“One day I was counting the cats and I absent-mindedly counted myself.”

—Bobbie Ann Mason, “Residents and Transients”

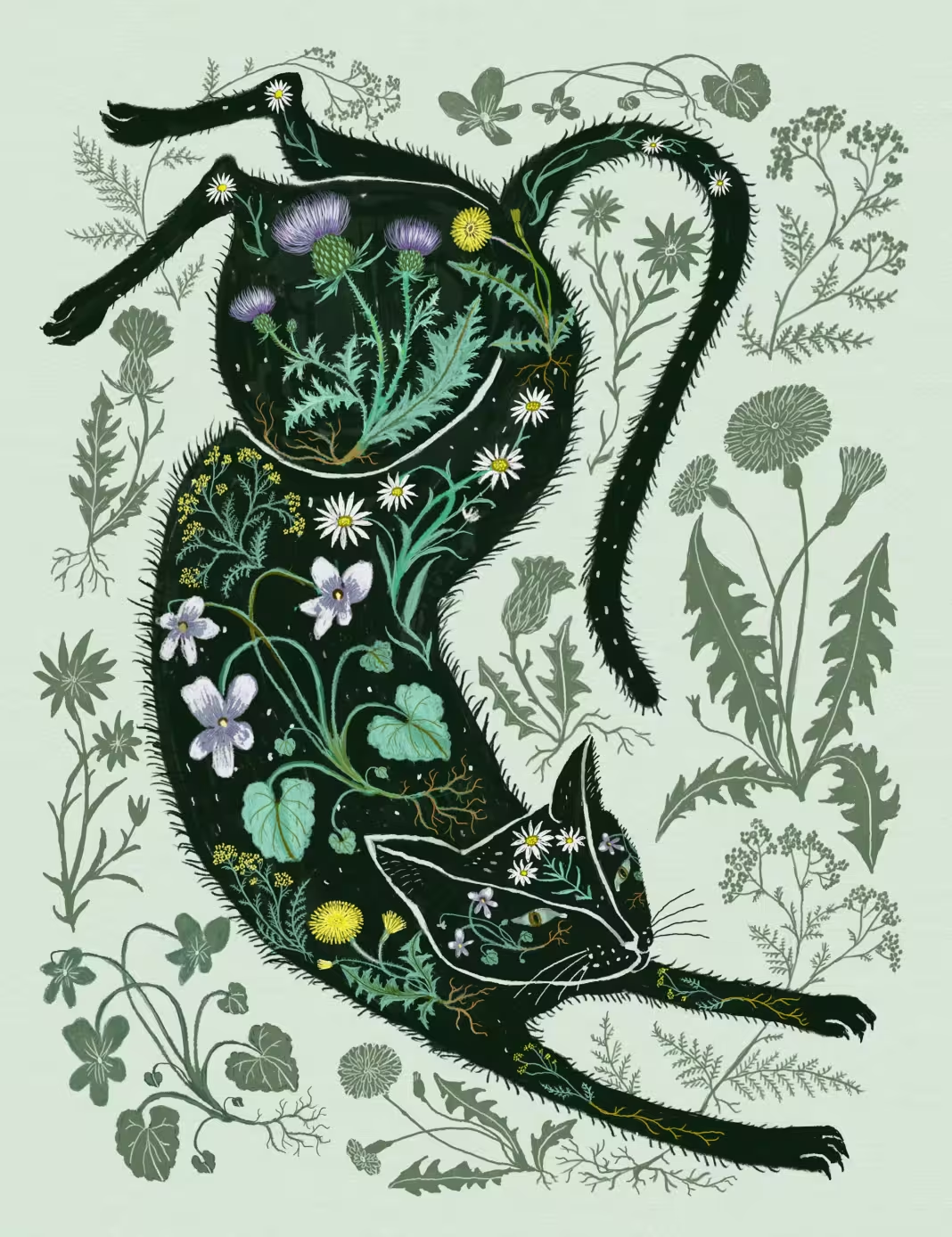

Women and cats have a long history together, an alliance that goes back to at least 2,000 B.C.E. and the ancient Egyptian veneration of the goddess Bastet. Patroness of childbirth and fertility and protector of the home, Bastet is depicted sometimes as a cat and sometimes as a woman with the head of a cat. She’s also believed to be an aspect of the Egyptian lion goddess, Sekhmet, who predates her as a deity. Domesticated cats lived in Bastet’s temple and also in many an Egyptian home, where they were petted and pampered for keeping vermin at bay. To intentionally kill a cat was punishable by death. In the centuries since, for better or worse, the fortunes of women and cats have continued to intertwine.

