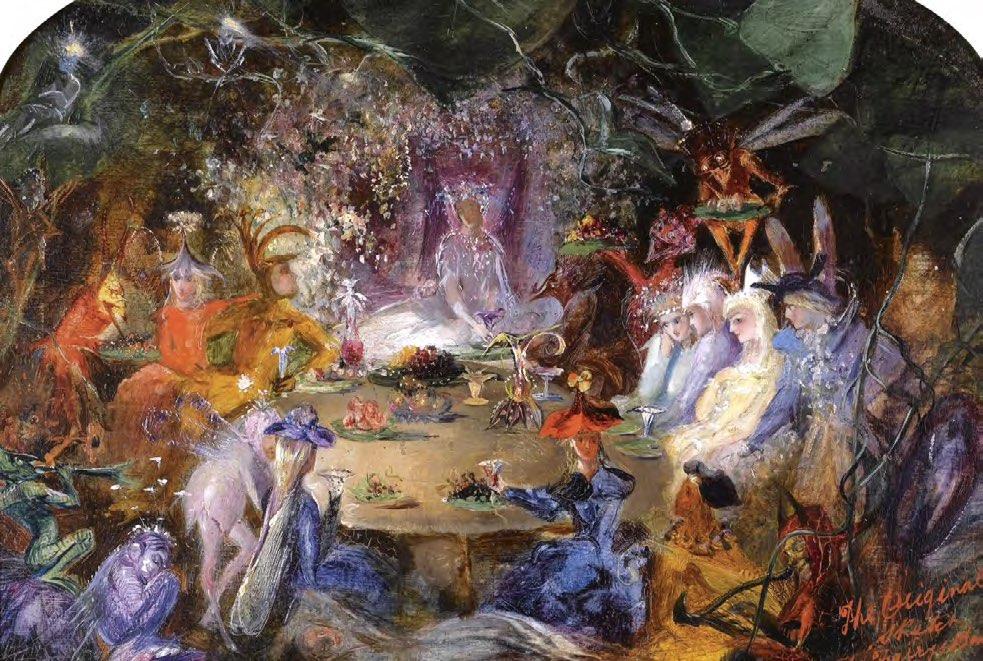

Feature Image: The Fairies’ Banquet by John Anster Fitzgerald. Wikimedia Commons

Magic in the 21st century has undergone many fantastic changes and evolutions, but its most ancient face still appears in a few discreet patterns that hold their shape across time and place. This statement is perhaps one of the oldest shapes of all, the understanding that every cure we seek lies hidden at the root of each curse we endure. I learned this truism at the knee of the storytellers in my own family, grandparents and a great grandmother who told it to me in a hundred different tales and a thousand different ways. And then I learned it in the various magical traditions I trained in, practice, and teach today. This notion that the cure is in the curse is not a rationalization for why you might become ill or why your lover has suddenly up and left. Rather it is an observation often made with a cold eye and in a nonjudgmental manner. It is not about what is right or wrong or easy or hard but a plain fact staring you in the face, if you are willing and able to pay attention. And it has ramifications that shape our stories both on and off the page.

Take the ballad of Tam Lin, a Scottish ballad that dates back to 1549 in written form but deals with motifs and story lines that are much, much older. Tam Lin deals frankly in curses. The core of the tale is straightforward: A young girl (Janet) falls in love with mysterious handsome knight (Tam Lin), discovers that she is pregnant with his child, then discovers he has actually been held (against his will?) by the faerie queen. To free him so that they may live happily ever after, she must pass a test. In this case the test is Tam Lin changing forms from an adder to a toad to a lion, wolf, bear, and piece of hot burning lead. The young girl completes her task admirably and wins the knight back from the faerie queen, who is none too pleased with the events but nevertheless accepts them.

Tam Lin is riddled with curses. This is immediately apparent in the way it is most commonly told in modern times. My paternal grandfather, a staunch Catholic with a good deal of Scottish heritage, first told me the tale of Tam Lin, and he told it to me, I imagine, much as it had been told to him, as a warning not to meddle too much in the business of faeries and not to wander too far into the woods, especially as a young person, and not to draw unwanted attention to oneself. I was struck then, as I am every time I encounter the story anew, by how transgressive the tale is on so many levels, centering on a fiercely independent woman who does the saving instead of becoming the saved. Hanging in the background of the tale is the warning—take care or you too will draw the ire of the faerie queen, take care or you too will feel her curse.

