Be it tales of wicked fairies, necromancers in their bone palaces, or demons waiting by the roadside to bargain for souls, the macabre has had a hold on the imaginations of readers and writers for as long as there have been stories. And whether it is an element you see as central to your fiction, or something that you want as part of your toolbox, here are some tips and tricks to evoke it.

I once heard the difference between dark fantasy and horror described as being about how the fantastic element is viewed. In horror, it is an aberration, a corruption of the natural order. In dark fantasy, magic is viewed with a sense of awe. Even if a monster is coming to devour you, the world still feels bigger and more interesting for having that monster in it. And that’s why, while I love horror elements, I consider my work to land on the side of fantasy.

It’s also why I will write a lot about giving the reader a specific feeling. As you flip through the pages of this issue, you will have an emotional response to the photography and the art. Visual mediums give that immediate visceral reaction, while the written word has to work harder to earn it. But when it does, it stays with readers for a long time.

Setting

The traditional gothic novel, a genre that originated at the very end of the 18th century and has stuck around ever since (and which includes both Frankenstein and Dracula), was often concerned with a gorgeous but crumbling and potentially haunted manse, its nature mirroring the terrible secrets of its inhabitants.

These days, gothic fiction has a broader definition, but setting is an excellent place to start evoking mood. The location of a story gives the writer a shorthand for promising readers a particular tone and for either playing directly into expectations (the protagonist has rented an Airbnb and it turns out to be a castle crawling with ivy, hung with bone chandeliers, resting on a cliff) or subverting them (the protagonist rented an Airbnb and it turns out to be in the shape of a potato, resting in a meadow of wildflowers).

Think through your options. Make a list. And consider how your story changes with each different setting—what new demands will be placed on the writing, what resonances will be created, and what expectations will be set.

After you choose a place, your challenge will be to make that place feel real. Obviously the best way is by visiting locations and exploring them so that you can come up with the kind of details that make a place come alive to the reader. But I also think it’s worth considering your own experience too. If you’d like to set a story in a crumbling old house, is there one you’ve been in? Is there a castle you’ve walked through on your travels that stuck in your head? And if not, is there a way to alter your setting to bring it closer to something familiar to you? For example, if you want to set your story in a castle and have never been to a real one, perhaps you can have the castle in your tale transported stone by stone by an eccentric billionaire to a place you know well, so that the details you bring to the story will be convincing.

Texture

For me, all fiction starts with a character and a feeling. That feeling is what I call texture.

Macabre fiction—because so much of it is about evoking an emotional response—can lean toward ornate prose, but however voluptuous or restrained your sentences, you must make the world come alive for the reader. We think of world building as being about rules, but it isn’t just rules; it’s tone.

Texture is in the details. It’s a beautiful vampire who, when you get close, stinks of the rotten blood clotted under their fingernails. It’s the difference between the same woods described different ways—dappled with sunlight, motes of pollen floating through the air; or ominous, with wind whistling a haunting melody through the trees. It’s juxtaposed elements, like the cracked remains of beer bottles beside the coiling tracery of ferns.

The minutia of how you describe the world and the characters in it, including their jobs, their cars, and their food, tells us how realistic a story is. For example, a fairy story in which there are oatcakes promises one thing, while a fairy story in which there are cupcakes promises something very different.

World building goes hand in hand with texture. If you’re setting up magical rules, they must align with the tone of the world. If this is a blood-soaked realm, let’s have some sacrifice. If this is a story of a wild wood that evokes fairies and folklore, let’s have some barbed bargains. That’s why I think it’s useful to consider setting and texture before world building—because once you decide on those elements, it’s much easier to figure out how to match the fantastical elements to the tone you’ve set.

Character

Above all else, readers care about characters. No matter how lush your prose or how exciting your twists and turns, nothing can replace developed characters full of secrets and desires, facing conflict.

I often talk about books as being custom-designed torture devices for their protagonists. If a protagonist has a fear, they will be facing it. If they have a complicated past, they will be reckoning with it. And if they have a secret, it’s coming out. And if you want a macabre world, you need macabre characters. That means giving them secrets and desires that are in line with the level of horror and decadence you want in your work.

In The Cruel Prince, I am writing about a mortal girl, Jude, who is being raised in Faerieland by the murderer of her parents. Jude believes she wants to be a knight, but what she discovers is that she has ambitions far beyond that—and that she’s perhaps more like her bloodthirsty foster father than she’s allowed herself to believe. In the same book, we have Prince Cardan, who is laboring under a curse that he only partly understands. Rejected by his family, he’s furious and petty and malicious. It’s only when he’s tricked into wearing the crown of Elfhame that he must ask himself what he could become if he allowed himself to try. Neither of them are particularly nice, and maybe neither of them are particularly good either. But hopefully they’re interesting, and readers can identify with their awful urges, even if they would never indulge them. And because of their pasts, we can anticipate lots of betrayals and bloodshed in their future.

