Feature Image:

Ulysses and the Sirens (1891), by John William Waterhouse

–––––––

When people ask me which of the many beautiful Pre-Raphaelite paintings is my favorite, I always mention the beauty of Dante Gabriel Rossetti’s pouting maidens or John William Waterhouse’s swirling fabric, but I’m holding back. Just between you and me, my favorite Pre-Raphaelite painting must be Edward Burne-Jones’s The Depths of the Sea (1886). Good heavens! An absolutely gorgeous young sailor is being dragged to his watery grave by a mermaid and doesn’t she look pleased with herself ? The absolutely glorious oddness of the whole piece attracts me in rather unsettling ways, and I find the mermaid’s direct, conspiratorial gaze draws me in like an unsettling motivational poster, as if she is whispering, “Come on, you can drag a sailor to his doom too!” I was never the painting’s intended audience, and Burne-Jones’s intention was never to inspire women in their late forties to start recreationally drowning men. He meant it as a warning and a visceral expression of a personal, if not societal, terror—that given half a chance, all women are dangerous.

These days, you would be forgiven for thinking that mermaids are fairly benign creatures. From Disney’s The Little Mermaid to the Starbucks twin-tailed siren, these aqua-maidens appear to be playful, romantic beings with a shell bra and a caffeinated beverage as their only aims in life. This was not always the case, and in fact for centuries, mer-ladies were seen as actively destructive and scandalous. Whether they are in the form of sirens, nixies, or Jenny Greenteeth, the river hag (which I grant you is a bit rude), watery women have been feared and desired in equal amounts. It is therefore unsurprising that these moist temptresses were such tempting subjects for artists, keen on showing their skill on rending both the movement of water and a nice pair of bosoms.

