“I know a bank where the wild thyme blows,Where oxlips and the nodding violet grows,Quite over-canopied with luscious woodbine,With sweet musk-roses and with eglantine.”—Oberon in A Midsummer Night’s Dream Act 2, Scene 1

Shakespeare’s plays are full of magic: the fairies in A Midsummer Night’s Dream, the witches in Macbeth, the ghost in Hamlet, the spirit-summoning in Henry VI Part 2. Although his work doesn’t necessarily illustrate a belief in the supernatural, Shakespeare often made use of common beliefs about magic as plot devices, turning folklore and written magical tradition into stories his audience would find entertaining.

The magic in Shakespeare’s plays becomes more fascinating when examined alongside the folklore and manuscripts of learned magic that were circulating in early modern England. Historians agree that belief in magic during this period was widespread. It wasn’t only famous occultists and alchemists like the queen’s astrologer, John Dee, who collected these texts, but also other learned people, such as nobles and physicians. Secret grimoires like The Sworn Book of Honorius were rare, but practical magical manuscripts were more common. With the rise of literacy, the charms and healing spells cast by cunning folk and village wisewomen began to be written down too, although elitism and male privilege caused those practices to be viewed by some as lesser.

A Midsummer Night’s Dream, one of Shakespeare’s most fanciful plays, owes much to astrology, folk wisdom, and mythology. The title and setting of the play derive from the legend that the magical powers of flora and fauna were at their highest on Midsummer Night, when the fairies who haunted bluebell forests came out to dance. To a modern reader, Oberon’s reference to “a bank where wild thyme grows” might seem like a throwaway sylvan detail, but thyme, like bluebells, was associated with fairies. According to Richard Folkard’s Plant Lore, Legends and Lyrics, a bank of thyme was a common location for fairy revels. An oil derived from the herb, when rubbed on the eyes, was said to grant second sight. Emily Carding notes

that period herbals and grimoires categorized most of the other flowers in Oberon’s speech—oxlips, violets, woodbine, and musk roses—as being ruled by the planet Venus, evoking the play’s focus on love.

Of course, the most famous magical aspect of the play is the love potion Oberon uses to make Titania fall in love with the next person she looks upon, who happens to be Bottom. The potion is made from a flower Oberon calls “love-in-idleness.” Period herbals list this as a folk name for wild pansy, which was commonly used in love potions of the day. Oberon asks Puck to fetch the flower because he is angry with Titania and wants to play a trick on her. He explains the power of “love-in-idleness” as follows:

The juice of it on sleeping eyelids laidWill make or man or woman madly doteUpon the next live creature that it sees. (Act 2, Scene 1)

After they apply the potion, Titania awakes and falls in love with Bottom, a man temporarily cursed with the head of an ass. It’s worth noting that this “trick” has two male characters give a woman a drug to make her love a man, and that this is played as comedy. The gender politics of A Midsummer Night’s Dream are by far the least charming aspect of the play.

