Picture the heavenly death of lab rats subjected to absinthe tests, like those reported in the Boston Medical and Surgical Journal of 1894: “The guinea-pigs utilized by Cadéac and Albin Menuier in studying the action of the vapor of the essence of hyssop, were victims of the incense of this poetic and biblical plant.”

Are you seeing the critters in an absinthe den, indulging properly? A glass urn, riddled with spigots, pulses slow drops of water, leaky-faucet-style, onto a sugar cube. The sugar is perched on a slotted spoon, the spoon straddling a cocktail glass with a splash of absinthe in its cup. If these methods—with their tubes and green tonic, with a touch of the match to singe the sugar—seem those of an apothecary, you’re not far off: Many of the curatives of the fin de siècle seemed straight from the saloon, with the pharmacist and bartender brothers-in-arms.

Toss into this partnership the local newspaper, which funded its yellow journalism with column after column of advertisements for medicine and liquor both, while also running full-page stories on the perils of the very products it pushed.

“Gullible America will spend this year some seventy-five millions of dollars in the purchase of patent medicines … it will swallow huge quantities of alcohol, an appalling amount of opiates and narcotics … and far in excess of all other ingredients, undiluted fraud.” This comes from The Great American Fraud, an exposé by Samuel Hopkins Adams published in 1905, which led to the first national food and drug laws. The article was particularly focused on Peruna, a popular medicine (and major advertiser) that was at least half “cologne spirits” (the druggist’s term for alcohol), the other half water, with a little cubeb (pepper) for flavor and some burned sugar for color—not far from the absinthe cocktails that the newspapers preached as a deadly habit of the leisurely French.

