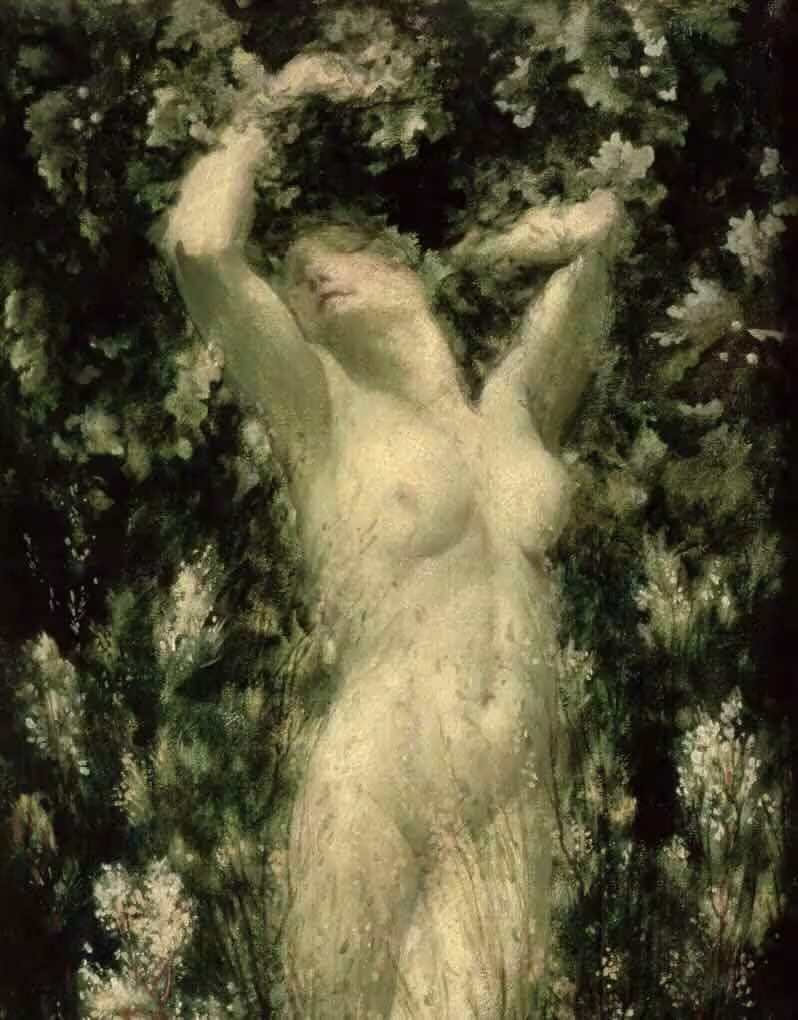

Feature Image:

Night Flight by Kelly Louise Judd @swanbones

She opens her eyes. What does she see in the first moments of her existence? The Mabinogion does not tell us, but we can imagine. She is standing in a forest glade, surrounded by the detritus of her construction: oak branches stripped of their blossoms, the prickly stems of broom, the smooth stems of meadowsweet. She was made from their flowers, which sounds very romantic. But to be honest, it reminds me of either Ikea furniture or Frankenstein’s monster. In that forest glade stand the men who made her: Math son of Mathonwy, king of Gwynedd, and his nephew Gwydion son of Don. Both are powerful magicians. Here is the official description from the Mabinogion, as translated by Lady Charlotte Guest: “So they took the blossoms of the oak, and the blossoms of the broom, and the blossoms of the meadow-sweet, and produced from them a maiden, the fairest and most graceful that man ever saw. And they baptized her, and gave her the name of Blodeuwedd.” But what does Blodeuwedd see with her newly opened eyes? She has no idea who she is, what men are, or why she has been made. She must be so confused.

As you might be at this point, if you are not familiar with Welsh mythology. So let’s go back a bit, because the story of Blodeuwedd (pronounced Blo-dey-weth) is a small part of a larger story that begins before her creation. That story starts with another woman, Arianrod, Gwydion’s sister. As so often happens in Welsh mythology, Math lives under a strange condition: Except when he is at war, his feet must rest in the lap of a maiden. In the fourth part of the Mabinogion, which is named “Math son of Mathonwy,” Gwydion’s brother Gilvaethwy falls in love with Math’s lap-maiden, Goewin. Through an elaborate ruse, Gwydion tricks Math into going to war, and while Math is away, Gilvaethwy forces himself on Goewin. When Math returns, Goewin tells Math that she is no longer a maiden and angrily recounts what Gilvaethwy and Gwydion have done. Math takes her as his wife, and to punish the brothers, he turns them first into a pair of deer, then into a pair of wild boar, and finally into a pair of wolves. Meanwhile, he must find another lap-maiden. Gwydion suggests his sister Arianrod. Why does Math listen to anything Gwydion says at this point? Your guess is as good as mine, but trickster figures like Loki, Hermes, and Gwydion always seem to get their way.

