Fairies are notorious for tricking folks into making bad decisions. (See Shakespeare’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream: transformations, potions, falling in love with jackasses.) So it’s natural that hucksters, peddling their own magic and illusions, would people their ads with pixies. Ever since the Victorian age of advertising, fairies have been waving their wands, casting their spells. Come play, they seem to say, giving us a knowing wink.

But when you look close at the history of ads, it doesn’t actually seem such a perfect marriage of mortals and fairies after all. Fairies prove as tricky in advertising as they do in real life. Advertisers can’t quite pin those butterflies down. Are they pure and innocent? Or are they flirty and dumb? Are they wistfully feminine or raggedly tomboyish?

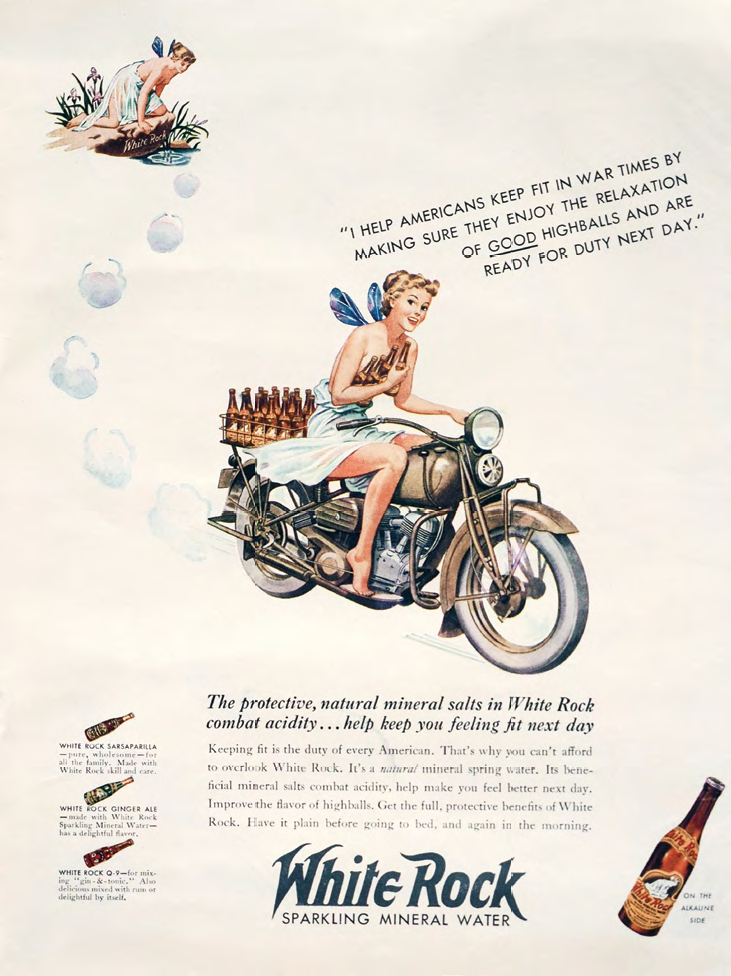

Take a look at the White Rock fairy: sometimes ethereal goddess, sometimes fleet-footed cocktail waitress. In the 1890s, an image of a delicate-winged woman perched on a rock was adopted for the labels of White Rock bottled water; she was based on a painting of Psyche (of Greek mythology) by Paul Thumann. To the company, she represented the water’s claim to purity and natural healing.

Flash ahead to the middle of the 20th century: The White Rock fairy now posed as a post–World War II sex pixie. The cocktail hour was an effort to restore order in the newly topsy-turvy USA, the men home from war and ready to assume a casual authority that the women weren’t necessarily ready to relinquish. So magazine ads pushed White Rock as a healthful mixer, with the topless fairy pouring us a drink. One ad featured her fluttering along on her flimsy wings and clutching an armload of bottles to her naked chest.

“I see to it that you enjoy your highballs tonight,” she promises, “and feel fit for your work tomorrow.”

Meanwhile, other fairies of the postwar era were pitching their goods to women, not with sex appeal but with the taps of their wands. An ad promoting dextrose features a fairy magically producing a strawberry cake; in an ad for a bath scale, a fairy touches her wand to the number on the dial. Yes, take it from the fairies, you dutiful wives of the 1950s—you can have your cake, eat it too, and not gain a pound.

