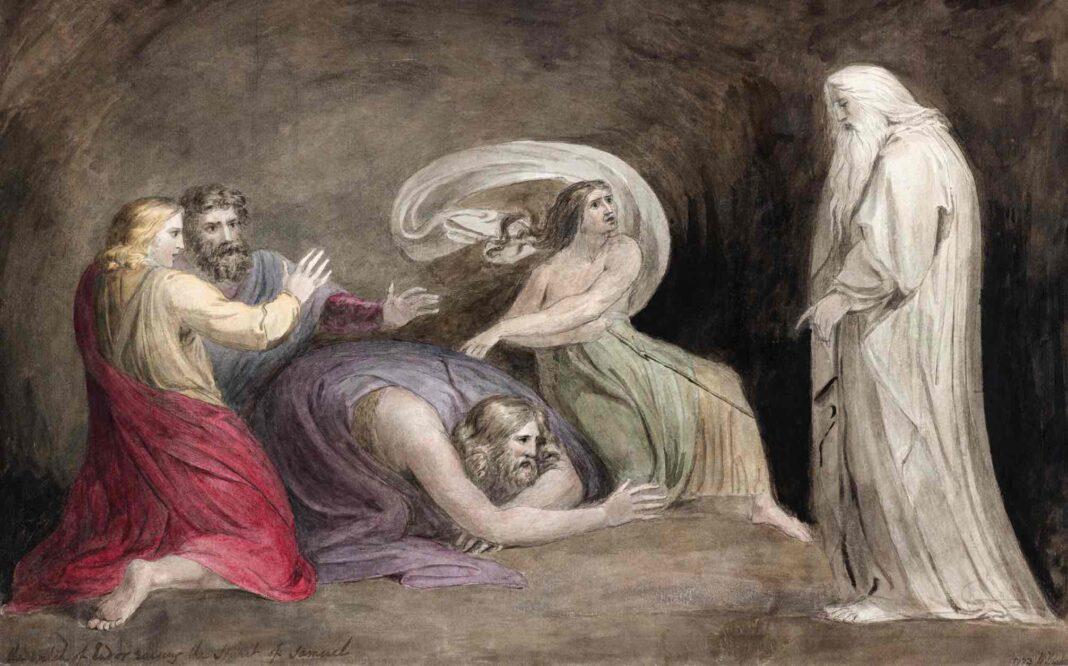

Feature Image:

The Witch of Endor Raising the Spirit of Samuel (1783), by William Blake

Photo ©Ken Welsh. All rights reserved 2022 / Bridgeman Images

Tituba

A dozen years after La Voisin was executed, a handful of tween girls rocked the town of Salem, Massachusetts. For sheer efficiency, no witch hunt can hold a black candle to the Salem Witch trials, which saw 200 people accused (75 percent of them women), thirty convicted, nineteen hanged, one pressed to death, and five dead in jail—all in under a year and a half.

Nine-year-old Betty Parris and Abigail Williams, eleven, started it all by falling into convulsions, hurling things around the room, and screaming in a way that had the rest of the town shouting, “Spectral evidence! Supernatural!” Perhaps because they felt pressured to name names, and perhaps because it was sort of fun to get people in trouble, they first accused three women even less powerful than themselves. One was very poor, one a beggar, and one had a now-famous name: Tituba, a young Caribbean woman enslaved in the Parris household.

Sure, the girls were young. So were the others who joined them in the ranks of the Afflicted, as the witches’ soi-disant victims were known. And you may say that life had been hard on them. Puritanism wasn’t an easy row to hoe, and the area was under social and economic stress after a colonial war with France. Pointing fingers at potential witches was a way for the girls to claim their own power.

But still. Mean girls. They do get a lot of attention by picking on people less lucky than they are.

Most of the accused protested their innocence, but—in a courtroom shocker—Tituba embraced the accusation. Oh yes, she said, she and the devil had an agreement. Plus, there were more witches in Salem, and they were going to take the Puritans down.

