If I were to say to you, “A woman robed in white, standing next to a bowl, holding a silver ewer,” you would likely know exactly which scene I am referring to. It is a tableau conjured by J.R.R.

Tolkien from the mythic consciousness, iconic as an image from the tarot, yet what rises in your mind—Galadriel hovering over her mirror of water—likely has been in some way shaped and touched by the imagination and artistic hand of Alan Lee.

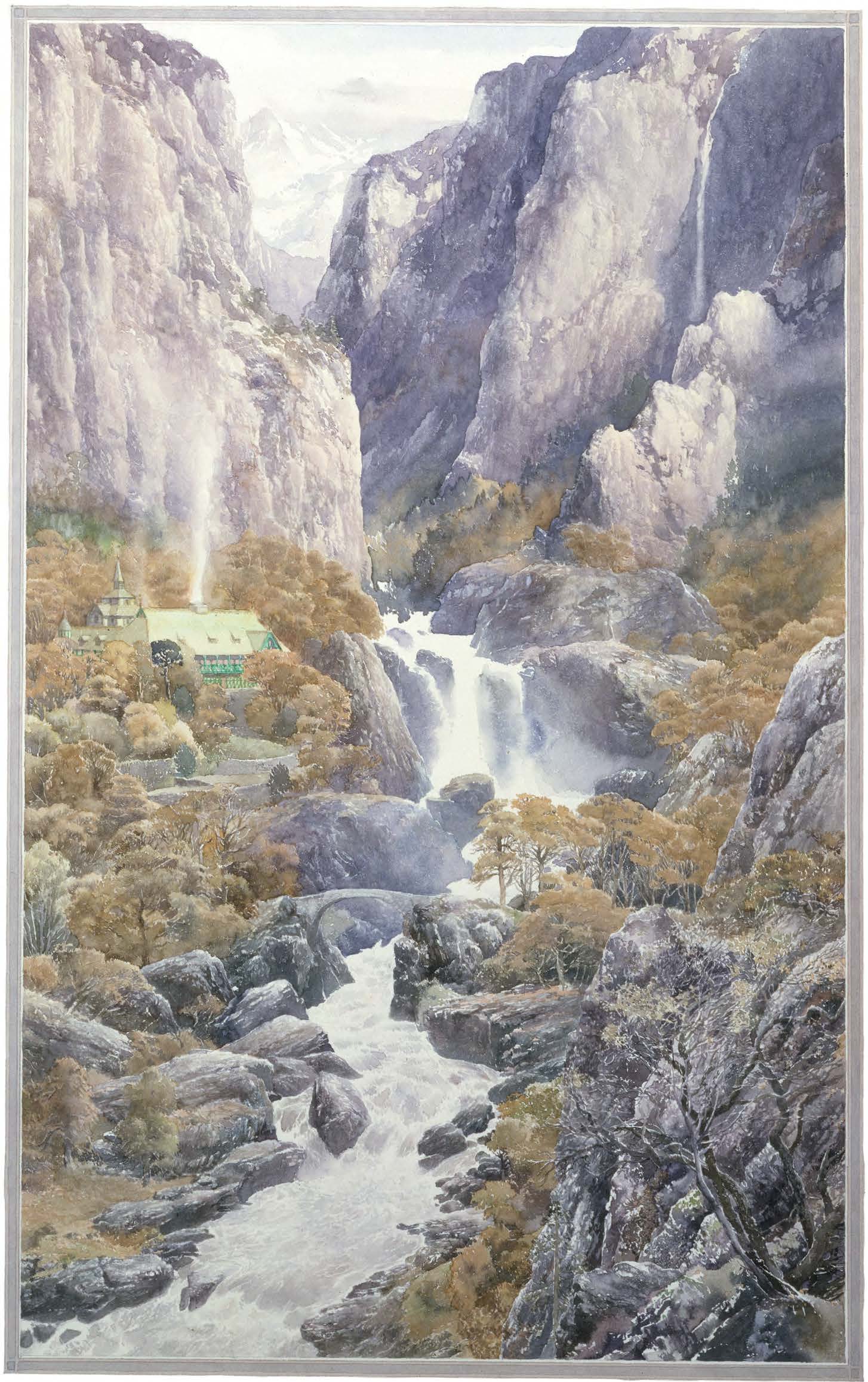

Lee has become one of the best known illustrators of Tolkien’s work, beginning with the 1991 The Lord of the Rings Centenary Edition, and then revisiting his contact with the author’s work with The Hobbit, The Children of Húrin, Tales of the Perilous Realm, and The Tale of Beren and Lúthien, released last June. He is renowned for his achievements as one of the chief conceptual designers for Peter Jackson’s epic The Lord of the Rings and The Hobbit trilogies, and he won an Academy Award for Best Art Direction in 2004 for The Return of the King. Lee’s mythic bona fides are substantial. He has illustrated an edition of the medieval Welsh legend cycle The Mabinogion. His Merlin Dreams is a collaboration with famed fantasy writer Peter Dickinson, and Faeries is his storied and stunning partnership with fellow Devon artist Brian Froud.

Lee’s collaboration with David Day on the 1984 work Castles visually interpreted the writings of Mervyn Peake, Bram Stoker, and Edgar Allen Poe, in addition to giving the world its first glimpse of his interpretations of Tolkien. From nature scenes to war scenes, Lee’s art spans an incredible range, just as Tolkien’s books do. And like the author, the artist also has a recognizable orientation through his hand: A lover of trees and forests, Lee frequently entangles his scenes with nature. Even his war scenes can be part of a cyclic, natural world. For our special Tolkien issue, Faerie Magazine is proud to present our conversation with Alan Lee, who has had such a profound effect on many imaginations. We ask him a question that he has never been asked before as we talk with him about things that were, things that are, and things that shall yet come to pass.

Laura Marjorie Miller: Please describe for us the atmosphere in Devon, where you live, and tell how you draw upon it for your illustrations of Middle-earth.

Alan Lee: Chagford is a small town close to the moor and the beautiful Teign valley. You can walk in any direction and within a short while find yourself in surroundings that look like the setting for a medieval romance, a fairy tale, or an ancient pagan legend. The landscape of Dartmoor has been inspiring stories and artists and writers for very many years. There is something very Shire-like about the way the farms and villages are half hidden in the valleys and sometimes half buried in the side of a hill, under their heavily thatched roofs. Having all this reference to hand is very useful, and I rarely go out without a sketchbook in my pocket.

LMM: What is your favorite kind of leaf to illustrate?

AL: This is the first time I’ve been asked this question. When illustrating “Leaf by Niggle” for Tales From the Perilous Realm, I used beech leaves, but I think the ones I enjoy drawing most are autumnal leaves, desiccated and decomposing.

LMM: Is there a difference in your experience between drawing from your imagination and evoking specific landforms, like in New Zealand, when you were designing for the films?

AL: They are both enjoyable and feed off each other—the real landscapes provide information and inspiration to make the imaginary places more believable and rich in credible detail, and the stories I’m trying to evoke in my work seep into the real landscapes I’m walking in or flying over! It is the real landscapes of Dartmoor, Scotland, or Wales that I find most inspiring though. Partly because they have had a longer influence and place in my life, but also they evoke so strongly the myths and other stories that have had such a big role in forming my imagination.

LMM: How much research is involved with getting details right for architecture and costumes?

AL: Research isn’t the most enjoyable part of what I do, but it is necessary. In pre-Google days I would make many trips to locations, museums, and libraries, and photograph and sketch to collect material that may be useful for a particular project or for something that may be needed later. I really don’t like working from photographs. It is essential at times but no substitute for sitting in front of a person, place, or object and sketching it from life.

LMM: Have you ever done illustrations for Tolkien books that didn’t get used?

AL: There have been a few illustrations that didn’t make it into print and a huge number of sketches, doodles, and working drawings that weren’t done for publication. Some of these are now in The Lord of the Rings Sketchbook, and I hope that more of them will be published in another volume. Because they are not subject to the same pressures as work done for print, they have a light and exploratory quality that I enjoy.

LMM: Do you reread Tolkien? What is your rereading process like? Do you read parts, go deeply in? Is there any Tolkien that you haven’t read?

AL: I haven’t started Tolkien’s translation of Beowulf, or The Fall of Arthur. I’ve reread the books, but mostly in a piecemeal way, as I’ve been working on various representations of the stories and characters, rather than from start to finish. It’s important to keep on going back to the text rather than relying on impressions and memories of it. There’s always something new to discover.

Read the full interview with Alan Lee in the Spring Issue: Print // Digital

I truly appreciate this post. I?¦ve been looking all over for this! Thank goodness I found it on Bing. You’ve made my day! Thx again

[…] Newman’s carvings, Tolkien’s “On Fairy-Stories,” Hobbiton in New Zealand, Alan Lee’s drawings and paintings of Middle-Earth, Daniel Reeve’s cartography for Jackson’s films, a glimpse into “Norwegian wood […]

I really can’t believe how great this site is. Keep up the good work. I’m going to tell all my friends about this place.