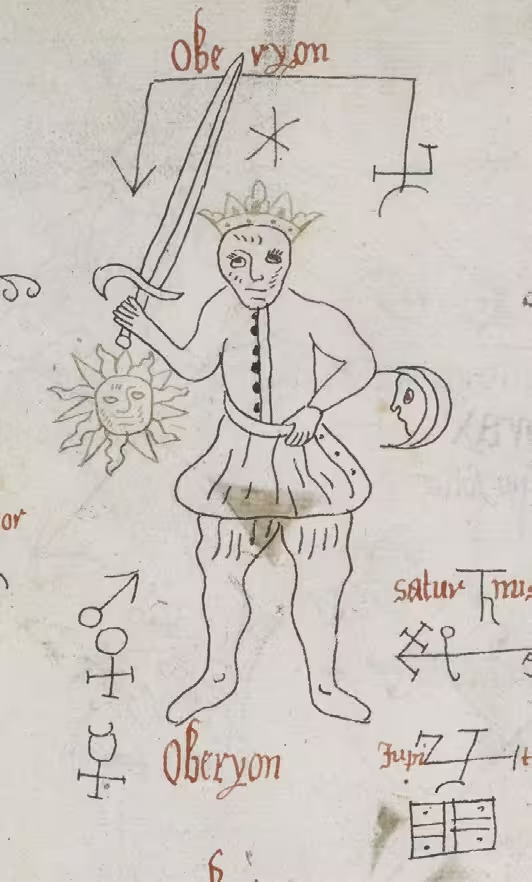

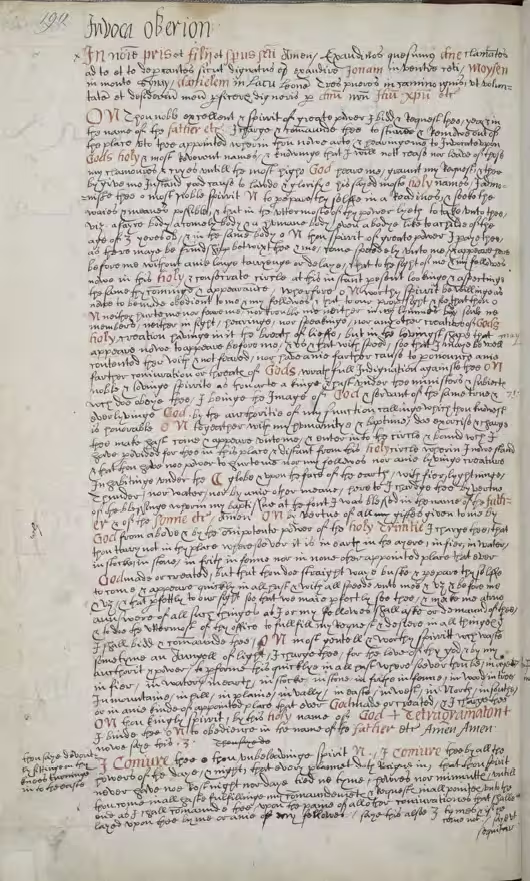

The character of Oberon seems to have been inspired at least in part by a sinister spirit named Oberyon, who is described in several grimoires, most notably a 1583 magical manuscript entitled Book of magic, with instructions for invoking spirits. In this manuscript, Oberyon is described in terms that Shakespeare fans will find familiar:

He teacheth a man knowledge in phisicke and he sheweth the nature of stones herbes and trees and of all mettall. He is a great and mighty kinge and he is kinge of the fayries. (Folger MS Vb26, p. 80)

The manuscript also includes descriptions of a fairy queen and court. The invocation for Oberyon, similar to many spells in medieval and Elizabethan grimoires, reads like a prayer, with repeated references to “God’s most holy name.” It also contains a Catholic profession of faith. This is not uncommon; medieval and Renaissance magical texts are quite religious. Shakespeare scholar Barbara Mowat notes that Oberyon also appears in historical records: A 1444 court case calls him a “wycked spyryte,” a 1510 register “a certain demon.” It may even be possible that Shakespeare’s audience would have been familiar with the name.

Elizabethan England was home to a complex brew of faiths: legally mandated Anglicanism, suppressed Catholicism, and ancient magical beliefs that were being syncretized with both. In Shakespeare’s plays, as in period herbals and grimoires, herbal folklore intermingles with ancient mythology, astrology, and written magical tradition. Suppressed Catholicism admixes with fairy folklore. These traditions, which may seem unrelated today, were not seen as separate. The flower magic in A Midsummer Night’s Dream shows the early modern English belief that everything had a spiritual essence, which was swayed by the celestial circumstances. Physicians consulted an ephemeris (a kind of astrological almanac) before recommending treatment. Alchemists, apothecaries, and village cunning folk believed that the occult properties of herbs, stones, and metals came from the planets.

Everything, everything was ruled by the stars.

Enchanted Living is a quarterly print magazine that celebrates all things enchanted.

Enchanted Living is a quarterly print magazine that celebrates all things enchanted.