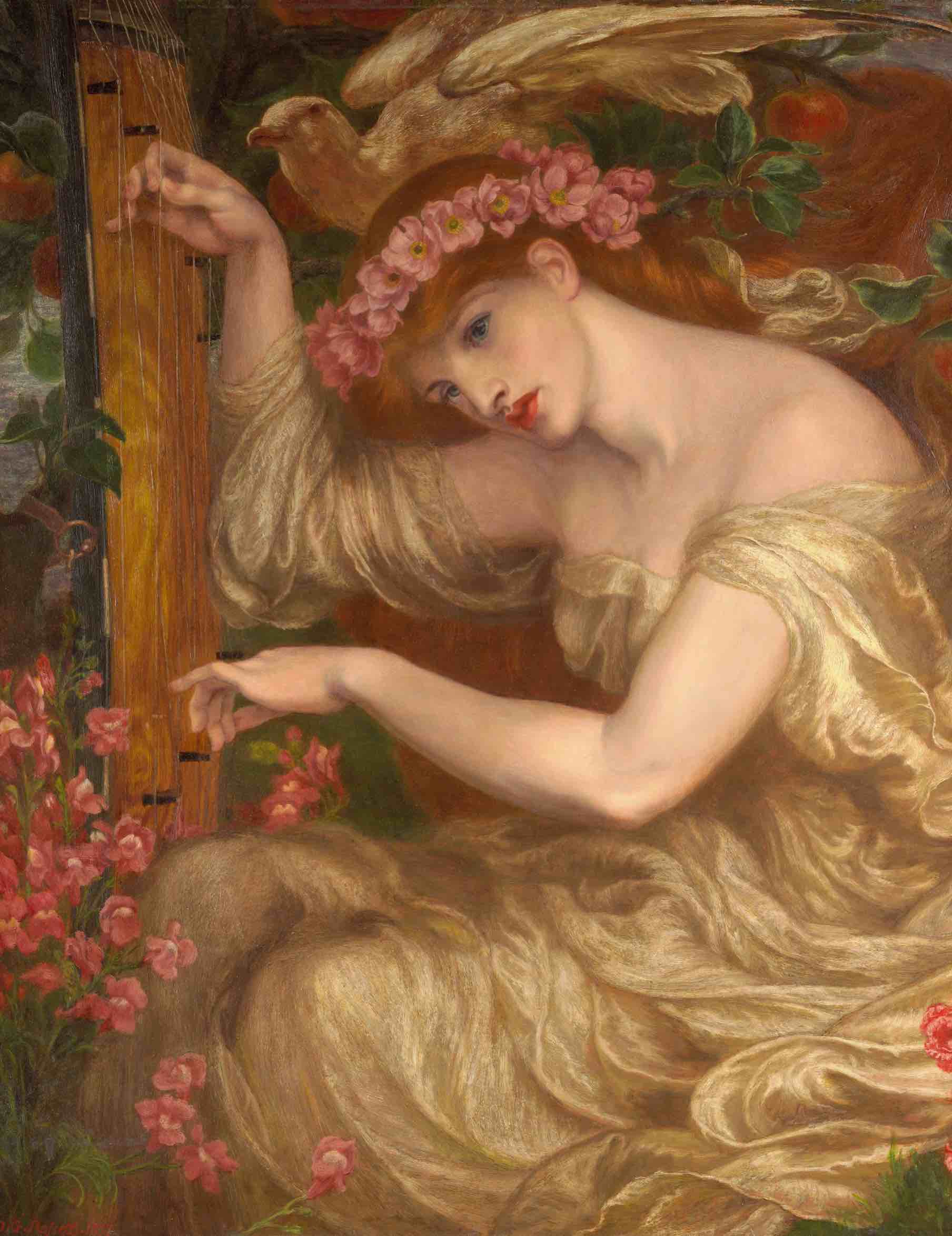

For as long as we have had ships, humankind has had shipwrecks. Luckily, there were women who could have the blame assigned to them in the form of tricksy mermaids or sirens. These enchanting half-women, half-fish could lure unlucky sailors to their doom with their beautiful singing voices. Some mythologies saw these creatures as half-bird, flying over the boats, singing so sweetly they could absolutely unstoppable as they sank the boats and drowned the sailors. These sirens appeared in The Odyssey, with Ulysses (a.k.a. Odysseus) deliberately sailing into a mermaid-infested area out of curiosity after taking the precaution of stuffing his crew’s ears with beeswax and tying himself to the mast. In John William Waterhouse’s dramatic 1891 depiction, the crew of the ship are bombarded with monstrous birds with beautiful faces. One has even landed next to a poor lad on the side of the boat. As Ulysses called to be released, his crew merely tightened the bonds until they got past these terrible sirens, who having been rejected, perished.

According to Leonardo da Vinci, the mermaid’s song would lull the unsuspecting sailors to sleep, then she would climb aboard and kill the slumbering men. This brings me to a very thorny point: So do mermaids have legs or tails? When I read about da Vinci’s stealthy mermaids sneaking aboard, I got as far as them getting onto the deck and then imagined them floundering around in a very ungainly manner, making an awful lot of noise. Artist Arnold Böcklin imagined the merfolk as having decidedly fishy legs, shimmering with silvery scales from the thighs downward but discernibly separate, all the better for climbing onto ships and committing murder.

A way around this problem seems to be that most mermaids, or at least those up to no good, have legs. Quite what makes them a mermaid in this case, rather than a woman who enjoys murdering in water, I’m not sure. In Gustav Wertheimer’s The Kiss of the Siren (1882), a naked lady is dragging a young sailor over the side of his boat while kissing him. In such rough weather, he really should be paying a bit more attention to remaining afloat, but then the mermaid is awfully pretty and extremely nude, so maybe keeping his boat upright is not high in his priorities. In contrast, Knut Ekwall’s fisherman looks rather more perturbed at being seized by the glorious mermaid as she seems to have erupted from the sea, bosom aloft. She is clearly interfering with his rudder, and those sorts of shenanigans have very serious marine health and safety implications.

For our ancestors, the perils of mermaids were not simply a problem of ancient times. In the 18th century, newspaper articles abounded with reports of fishermen catching both mermen and maids, but rather than being tempted or overpowered by these “surprizing fish” (as a local paper in 1738 called them), the fishermen immediately killed them and took them back for display. As late as 1870, one newspaper reported that Scotland was the last stronghold of mermaids and that they were current all around the coast. A Victorian poetic defense by Samuel Lover, entitled “The Irish Mermaid,” told how the mermaid was entirely innocent of such crimes, and the sea loved the mermaid so much, it wrecked the boats in order to bring her treasures. In fact, there are many images of defenseless and attractive mermaids being scooped into the nets of lucky fishermen, including The Sea Maiden (1894) by Herbert Draper. Rather than coming aboard to murder them all, the poor maid is being hauled in with the catch, much to the lusty disbelief of the crew. I think that should be a sobering warning against skinny-dipping, to be honest.

