It’s an answer, a rallying cry even, to a planet in peril. A relatively new literary and artistic movement born out of speculative fiction, solarpunk is sci-fi on ecstasy, more utopian rather than dystopian, a place of lush, fertile beauty bursting with life that seamlessly unites the technology-driven modern world with the natural one. Owing an indisputable debt to cyberpunk, biopunk, and steampunk, its ethos nonetheless is rooted in environmentalism and the hope that clean energy like solar power represents. It’s got a DIY vibe and is concerned with social justice and climate change, and its aesthetic bears no resemblance to the polluted industrial wasteland that so much of science fiction inhabits.

Instead, solarpunk design often recalls the finest tenets of Art Nouveau, according to author and musician Rosie Albrecht, who edits the solarpunk zine Optopia. “In my understanding, Art Nouveau became a part of solarpunk simply because the aesthetic of Art Nouveau is all about incorporating organic designs,” she says. “There’s nothing artificial about it. It’s a colorful aesthetic ripe with flowers, vines, branches, reeds, and so on. Even its abstract forms tend to have soft, curving lines. It’s an aesthetic that strays away from sharp corners and straight edges, which is a clear marker of human artificiality.”

It’s not merely an appeal to the natural world, though. “I think there’s something about the ornamentalism of it all that’s really appealing to solarpunks,” Albrecht says. “One of the things that makes our current society so sad and drab is that everything these days is built either for efficiency or pure excess. Art Nouveau makes things beautiful just for beauty’s sake, in a way that’s accessible to everyone, not just the rich. One of the most iconic pieces of Art Nouveau architecture is the Paris Métropolitain station—and public transit is super solarpunk.”