Math summons Arianrod and, to test if she is indeed a maiden, tells her to step over his magical wand. She steps over the wand and immediately bears a son, as well as what the Mabinogion describes as “some small form.” Angry that she has been exposed as not-a-maiden, Arianrod storms out of the room. Gwydion scoops up the small form and hides it in a chest. One day he hears a cry from the chest—it is a second child, which begins growing very quickly. When this second son is old enough, Gwydion takes him to Arianrod and introduces him as her offspring. She is so furious at this reminder of her shame that she lays a curse on the boy: He shall never have a name unless she names him. Of course Gwydion tricks her into giving the boy a name, Llew Llaw Gyffes. When she curses him again, saying that he will never have arms and armor unless they come from her, Gwydion tricks her into giving them to Llew. Arianrod curses Llew a third time: He shall never marry a human woman. This is where the story of Blodeuwedd begins.

The most beautiful description of the creation of Blodeuwedd was written by the Irish poet Francis Ledwidge, in a poem titled “The Wife of Llew”:

And Gwydion said to Math, when it was Spring:

“Come now and let us make a wife for Llew.”

And so they broke broad boughs yet moist with dew,

And in a shadow made a magic ring:

They took the violet and the meadow-sweet

To form her pretty face, and for her feet

They built a mound of daisies on a wing,

And for her voice they made a linnet sing

In the wide poppy blowing for her mouth.

And over all they chanted twenty hours.

And Llew came singing from the azure south

And bore away his wife of birds and flowers.

This is even more romantic than the description in the Mabinogion, but Ledwidge’s reference to “birds and flowers” hints at the darkness of Blodeuwedd’s story, which will end with a very different kind of bird than that famous songster, the linnet.

Imagine that from the moment you open your eyes as a sentient being, you are told you have been made for a particular purpose: to be the wife of a man you’ve never met and certainly did not choose for yourself. How could Math and Gwydion have thought this would end well? Blodeuwedd marries Llew, but one day while he’s away from his castle, she sees Gronw Pebyr, the lord of Penllyn, out hunting. She invites him and his men to spend the night in the castle, and as they sit together by the fire, she falls in love with him, and he with her. But how can they be together? There is only one way, Gronw tells Blodeuwedd: She must find out how Llew can be killed, and Gronw will kill him. Evidently, killing Llew is a complicated matter. When Blodeuwedd asks him how to do it, ostensibly so she can guard against any such thing happening, he tells her that he cannot be killed either riding or on foot, either inside or outside a house. Additionally, he can only be killed by a spear made over the course of a year on Sundays during the Mass. Sure enough, Gronw, who must have a lot of patience, starts making the spear.

A year later, Blodeuwedd tricks Llew into demonstrating the conditions under which the spear could do its dastardly work. He goes to a bathing hut in which there is a tub, stands with one foot on the edge of the tub and the other on the back of a goat—and Gronw throws his spear. With a scream, Llew rises up in the form of an eagle and flies away. Gronw takes over Llew’s land and castle, and the lovers live happily together—or so I presume. In the Mabinogion, we are never told what Blodeuwedd thinks or feels. What did she think of her husband Llew? Why did she fall in love with Gronw? Is she happy to be with him, after Llew has flown off in eagle shape? Does a woman made of flowers think and feel the way a human woman would? I wish we could get inside Blodeuwedd’s head. What would the world of medieval Wales look like to her?

Whatever happiness she has with Gronw lasts only a year. Gwydion finds eagle-Llew perched in an oak tree, summons him down with three short poems, and turns him back into a man. Together, they ask Math to help Llew regain his territory and revenge himself on the lovers. When Blodeuwedd hears they are coming, she flees, but she is overtaken by Gwydion. Once again she stands in a forest glade, facing the trickster-magician. He says, “I will not slay thee, but I will do unto thee worse than that. For I will turn thee into a bird; and because of the shame thou hast done unto Llew Llaw Gyffes, thou shalt never show thy face in the light of day henceforth; and that through fear of all the other birds. For it shall be their nature to attack thee, and to chase thee from wheresoever they may find thee. And thou shalt not lose thy name, but shalt be always called Blodeuwedd.” He turns her not into the linnet Ledwidge identified her with, but into an owl. The Mabinogion goes on to tell us that “Blodeuwedd is an owl in the language of this present time, and for this reason is the owl hateful unto all birds. And even now the owl is called Blodeuwedd.”

Here we have lost something in translation. In the original Welsh, the woman made of flowers was Blodeuedd (without the w), meaning literally “flowers,” and in transforming her, Gwydion renames her Blodeuwedd, “flower-face”—a term that also refers to an owl. Lady Guest omitted this change in spelling. Perhaps she didn’t understand the pun? I have referred to her version because it’s the most poetic, as well as the one most readers are familiar with, but it’s not always accurate to the original Welsh. Like a good Victorian, she elided certain episodes that would have discomfited middle-class drawing rooms. In the original, Math’s punishment of Gwydion and Gilvaethwy includes turning them into opposite-gender animals (for example, a doe and a stag), who must bear a series of young together. Lady Guest’s version does not mention this odd instance of brothers coupling as animals. Gwydion and Gilvaethwy simply return to court with a fawn, a boarlet, and a wolf cub, which are turned into young men by Math’s magic. In Blodeuwedd’s story, Lady Guest’s spelling mistake may simply have been an oversight, but it erased an important part of the narrative. In the Mabinogion, a name is a character’s identity—Gwydion turns Llew back into a man by naming him three times. However, by changing Blodeuedd’s name into Blodeuwedd, he fixes her forever in owl form.