It must be addressed that despite the modest clamshell bra that I’m sure we all thought was standard issue for mermaids, most of them seem to merrily cavort around in the nude. I suppose that makes tempting fishermen to their doom a little easier, as the only thing a fisherman likes more than fish are boobs, apparently. The link between mermaids and sex has centuries of history; Mary, Queen of Scots, used the heraldry of a mermaid, which became derogatory slang for a promiscuous woman after the death of her first husband. The link between mermaids singing and female musicians, or courtesans, also touched on the idea of a musically talented, unmarried woman who brought danger in the form of sin and autonomy. While it is commonly seen that these women, steeped in sin and scandal, fit perfectly into the mermaid role, it could be argued that what Mary, Queen of Scots, and the unmarried women share is independence and power, however slight. A woman with freedom is a danger, as she is a threat to the status quo. Better, then, to see them hampered by a fish tail, easily caught in fishermen’s nets.

As a side note, in my research I was disappointed to find out that mermen are not so common, and my chances of being dragged off into the ocean by a handsome, singing fish-man are decidedly low these days. In past and, some would argue, happier times, women were given the warning that they were in danger of being carried off if they ventured to the shoreline without the protection of their husband. These strappingly handsome fish-men wore lobster claws in their hair and were ill-tempered and lustful, but for some reason they rarely appeared in 19th century art, apart from images of a frolicking family group as in Böcklin’s example. I moved to the South Coast of England twenty years ago, so mermen have had ample opportunity to carry me off (it might take a couple of them, I admit), but thus far I have been unbothered as I walk unchaperoned by the sea. I’m trying not to take it personally.

Aside from the folk tales of nixies and Jenny Greenteeth, it has to be wondered how mermaids went from being a bonus catch for lucky fishmen to being man-drowning harridans, fixed on committing salty massacres. It is 19th century art where you can see this change expressed most clearly. If art is anything to go by, you could hardly get near the beach in Victorian times for the number of crooning lovelies, hell-bent on wrecking ships and having it away with doomed fishermen. From Rossetti’s The Sea Spell (1877) to Frederic Leighton’s The Fisherman and the Syren (1856–58), water-borne temptresses lined the shore, singing and endlessly combing their hair. No longer “water hags,” mermaids were beguiling and beautiful, and their victims could not see the danger before it was too late. It is tempting to link the escalation in mermaid-related violence to the growth of the female suffrage movement. From the middle of the century onward, women were broaching the male bastion of education, of thought and reason and opinion, plus—to add insult to injury—these tricksy women also wanted the vote. These paintings of mermaids can be seen as whispered warnings, from one man to another: I know they look beautiful, but beware! They hold power that will destroy us! The men in the paintings are by and large utterly helpless in the presence of a beautiful woman and hand over their very lives willingly. Conceding any control to women therefore becomes an act fraught with danger. If you give women the vote, what will they want next? It is a testament to how wise and powerful chaps are that they managed to resist women, who are tempting and murderous and apparently able to harness the wind and sea. No wonder men are in charge …

What should be evident to us all by now is that mermaids are not to be trifled with. Honestly, I think it’s better to extend that to all women, because the mermaids and sirens of Victorian art can’t quite make up their mind if the two are entirely separate. Not only that, as we see in The Depths of the Sea, the comparative physical strength between the great strapping man and the mermaid makes no difference in the outcome. Women will conquer, given half the chance, and they are ruthless and not a little mad, the pictures seem to say. When Charles Dana Gibson drew his archetypal New Woman, watching imperviously as her companion drowns in In the Swim (1900), he connected the aspirational modern woman with men’s timeless fears of sinking in a world where women rise to the surface. Possibly instead of worrying about the temptresses filled with lustful murder, consider that if men are so wonderful, why are women attempting to drown them all the time? The only resolution to all this mayhem on the high seas is to stop being easily tempted by a naked woman with an enchanting singing voice. I don’t mean to victim-blame, but if Odysseus got past them with a bit of bondage and beeswax, then you can too. Also, give women the vote. Honestly, they will feel less inclined to drown you if you do, I promise you.

Kirsty Stonell Walker is a writer and researcher whose passion is bringing forward the stories of women who might have otherwise vanished in history. She’s the author of Pre-Raphaelite Girl Gang and Light and Love and Stunner, a biography of Pre-Raphaelite superstar Fanny Cornforth. Visit her on Instagram @kstonellwalker.