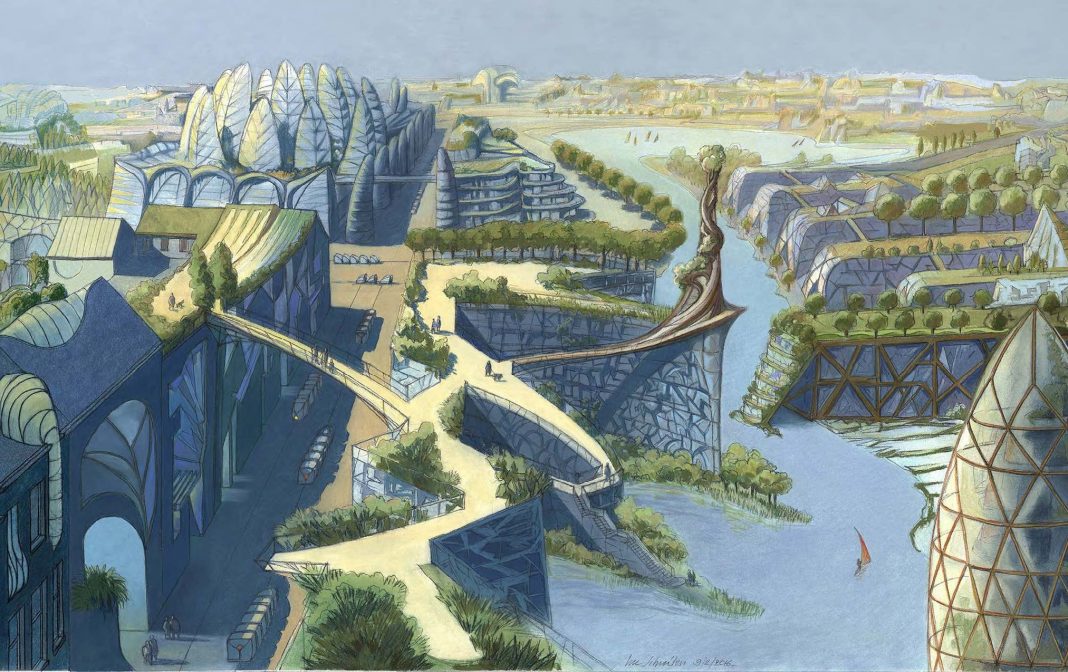

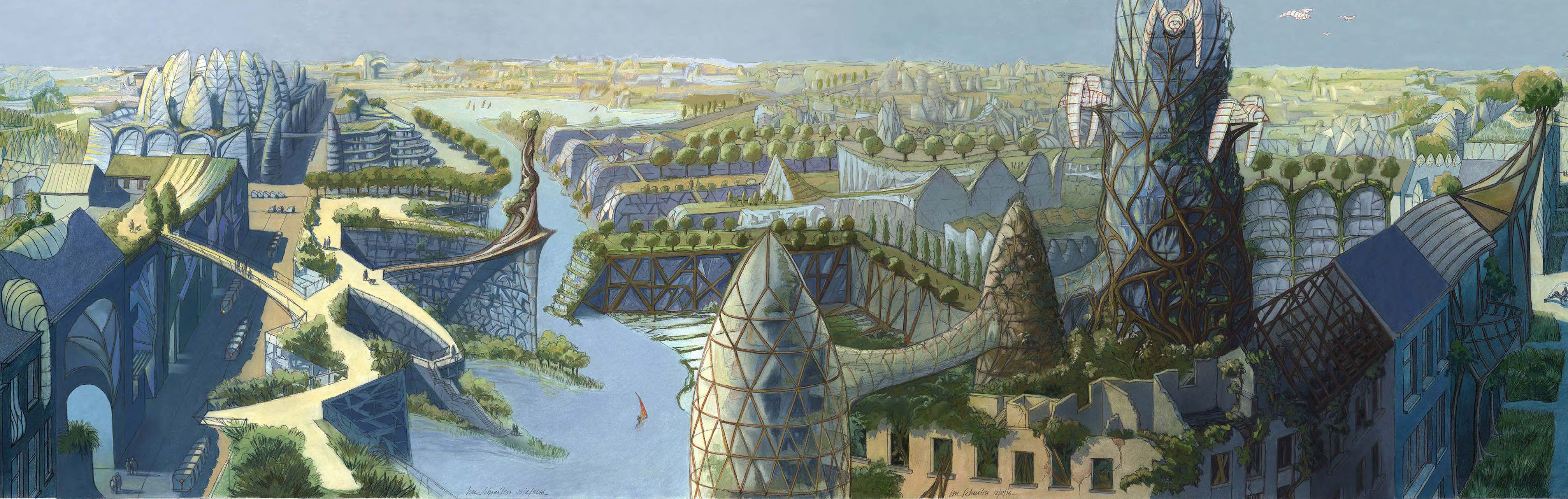

So too is the work of Luc Schuiten, a Belgian architect whose visionary designs like Vegetal City anticipated the movement. Schuiten coined the term archiborescence, a kind of architecture that uses living substances like trees and plants as building materials. When he writes of what inspired him to create Vegetal City, he could have been penning a solarpunk primer: “To break with everything you know and to conceive a dream of somewhere else, of a different way of living—it’s one of the most fascinating intellectual ideas you can examine. That’s what’s behind this work. In addition, it uses the theoretical and technical concepts we already have and combines them with the attitudes toward development which are best suited to the realities and necessities of our life on Earth … Free from all the constraints imposed by capitalism, this far-sighted vision of our environment considers our various ways of life against a background of sustainable development.”

Schuiten’s designs, which share much with Art Nouveau, imagine a brighter future marked by sustainability, peace, and prosperity rather than the overwrought consumerism, greed, and plundering of natural resources that are the hallmarks of industrialization. It acknowledges the current model is no longer feasible, but rather than offering up mere pessimism, Schuiten’s work, like solarpunk, shows us a way forward. There is a graceful sunniness to it, both literally and figuratively, that solarpunk—and Art Nouveau—also share.

“As a historian of solar architecture, what I find wonderful about the solarpunk movement is its optimism and its sense of community,” says Anthony Denzer, head of the department of civil and architectural engineering at the University of Wyoming. “There’s a big corporate influence and hard-nosed pragmatism in the green building and alternative-energy communities, so it’s a breath of fresh air to have solarpunks imagining a different future.”

And their aesthetic roots are beginning to show. “For a long time the Art Nouveau influence has been dormant,” Denzer says. “But now solarpunk artists and designers are embracing that influence, and to me it feels right because we need a new language of architecture which expresses new values. It seems to me that many solarpunks are envisioning buildings as organisms rather than machines, and that strikes a deep chord.”

The concept of solarpunk can be traced back to 1960s science fiction and the work of counterculture figures from that decade, like Peter van Dresser, Steve Baer, Mike Reynolds, and the New Alchemists. But the actual word solarpunk didn’t surface until around 2012. Both the term and the movement have been spreading quickly since then, appearing in articles in publications from around the world, on social networking sites including Pinterest, Facebook, and Reddit, and even in literary anthologies such as Sunvault Stories of Solarpunk and Eco-speculation. That’s all good news, because according to Albrecht, solarpunk just might save us all.

“Solarpunk is important because it’s not just a utopia. It’s a vision of a future that could actually exist,” she says. “We have all the technology necessary to create a solarpunk world. We already have green energy, sustainable farming methods, vertical farms, compostible materials, and so much more. All we need to do is implement it. If enough people are inspired by such a beautiful vision of that future, perhaps we might be able to make it a reality.”

Visit Optopia at optopia-zine.tumblr.com; find Anthony Denzer at solarhousehistory.com and Luc Schuiten at vegetalcity.net/en/.