So was she a witch? By Puritan standards, almost certainly. She may have grown up with a mélange of African gods and Christian rituals. As to the visions she described of black dogs, red rats, yellow birds, and a book in which she signed her name—only Tituba really knew what she saw or inspired suggestible little girls to see. She named a few names too and identified monsters among the sedate Puritans.

Her surprising revelations turned the hunt upside down, and things really got out of hand. More girls suffered invisible attacks and spontaneous visions, and the Court of Oyez and Terminez was in almost constant session before the governor ordered a halt to the manic proceedings. In May 1693, everyone returned, more or less, to normal life. The Afflicted found they were mostly okay after all, and the accused were released from their jail cells.

Tituba was released too—into the hands of a new owner, since the Reverend Parris refused to pay her jail fees. No one knows where she ended up.

Tituba, I admire your courage. You saw a chance to terrify the witch hunters, and you seized that moment hard. Though your story ends tragically, with further enslavement, for a while you used the master’s tools to tear down his house. In another time, your wits might have made you a queen.

Marie Laveau

Friend to the incarcerated, hairdresser to the wealthy, and worker of powerful charms, Marie Catherine Laveau was in some ways the woman Tituba might have become. She was good-looking, clever, and talented as a midwife and herbalist. She was also intimidating. She knew how to deliver a cutting stare, which would help build her reputation as a practitioner with true powers from beyond. In other words, she was as full of contradictions and possibilities as any other woman with power.

Marie reigned as New Orleans’s most powerful voodoo priestess of the 19th century, when the establishment considered a spiritual path that included the afterlife to be a form of witchcraft. Born in the Vieux Carré in 1801, just before the Louisiana Purchase brought the territory under U.S. control, she never quite fit into the mainstream—but the mainstream flowed to her.

Here’s what’s really remarkable: Unlike most of the women in the club, Marie does not seem to have suffered from being considered a witch in her lifetime. Even though voodoo was officially frowned upon, her good works among the people protected her reputation. To many, she was, and remains, admired (and often feared) folk heroine, though Marie Laveau (1977), her legend is as much a Charles Massicot Gandolfo mishmash of fact and

memory and conjecture as any historical portrait.

The 19th-century American public was fascinated by New Orleans voodoo, which had developed since colonial times into a combination of Catholic and African rituals. The African gods became spirits, sometimes called archetypes, both protective and malevolent. A priestess might invite those spirits to use her body for a while, taking a ride into the living world. The practice was never specifically made illegal, though it did cause unease in the white patriarchy, who feared that the rituals (like any religion arising among enslaved African Americans) would stir up discontent and help organize a rebellion.

Marie’s rise to the priesthood began after an early marriage left her widowed at age nineteen. She set up housekeeping with a nobleman by the fancy name of Christophe Dominick Duminy de Glapion, and she gave birth to between seven and fifteen children, only two of whom survived. She nonetheless found time to dress the hair of New Orleans’s wealthy women, either in her own salon or in her customers’ homes.

Far more than a chatty society stylist, she was savvy enough to work her way into a system of obligation with the servant class. By curing them of various ailments—or if that failed, paying them for information—she accumulated a wealth of secrets that helped her make accurate divinations, or supernaturally informed visions of her clients’ lives and problems. From heartache to family strife to indigestion and rheumatism, she gave sound advice. Did she do it with the help of an enormous pet snake named Grand Zombi? Doubtful—that part of her legend seems to have arisen in 1913, well after her death. With help from the spirits? Most likely; the web of gossip may have helped, but Marie’s divinations transcended earthly knowledge.

She did not share her gifts with the wealthy alone. Her philanthropic side emerged as she tended the sick during outbreaks of cholera and yellow fever, and she helped other women of color learn the skills to better their lives. She also visited condemned prisoners to offer spiritual comfort.

Sure, there is a seamier side to her legend; it all depends on whom you ask. According to one less positive newspaperman, Marie organized “indecent orgies of the ignoble Voudous,” leading many women astray through her spiritualist rites. I rather hope that she did.