But in the Victorian era, the fairies of advertising tended to be cherubic and teensy-weensy, wearing flower blossoms for bonnets and astride butterflies and other insects. This motif was central to an 1899 magazine ad for Fairbank’s Fairy Soap. Often promoted as “pure, white, floating,” a bar of Fairy Soap was carried through the woods by naked, baby fairies who, despite being winged themselves (and with antennae), ride a team of bees.

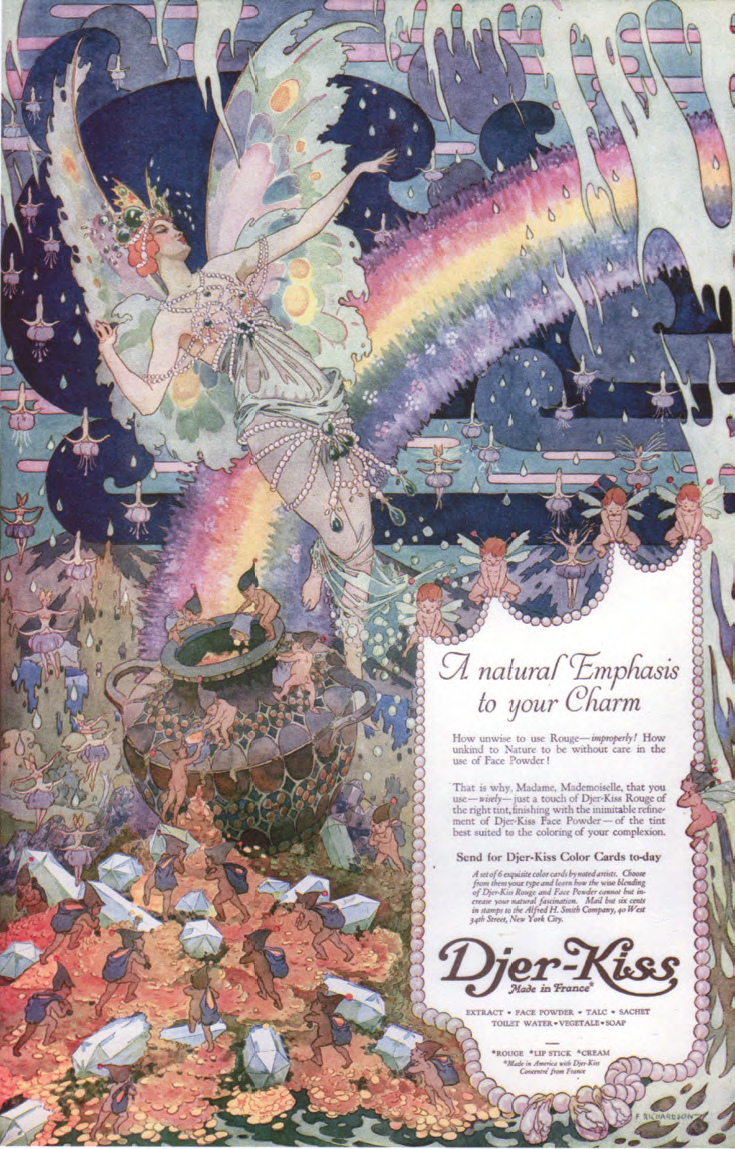

By the 1920s, these little bugs had grown into ethereal beauties. One of the most famous fairy-inspired ads is for Blue Moon silk stockings, featuring a flapper with a head of golden curls, sitting in the scoop of a crescent moon, her negligee fluttering out from her back like silk wings. And Djer-Kiss (pronounced “Dear Kiss”) promoted its perfumes and beauty products with ads and illustrations riddled with fairies, to suggest enchantment and its “so fine, so soft” powders. Printers’ Ink, a magazine for advertisers, wrote in 1920 about the Djer-Kiss ads, which were illustrated by one of the era’s most esteemed artists: “When Maxfield Parrish paints a canvas in color, filled with fairies and goblins and mystic forests, and royal purple hills and magic castles, Djer-Kiss begins slowly to materialize as something more than a scent locked in a bottle.”

It’s actually a great and useful piece of information. I am happy that you just shared this helpful information with us. Please stay us up to date like this. Thank you for sharing.

I like this web site because so much utile stuff on here : D.