But what is the curse exactly? In the story of Tam Lin, one would be hard pressed to pick just one. Tam Lin the knight is cursed when he draws the attention of the faerie queen and

is taken captive in her court … or is he? The nature of their relationship is unclear, although apparently sexual, and he has been with her a long time—seven years. Janet sees her unborn child as a curse and takes action to rid herself of it as she sees no other alternative. Tam Lin is cursed again as he understands that he is about to be offered up as part of the faerie court’s payment to hell. The lovers are cursed, and Janet must accomplish the most difficult of tasks—remaining constant in the face of violent and unceasing change—to win her beloved back.

And then the story,which climaxes with Janet’s success and Tam Lin’s final transformation back into his rightful shape as a mortal man, ends with a curse uttered by the faerie queen herself:

“But had I kend, Tam Lin,” said she, “What now this night I see,

I wad hae taen out thy twa grey een, And put in twa een o tree.

These words mark the end of most traditional renditions of the ballad and give us a unique kind of curse, a speculative curse perhaps, one that is structured as a syllogism: If I had known then, I would have …

Returning to our opening premise, if there is a possibility of a curse then there is also the possibility of a cure. But what is the ailment here? What is the needed cure?

To answer this we need to go back to the beginnings of the tale, into the woods. For it is here in the woods where Janet first encounters the handsome fae knight while she is doing something very particular: picking roses, double roses to be precise, and “breaking their wands”—i.e., breaking or cutting their stems. Moreover, when Tam Lin appears and asks her why she is doing this, she claims that the land belongs to her.

It is easy to see how the warp and weft are coming together in this particular pattern. Janet is not a bad person; indeed throughout the ballad she is shown to be brave, strong, and somewhat wise. But she is young, untried, and unseasoned in this opening scene. She is selfish. She is claiming ownership of the land and the right to pick the flowers no matter what or whom it may hurt. But the land was understood to have guardians of a much more ancient nature. The land was understood by the people at this time much as it is still understood by indigenous people today world over, to be animate, living, or rather to be a collection of living beings—each with their own intelligence, perception, and feeling.

Long before they were winged miniature confections, faeries were themselves forces of nature and a living presence in the land. In one of the most popular origin stories about faeries, it is said that they are the angels who could not decide what side to take when the devil challenged God and was subsequently cast out of heaven. There were angels who were on the devil’s side and angels that could not make up their mind which side to take. These angels were also cast out, also fallen, but fallen onto and into the earth, where they became faeries, genius loci—local spirits inhabiting everything from old oak trees to holy healing wells to windswept mountainsides. And while angels are divided into lesser and “arch” angels, in the faerie realm what we have are kings and most especially queens.

There are different faerie queens in different tales, but in Tam Lin the faerie queen is closely tied to the land. She may be the living, liminal expression of the land itself. How do we know? Tam Lin is a member of her court, and he appears only when Janet shows up and is defiling the land or (in the latter part of the ballad) seeking to remove the evidence of her own fertility—a quality in men and women that is traditionally closely tied to the health of the land. This tells us that the faerie queen’s court is activated, its attention drawn, when the land and the people on it are in some kind of duress.

Though Tam Lin is the emissary from the faerie realm that actually encounters Janet, I have always been struck by the fact that he was able to leave the faerie court in the first place. Ostensibly he would need the queen’s permission to do that, just as the queen or king would need to be the ones to tell him what needed to happen for his curse to be broken and freedom won. Could it be that the faerie queen in Tam Lin is less concerned with malevolence and more concerned with teaching something essential?

Which brings us to her curse. In old stories, curses are taken literally. If you are cursed to never have a child live long enough to have it baptized, then you make a baby doll, bring it to church, and baptize it—that breaks the curse. In Tam Lin, the curse that the queen would have placed on the knight at the end of the story would be to lose his gray eyes and have them replaced with the “eyes of a tree.” Literally she would have had Tam Lin stop seeing things through the eyes of a man and instead see things through the “eyes” or from the perspective of a tree.

And here then is the cure. If and when we are able to put aside our own human perspective for a moment and look at a place with the eyes and from the point of view of the other, nonhuman creatures that dwell there, then indeed a healing can happen. The wound that has left a legacy of seeing both lands and peoples as something to be conquered and divided, the hurt that allows a young girl to rashly proclaim that a forest belongs to her and that she may do whatever she wants in it—these broken beliefs, attitudes, and choices can be mended. They can be healed.

As we noted earlier, the faerie queen does not lay down the final curse; she teases it. And in so doing she offers an invitation not only for the lovers in the tale but for everyone who hears the story as well. Try looking in a different way. Try listening more deeply. Before you pick the roses, consider who and what dwells within them, relies on them, and will be affected by your actions. Before you stake a claim, consider what will happen next.

Every queen owes allegiance to something or someone—be it her country, her people, or her understanding of the divine. The faerie queen’s fealty is to the living land itself, and when we listen to a story like Tam Lin, she appears in the long shadows of the trees to remind us that ours is as well.