Those rites (most likely some exuberant dancing and spirit possessions) may have been the brainchild of Marie’s younger daughter, known as Marie II. She was a public-relations whiz who convinced Marie I to perform mass rituals—most famously, before a group of Even today, if you need a wish granted, you can go to Marie la Première. Find her tomb in the Glapion family crypt and draw an X on the side; turn around three times, knock on the wall, and shout out your wish. If Marie grants it, come back and draw a circle around your X. Don’t forget to leave her a small gift in thanks; Marie may be generous, but she still operates on a system of favors. And she appreciates generosity in others.

Marie, I believe in your kindness, but I also admire your ability to intimidate. Too often, a good heart is crushed in the wheels of propriety; let the power of kindness also inspire awe. If I ever make it to New Orleans, I’m bringing you some juicy secrets.

The Bell Witch

Kate Batts is—and I must say is, not was—equal parts witch and ghost, plus a superstar of American folklore. Best known as the Bell Witch, she sprang from the area around Tennessee’s Red River in 1817 and has inspired countless books and movies. If you’re into tales of the supernatural, you’ve already met her in plot points in everything from The Amityville Horror to An American Haunting. If she were around in the age of social media (and who’s to say she isn’t?), she’d be that girl who’s always on her phone or at the keyboard, making sure her story gets out.

The oral tales of Kate’s doings first became written ones with 1894’s Authenticated History of the Bell Witch, for which newspaper editor Martin V. Ingram interviewed local residents and descendants of the Bell family, the original targets of her supernatural fury. They reported that Kate’s witchy ghost could speak, pinch people, destroy furniture, appear and disappear, and transport herself long distances lightning-fast. She targeted the Bells—particularly Betsey, a young lady of the house—with slaps and pokes, ripping the sheets off their sleeping bodies, and paralyzing the mouth of paterfamilias John, whom she called Old Jack. Kate thought of herself, she said, as “a spirit” who “once was happy but have been disturbed.”

As the spectral witch’s fame grew, people traveled from around the countryside to meet her, discovering that she knew the Bible well and loved to talk about the Bells’ neighbors. In the reasons given for her fury, we find a wellspring of American folklore. Some swore she was angry because Mr. Bell had harmed a Native American burial mound on the land he occupied—perhaps the first time that explanation appears. Some said that the witch wasn’t Kate at all but the spirit of an overseer John had murdered.

And then there’s adolescent rebellion. Whoever this spirit-witch was—I’ll keep calling her Kate, since that’s what she called herself—she apparently did not want Betsey to marry the boy who’d been courting, and she had it out for Old Jack in particular. While she occasionally sang sweetly to Lucy, John’s wife, she cursed him right and left and eventually poisoned him. Naturally, her reputation grew thereafter, and so did her doubters, foremost of whom was an anonymous writer who in 1856 put forth a certain, and by now predictable, theory concerning Kate and Betsey.

We’ll grant that author one or two points: Maybe Betsey, a young girl squirming under her father’s thumb, felt that her one shot at happiness lay in spells and impersonations, and she took power where she could find it. It’s possible that she had a gift for ventriloquism and used it to stage the Bell Witch’s visitations.

The anonymous writer contradicts earlier reports in a significant way: He (oh, it was probably a he) claimed that Betsey was trying to bring her beau to the altar. Ingram disagrees with the theory, noting that when Betsey called off the wedding in 1824, the witch-spirit disappeared. She reappeared to the Bells just a few times afterward.

Well, if the witch was Betsey, I have to applaud her resourcefulness. She not only scared the tar out of a few people (including, perhaps, her suitor), but she also drew attention to acts of racial injustice with the old burial mound and even, in a roundabout way, the story of the overseer—not to mention the patriarchy embodied in her domineering father.

Whoever she was, the Bell Witch demands respect for having thrust a small Southern town into international consciousness. And it seems she isn’t done yet; Tennessee’s odd events and house hauntings are still attributed to Kate today, and the cave where she’s said to linger is a top tourist attraction.

Kate—or Betsey—I relish your endless invention, and I choose to believe you did not kill Old Jack. If happiness does have the power to soothe spirits and stop people from pinching each other, I hope there is more happiness in the world, and fast.

Here’s something that might make Kate happy, and perhaps the spirits of all the others accused, rightly or wrongly. Speak the new words of power aloud: