One fine day last spring, I met my sister-in-law Rita for lunch. She was clutching a chunky paperback with an embossed cover, the kind, so I thought, that I would never read. Rita told me my brother had bought her the entire eight-volume boxed set of Outlander, by Diana Gabaldon, the blockbuster series about time travel in the Scottish Highlands, because she had become so obsessed with the first book. She was sad to be nearing the end, she said, and may need to go back to the beginning and start all over again. (At an average of 1,200 pages per volume, that tells you something.) But be warned, she said. There’s a lot of sex in those stories.

I’m not sure why she needed to warn me, but I was intrigued—not about the sex, it was the time travel!—and so I bought the first volume, Outlander. It was impossible to put down, and I’ve been devouring those chunky paperbacks with the embossed covers ever since. And now I’m sad to be nearing the end too. (Though there’s good news on that front: Gabaldon is working on a ninth book, Go Tell the Bees That I Am Gone, and claims that she’ll make it an even ten and be done.)

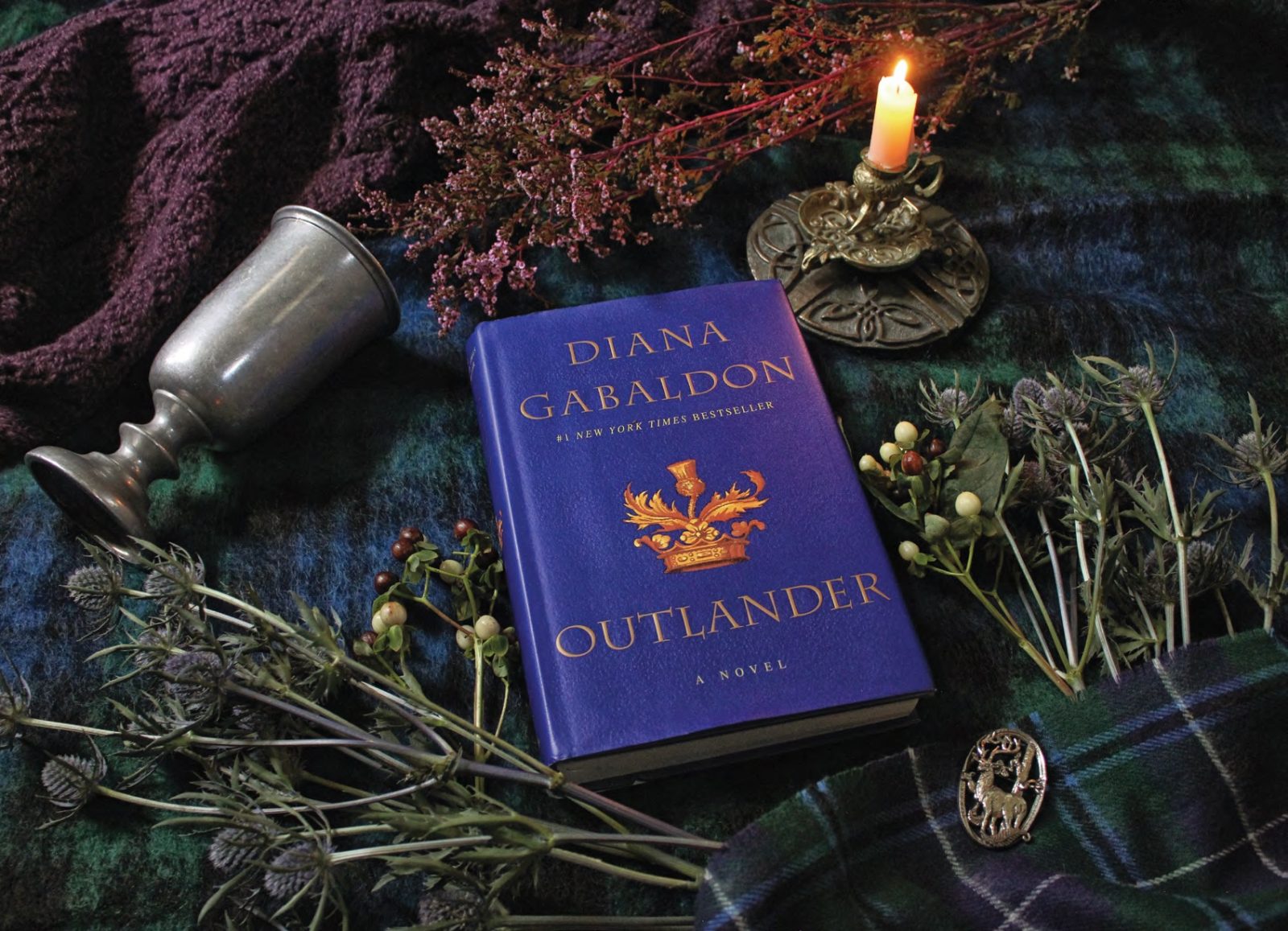

Outlander is a smart, well-written, impeccably researched page turner that is impossible to categorize or define. The New York Times called it “genre-bending.” A rich, bubbling stew of romance and historical fiction, it is also a thriller, thick with magical enchantment, herbal lore, and more. Whatever you call it, one thing is certain: It’s an international publishing sensation. Outlander has sold well over 30 million copies in 44 languages around the world since the first book was published in 1991. It was made into a hit TV series on Starz and was recently renewed for its fifth and sixth seasons. The show costars Sam Heughan, the hunky Scotsman, in the role of Jamie Fraser, and Irish-born beauty Caitriona Balfe as Claire Randall. And maybe someday Outlander will be a Broadway musical—there have been talks—but possibly not while the TV show is running.

The story centers around Claire, a former combat nurse, who takes a second honeymoon to Scotland in 1946 with her husband, Frank. Out for a walk one morning near Inverness, she stumbles upon Craigh na Dun, an ancient circle of stones that turns out to be a portal to the past, and Claire slips through to 1743. Before she can even blink an eye, she finds herself in mortal danger and is rescued by the dashing Highlander Jamie Fraser.

If you have read the books, you know what happens next, and if not, well, you are in for a great treat. But be warned: Don’t pick up these books unless you are prepared to not put them down. And if you can, read the Outlander books in sequence before you watch the TV series. That way, you’ll have the characters take shape in your imagination before the actors get inside your head. Gabaldon agrees. “The show is a very good companion to the books,” she says. “But it’s not a replacement.”

I start with a kernel—an object, a vivid image, a line of dialogue—and I’ll write down a line or two that attempts to capture where that was.

Creating a richly layered, exquisitely detailed, multisensory world is important to the author, and she is really, really good at it. In fact, the attention to detail is a main reason Outlander resonates so powerfully with readers—it makes the books transportive. Gabaldon, who is really fun to talk to, is extremely articulate and strongly opinionated (a bit like Jamie Fraser!) and has mastered a writing style that propels—no, hurtles—readers forward. It immerses them squarely in a sensual world of her creation, and it turns out that is exactly what Gabaldon is going after. “I start with a kernel—an object, a vivid image, a line of dialogue—and I’ll write down a line or two that attempts to capture where that was. Writing immersively is a matter of technique but also seeing what’s there that’s having a sensory effect,” she says. “If you use any three or more of the five senses in a scene, that scene will become three-dimensional, and readers will feel like they’re in there. Most new writers use sight and sound, but not touch and smell.”

Gabaldon is not a linear writer, and that comes through in her books, which twist, turn, and loop back around in ever surprising and delightfully elliptical ways. In fact, she feels very strongly that most people, from grammar school on up, are “brainwashed into thinking we must write from beginning to end, create a rough draft, and polish it. Most people’s minds don’t work that way,” she continues. “I don’t work on rough drafts at all. I fiddle with a sentence until it gets as good as it can be. I am the absolute opposite of a linear writer.”

Some writers chart and map things out to the smallest detail. But Gabaldon does not. She keeps writing “in a back and forth manner”—doing her research at the same time—and sees where her characters lead her and how their rapport moves the story forward. Gabaldon is a fast talker, and her writing is, in part, a process of talking to herself: “How do I describe this 18th century crystal goblet? Oh, it’s winter light. It’s mid-afternoon. I have to say it’s ‘cold blue light’ because it’s a winter afternoon.”

If you are awed by the complexity of the Outlander plots and have ever wondered how Gabaldon weaves those many gold threads together into that shimmering tapestry, it is astounding to think about how serendipitously it all got started. Gabaldon is incredibly prolific—and pragmatic—and has always had at least three projects to work on at a time.

In the early days, she says, “I had to keep going to get paid.” If she came to a place in the novel where she got stuck, “I would stop,” she says, “and pick up a software review to write. If I got stuck again, I’d go to work on a grant proposal. Some people get stuck and stop for coffee or walk the dog. But those people don’t always come back, and they don’t produce. I’d reach the end of the evening with a lot of work done.”

Now, of course, those software reviews and grant proposals are ancient history. Instead there’s the challenge of keeping the novels’ momentum going for readers who started with the first book and have read the books in sequence while also providing enough context for those who’ve stepped into the middle of the series. “In a series, you want someone who picks up your book at an airport to enjoy it but not bore followers who were there with you from the beginning.” She calls it “jacquard writing”: “I just pick up a few threads here and there. Given the size of the books and the complexity, it takes increasing ingenuity to engineer it.” And like every writer, she occasionally gets stalled and loses momentum herself. But when that happens—she calls it “a cold day”—Gabaldon turns to one of the 2,200-plus books in her office library for help. “I pick up one of the books, flip through it, it triggers something, and it picks up the writing.”

Though she always wanted to write, Gabaldon didn’t set out to be a novelist. In fact, she is a scientist, with a bachelor of science degree in zoology from Northern Arizona University,

a master’s degree in marine biology from the University of California, San Diego, Scripps Institute of Oceanography, and a Ph.D. in quantitative behavioral ecology from Northern Arizona University.

In the 1980s, she was an assistant professor of environmental studies at Arizona State University, in Tempe, and also juggled her two other jobs as a software reviewer and a grant writer. She “had slid sideways into having an odd expertise in scientific computation—using computers to do science.” As if that wasn’t enough, she has a husband and, at that time, her three kids were under the age of six.

And then it hit her: “At 35, I said to myself, Mozart was dead at 36. I don’t want to be 60 and not have written a novel.” Gabaldon decided to try and write a book “for practice” to see if she could do it. “The determination to write came first,” she says, “then I asked myself, What am I going to write At Doune Castle about? What would be the easiest thing for me? I’m a research professor, and I know I can do research. I could research historical fiction!” With that decided, she needed to figure out “the what and where”—what period in history, what part of the world. “I was just casting around: American Civil War? Italy in the time of the Borgias? Scotland was a pure accident.”

One thing she did know was that the novel would need conflict. She happened to see an episode of Doctor Who, with a young Scotsman wearing “a rather fetching kilt.” The next day Gabaldon went to the library—this was 1988, before Google—and typed “Scotland,” “Highlands,” “18th century” into the computerized card catalog. She took a bunch of books home, and she was hooked. “Scotland has a very rich cultural tradition,” she says. “Scots hold grudges. They’re very opinionated. And there are stories under every rock in Scotland.” Our hero, Jamie Fraser, was named after the fetching Scotsman Jamie from Doctor Who.

Not surprisingly, Claire’s character was more of a challenge. On the third day of writing the novel, Gabaldon went back to the library and ran a quick search of Scottish history, looking for conflict. She found the Jacobite Rising. “I thought it would be good to have a woman play off the men in kilts,” she laughs. “If it was the English versus the Highlanders, there would be plenty of conflict if I introduced an Englishwoman.”

But Claire was even more of a handful than Gabaldon bargained for. “I fought with her for two or three pages, but she just kept making smartass modern remarks, so I said to her, Okay, I’ll figure out how you got here later.” And that, of course, evolved into time travel.

As she writes, Gabaldon breaks her characters into three types. There are the “onions,” like Jamie and Claire: “I add more layers the more I work with them.” And there are the “mushrooms” like Lord John Grey or Mr. Willoughby: “They just pop up. I don’t expect them or plan for them.” The “hard nuts” are “the people you’re stuck with because they are real historical people or they appear in the plot, like Brianna.”

Gabaldon has lived in the same house in Phoenix for thirty years. She has two dachshunds and has been happily married to the same man, Doug Watkins, for forty-seven years. She is extremely approachable and seems to love to engage with her readers, who can find her on TheLITforum.com, an online literary hangout where Gabaldon found “a free-floating twenty-four-hour literary cocktail party” many years ago when the site was in an earlier incarnation. It now has an entire section called the Diana Gabaldon forum, where fans of all things Outlander can engage with each other—and her. When she’s not writing, she’s reading. Gabaldon learned to read at age three and never stopped.

When asked what she likes to read at the moment (aside from tomes on Scottish history), she says she has “a particular taste for Celtic crime novels by Ian Rankin, Adrian McKinty, and Christopher Brookmyre.”

Now Gabaldon has come to a place where she’s not only polished her craft but, still the professor at heart, has a lot to share with budding writers. Occasionally, she’ll retreat to her old family home in Flagstaff to write in seclusion, which she loves. But it’s not necessary. “The act of writing will oil your synapses. Even if you have ten minutes a day to write a novel, eventually, you’ll get there,” she says. As E.L. Doctorow once said, “Writing is like driving a car at night. You never see further than your headlights, but you can make the whole trip that way.”

“Early on, I decided if it turns out that I have no imagination, I can steal things from history,” Gabaldon laughs. “It worked out pretty well.”

I’d read the books after watching the show otherwise you’ll get frustrated by what was left out.

The books are the books and the show is the show. I love the whole Outlander universe!

Twice Claire has used an ancient stone circle to travel back to the h century. The first time she found love with a Scottish warrior but had to return to the 19 to save their unborn child. The second time, 20 years later, she reunited with her lost love but had to leave behind the daughter that he would never see. Now Brianna, from her 19 vantage point, has found a disturbing obituary and will risk everything in an attempt to change history.