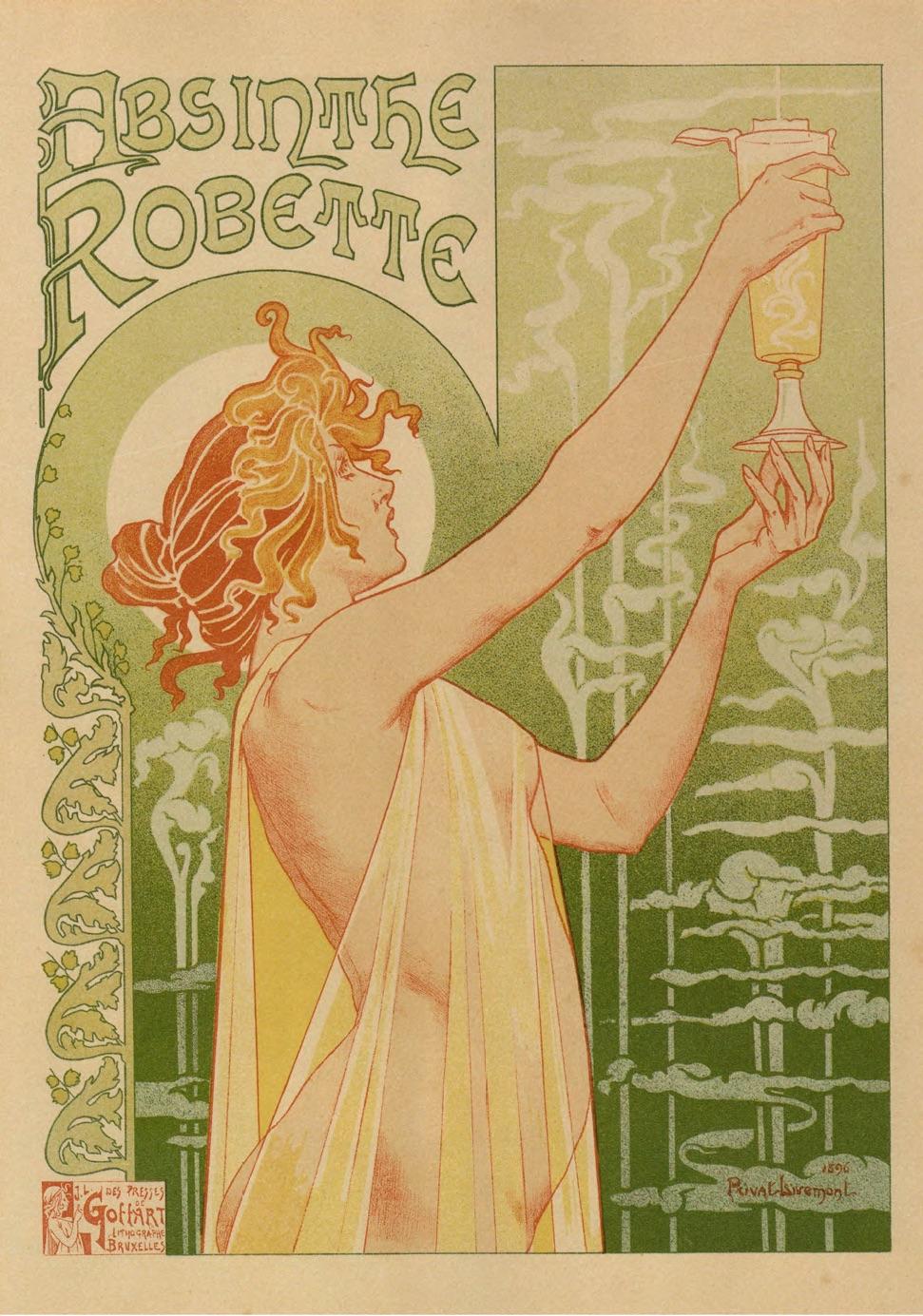

Absinthe was a green terror, a green peril, a green menace, in headline after headline. The Portland Daily Press, in 1897, wrote of absinthe’s “dolphin colors,” and how the drink is like the Frenchman, “perfumed and fragrant like his foppery … bitter like his philosophy … yellow like his morality, and inflaming like his passions.” Some of the articles were accompanied by lush portraiture of the absintheur in the happy throes of hallucination.

It was a golden age of newspaper and magazine illustration, resulting in Art Nouveau imagery that was equal parts fantasy, mortal danger, and seduction. A 1901 edition of the San Francisco Call featured a full-page illustration of a man in his chair with an empty glass and surrounded by delusions, a fairy drilling a hole in his head, a winged elephant on a bird’s perch, a dragon-headed butterfly flitting about. The delight the artist indulged is somewhat reflected even in the article’s giddy cautions: “Society is all agog over the recent discovery that a coterie of girls in a fashionable uptown boarding school have been caught tippling absinthe.” (That uptown “tippling” makes them sound as sated as the guinea pigs mentioned above.)

An 1894 article from The Evening Dispatch of Provo, Utah, warns of absinthe’s treachery, then goes on to give tips on how to best fix it for yourself: “It is the precipitation of these [volatile] oils in water that causes the rich clouding of your glass when the absinthe is poured on the cracked ice—double emblems or warnings of the clouding and the crackling of your brain if you take to it steadily. Thus every drink of the opaline liquid is an object lesson in chemistry that carries its own moral … Some barroom Columbus, ambitious to outdo Dante and add another lower circle to the inferno, recently invented or discovered the absinthe cocktail. A little whisky—the worse the better—a dash of bitters, a little sugar and plenty of iced absinthe make about the quickest and wickedest intoxicant in the world.”

A cocktail guide titled Modern American Drinks (1900) is largely indifferent to the guinea-pig killer and includes many formulas for absinthes, including the Brain-Duster, a cocktail with absinthe, gum syrup, Italian vermouth, and whiskey. As one other turn-of-the-century cocktail guide offers as its epigraph: “Inasmuch as you will do this thing, it is best that you do it intelligently.”

To cocktail intelligently in this age, you’d be expected to keep a bottle of absinthe, along with yellow chartreuse, Apollinaris water, sauterne, crème d’allash, orgeat syrup, Eau de Vie d’Oranges, calisaya, extract of beef, and many egg whites and egg yolks. And according to Modern American Drinks, you’d be mixing “cocktails, cups, crustas, cobblers, coolers, egg-noggs, fixes, fizzes, flips, juleps, lemonades, punches, pousse café,” as well as collins, daisies, frappes, rickeys, smashes, and sours.

The recipe for Burned Brandy (which, we’re told, is “good in a case of diarrhea”) is simple enough: “Put two lumps of cut-loaf sugar in a dish; add one jigger good brandy, and ignite. When sufficiently burnt, serve in a whiskey glass.” Something called Gin and Pine seems a little less so: “Take from the heart of a green pine log two ounces of splinters, steep in a quart bottle Tom gin for twenty-four hours, strain into another bottle. Serve same as straight gin.”

An article in 1904 celebrates a radium cocktail that “glows before taking … Passing is the epoch of the ruby Manhattan, the yellow Martini, the garnet vermouth, the opalescent absinthe, and the old-fashioned whisky cocktail of the sunset tint. The white radium cocktail has come.” The recipe for this Sunshine Cocktail is “one part Alpha (positive); one part Beta (negative); one part Roentgen salt; mix thoroughly and place in glass tube. Put glass tube in cocktail glass of water. Turn out the light. Drink shining.”