So the flower-woman becomes a bird-woman, condemned to fly at night. Gwydion does not seem to think much of owls, but I find them quite beautiful, and appropriately they are flower-faced. The way their feathers spread outward on their faces, from their sharp beaks and watchful eyes, makes them look a bit like winged orchids. What sort of owl is Blodeuwedd turned into? The most common owls in the United Kingdom are barn owls, tawny owls, little owls, and short- and long-eared owls. All of them have faces shaped like hearts, appropriate for a woman who is punished for loving the wrong man. But if Gwydion intends to punish Blodeuwedd, he does not do a very good job. Instead of taking her back to Llew, which would have been a punishment indeed, he turns her into a mysterious creature of the night, whose cry—Hoo! Hoo!—is the voice of darkness itself. He gives her wings and freedom.

The fourth part of the Mabinogion is about the men: Math, Gwydion, Llew. It focuses on their wars and rivalries, to the point that it could be renamed “Men Behaving Badly.” Even Blodeuwedd’s story ends not when she is turned into an owl, but when Gwydion fights and slays Gronw. The two men agree that, turnabout being fair play, Gwydion may throw a spear at Gronw. But because Gronw claims that “the wiles of a woman” induced him to conspire in Llew’s death, basically saying it was all Blodeuwedd’s fault, he is given the right to protect himself from the spear-throw with a slab of rock. It doesn’t work—Gwydion’s spear goes right through, piercing both the rock and Gronw’s chest. I have no sympathy for him. This section of the Mabinogion could also be called “Men Blaming Women for Their Actions.” The most interesting characters in “Math son of Mathonwy” are the three women: Goewin, Arianrod, Blodeuwedd. I wish I could retell the story from their perspectives—what did they think and feel, while the men were absorbed in fighting one another?

Blodeuwedd, in particular, is such a fascinating character that she has flown out of that tale and into others. Most famously, Alan Garner’s novel The Owl Service, published in 1967 and broadcast as a television series in 1969–70, turns the story of Blodeuwedd into a cyclical myth that must be re-enacted in every generation. Three teenagers spending the summer in Wales are haunted by the story of Blodeuwedd. The girl, Alison, finds a porcelain dinner service on which the floral design can also be seen as owls. She begins behaving strangely, drawing that design on paper and folding her drawings into the shapes of owls, which disappear as though they have flown off by themselves. The two boys, her stepbrother Roger and Gwyn, the housekeeper’s son, also experience strange phenomena. It seems as though the three are re-enacting the triangular relationship of Blodeuwedd, Llew, and Gronw, with its passion and hatred. In the end, Alison must be saved from a mysterious force that seems to have taken possession of her, leaving claw marks on her body as though she has been scratched by owls, while a storm rages outside—even the elements have taken on a mythic dimension. The possession ends only when Roger reminds Alison—over and over, until it seems as though Blodeuwedd hears him—that she is supposed to be flowers, not owls.

In The Owl Service, the story of Blodeuwedd shows its dark, menacing side. But for modern pagans, she is a Celtic goddess of spring and rebirth. Her identity as both flower and bird reminds me of two other goddesses. The first is Flora, Roman goddess of flowering plants, whose festival, the Floralia, was celebrated around when we celebrate May Day. Women have historically been associated with flowers—in Botticelli’s The Birth of Venus, the winds blow flowers toward the goddess of love, emerging on her half-shell, and nymphs wait to wrap her in a flowered garment. But women have also been associated, in a more complicated way, with birds. The second goddess Blodeuwedd reminds me of is Ishtar, as she is depicted on a stone plaque in the British Museum. The plaque, which comes from ancient Iraq, depicts a woman with wings and clawed feet. She stands on the backs of two lions flanked by two owls, like an owl-lion-goddess-lion-owl sandwich. She is nude and does not look in the least ashamed of it. Her hair is looped up in an elaborate hairstyle that was probably the latest thing in ancient Mesopotamia. Her official name on the British Museum website is “Queen of the Night.” I saw the plaque myself, several years ago. It was smaller but also more powerful than I had expected. It reminded me of other bird-women, such as the Greek sirens and harpies.

If Blodeuwedd is indeed a goddess, or if we want to consider her one, I think she must have two sides. She can be the goddess of flowers and springtime. But she must also be the goddess of darkness and perhaps even death (although followed by rebirth). We don’t need to make the choice presented in The Owl Service, because Blodeuwedd is both: flowers and owls. And in a sense, aren’t we all? We have our bright and dark sides, and we would be diminished if we tried to choose one or the other. I like to think that when Blodeuwedd flies out of the Mabinogion on owl wings, she flies into her own story, which will go however she wants to tell it.

Enchanted Living is a quarterly print magazine that celebrates all things enchanted.

Enchanted Living is a quarterly print magazine that celebrates all things enchanted.