Cat goddesses appear in other pre-Christian cultures as well. Artemis, the Greek goddess of the hunt, was able to transform into a cat, as was her Roman counterpart Diana. Magically shapeshifting woman cats abound not just in myth and religion but in literature as well. In Madame d’Aulnoy’s “The White Cat” (1698), the titular feline befriends the youngest son of a king, eventually revealing herself to be a beautiful woman. They marry, of course. “The White Cat” has been retold numerous times, most recently in the “The White Cat’s Divorce,” a 2023 short story by Kelly Link in which the cat runs a cannabis business. In George MacDonald’s 1895 novel Lilith: A Romance, Lilith, the first wife of the Biblical Adam, takes the shape of a cat to trick and threaten the novel’s protagonist, Mr. Vane. In film, Jacques Tourneur’s 1942 Cat People tells the story of Irena Dubrovna, descended from the cat people of a Serbian village. As a result of their history of witchcraft, Irena and her neighbors are fated to become black panthers when physically aroused. On a tamer note, in the Harry Potter series, Hogwarts professor Minerva McGonagall has the magical ability to “transfigure” herself into a cat.

Journalist Akanksha Singh notes how often feline adjectives are used to describe women, especially when it comes to sexuality: “Women are called ‘sex kittens’; women ‘purr’ seductively, and are described as having ‘feline’ good looks.” Of course, there are some famous literary tomcats as well, from Puss in Boots to Felix and Garfield, but these characters are more often associated with practical trickery than magic or seductiveness. As scholar Maria Nikolajeva writes, “A tomcat is expected to be adventurous and mischievous. She-cats are … connected to feminine witchcraft, shape-shifting, mystery, and sexuality.”

That is certainly the case with Catwoman, the morally ambiguous sometime nemesis, sometime love interest of DC Comics’s Batman. While Catwoman originated in the comics, she has been played on television and in film by Julie Newmar, Eartha Kitt, and Zoë Kravitz, among others. Unlike her literary and mythic counterparts, Catwoman doesn’t magically transform into a cat at will. Instead, she dons her cat costume and displays catlike, usually non-magical but extraordinarily seductive powers. She is also just simply a woman with an affinity for cat-kind, which places her within a longstanding and sometimes dangerous historical tradition.

While the Egyptian reverence for Bastet elevated the domestic cat in cultural consciousness, women and cats would come to suffer for their connection to each other. Scholar Jody Berland writes, “Women and cats appear across periods and genres as a twosome denoting intimacy, sensuality, and watchfulness inflected with a wide range of dispositions: maternal, sentimental, magical, seductive, and malevolent.” That malevolent image of the woman-cat duo can be traced to the Middle Ages and the widespread Christian belief that cats were emissaries of Satan, intermediaries between witches and the devil. Writer and veterinarian Elizabeth Lawrence notes, “In 1233 Pope Gregory IX officially proclaimed the link between cats and the devil and gave divine sanction for massacring cats, especially black ones.” From the 11th through the 18th century, such superstitions concerning cats, Satan, and witchcraft were prominent throughout Europe. Cats would often be executed with accused witches as their familiars. Lawrence notes, “Owning a cat, especially a black one, was incriminating evidence against anyone accused of being a witch.” Even now, when cats seem beloved throughout the land, black cats are 75 percent less likely to be adopted than other cats.

These superstitions persist in the stereotype of the crazy cat lady, for many a symbol of spinsterhood and lonely, eccentric old age, but devoid of a witch’s supposed magical powers. The most famous contemporary image of the cat lady may be Big Edie and Little Edie Beale, the mother and daughter in the documentary Grey Gardens. The Beales lived for decades in the decaying house of the film’s title, surrounded by cats. “Crazy” cat ladies have also appeared across the television landscape from The Simpsons to CSI.

And yet, in recent years, “cat lady” has become less an epithet and more a badge of honor. Singers like Katy Perry and Taylor Swift proudly use the term, and celebrities from Jennifer Lopez to Martha Stewart and author Alice Walker have been photographed with their cats. There are cat-lady dolls, games, and books as well, all suggesting a humorous reclamation and celebration of a centuries-old bond. Berland notes, “It is not clear whether the special connection between women and cats has been a cause of cat mistreatment or arose in sympathetic response to it, or more likely a combination of the two.” Either way, women and cats are in this together, and somewhere, Bastet is smiling.

Enchanted Living is a quarterly print magazine that celebrates all things enchanted.

Enchanted Living is a quarterly print magazine that celebrates all things enchanted.