Si je puis,” or “if I can.” Other than the Persian rugs and the Delft china, virtually every other item inside Red House was made to order by trusted artisans, to Morris’s specifications, and then decorated by this small but mighty community of artists.

As is so often the case in tales about the Brotherhood, hijinks also ensued. A legendary story tells of a guest (who may or may not have been Rossetti) who snuck around in the night and changed Morris’s previously mentioned motto on at least one of the painted wall scrolls to say “as I can’t” in Latin. A stunning Burne-Jones mural of Morris and Jane Burden Morris as Sir Degrevaunt and Melydor in the drawing room features

a sleeping wombat under a chair. (Thanks to Rossetti’s love of exotic animals, the wombat was a reoccurring image in their visual jokes to one another.) And then there’s the hidden smiley face in the intricately repeating medieval pattern on the stairwell ceiling, tucked into a corner between two wooden rafters. These small signs of reality in an otherwise lofty, magical space help prove that none of these now famous artist friends took themselves too seriously. They were often teased or brought back to reality with love whenever they were tempted to.

Red House was often brimming with beloved guests, and the house itself responded gratefully to such attentions. Descriptions of these heady days tell how the apple trees grew so close to the house during the summer and autumn months that the branches would toss apples into the full-skirted laps of visitors. On one occasion, artist Charles Faulkner hid a small artillery of apples in the built-in gallery and lobbed them at other guests in an all-out war until one hit Morris square in the face, giving him a black eye. Of course all that happened a day or two before Morris was scheduled to give one of his sisters away at her wedding, and the group laughed heartily at the impression his shiner would make. Games of hide and seek were not uncommon, as were boisterous wrestling matches and physical pranks like balancing candlesticks on a door frame to fall on an unsuspecting victim.

Sadly, Morris lived in his dream home for only five years, even though he intended it to be his house for life. Health challenges and the cancellation of plans to share the house with Burne-Jones and his family made his “palace of art” unsustainable. But subsequent owners continued his legacy. The second owner used a Morris wallpaper (by then, his firm was well-established in the home decor field) in Red House, and another 19th century owner began the tradition (carried on for decades by future owners) of asking every guest to his house to scratch their names into panes of the glass wall in the hallway. Notable signatures include May Morris (William’s daughter) and Georgiana Burne-Jones (Edward’s wife). Morris himself never returned to the home, however. He said it would be too emotional a reunion.

Although the story of Morris’s experience at Red House might not have had the fairy-tale ending its exterior evoked, the legacy of those five years spill down through time. The youthful exuberance and artistic flair of Morris and his friends’ Red House years show that a house does not become a home unless it is filled with not only joy and laughter, imperfections and jokes, but also the specific imprint of the people who live there. Favorite quotes written on walls, murals of the owners as their favorite characters from their favorite stories, furniture so perfectly built for the house that it could never be moved away, paintings by artistically minded friends—these ideas are not just the stuffy and antiquated concepts of a Victorian family home. They are rules we can live by in making our own homes thrum and vibrate with enthusiastic energy. They are how we can show our homes we love them and ensure that they love us back.