So when you’re thinking about your characters, come up with some possible secrets—maybe even some they’ve kept from themselves. Decide on what they want and what they need. And think about the wounds created by what you know of their past—what was bad enough to have created in them a false idea of the world or themselves.

This isn’t just true of protagonists but also of antagonists. They need desires and secrets, wounds and needs. Dark fantasy is full of fascinating, fully developed villainous figures, from antiheroes to monsters. As readers of macabre fiction are willing to root for the wicked, it is not enough that an antagonist be bad—we need to understand them as well as we understand the protagonists.

Conflict

It is a truism that character is revealed by conflict. And that plot grows out of character. When you get stuck on character, work on the antagonist and the plot. Then go back and see if you view the character in a new way in light of those new decisions and directions.

Inspiration

Drawing from old stories and folklore is a great way to get inspired, and it adds resonance to your fiction as well. Folklore feels true, no matter what we believe about its provenance. Even when the tale you’re referencing is unknown to the reader, it still sparks something in our collective unconscious, something that made it worth telling and retelling.

One way to start is to go back through the stories you’ve loved, the fairy tales and ghost stories and all the rest, and look for where your narrative sweet spots are.

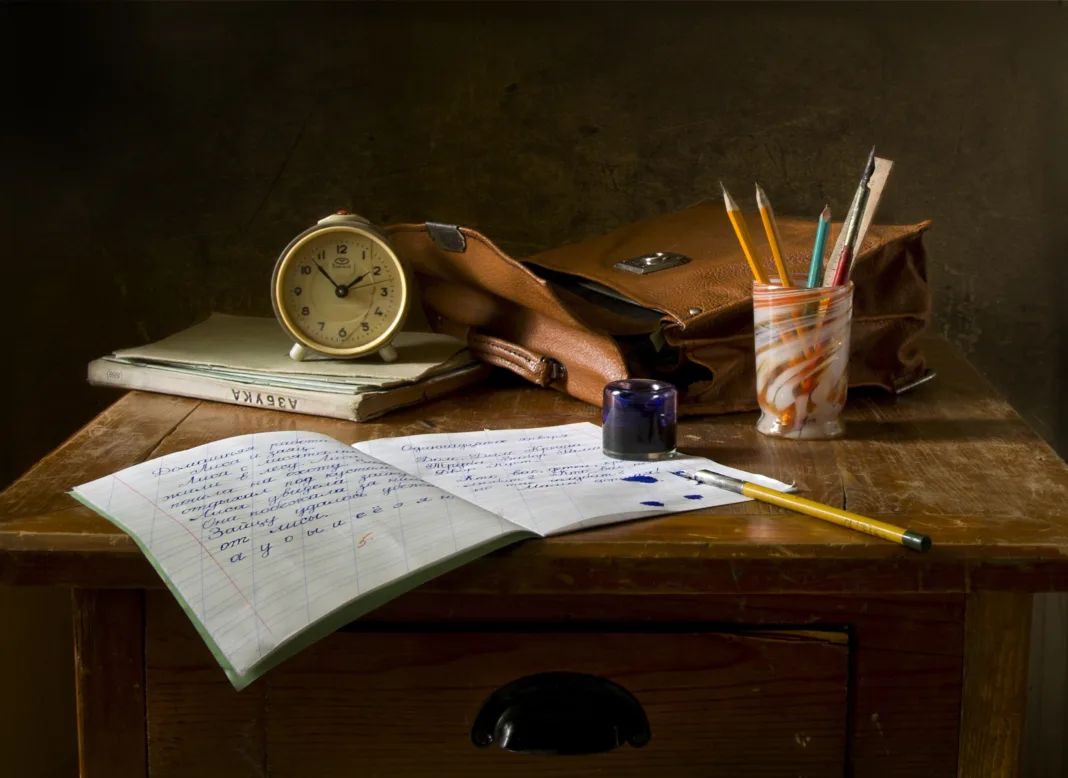

Additionally, you can make lists of tropes you love and parts of fiction you linger over. You might want to look at illustrations or photography that gives you the feeling you’re trying to inspire in your readers. Maybe you’d like making a Pinterest board. Or a playlist. Light some candles. Walk in the forest. Bring a notebook and write longhand. Bring your laptop. Whatever gets the words on the page and the ideas flowing.

And most of all, write for your reader self. Write to please that part of you that picks up some books and sets others aside. Write to indulge all the decadent, weird, macabre joys of your own wicked heart—and you will discover that you’re not alone in the dark.

Holly Black’s The Stolen Heir— a return to the opulent world of Elfhame, filled with intrigue, betrayal, and dangerous desires—will be published by Little, Brown in January 2023.