Photography: Steve Parke

Photography Assistant: Tedd Henn

Location: Cloisters Castle in Baltimore, Maryland

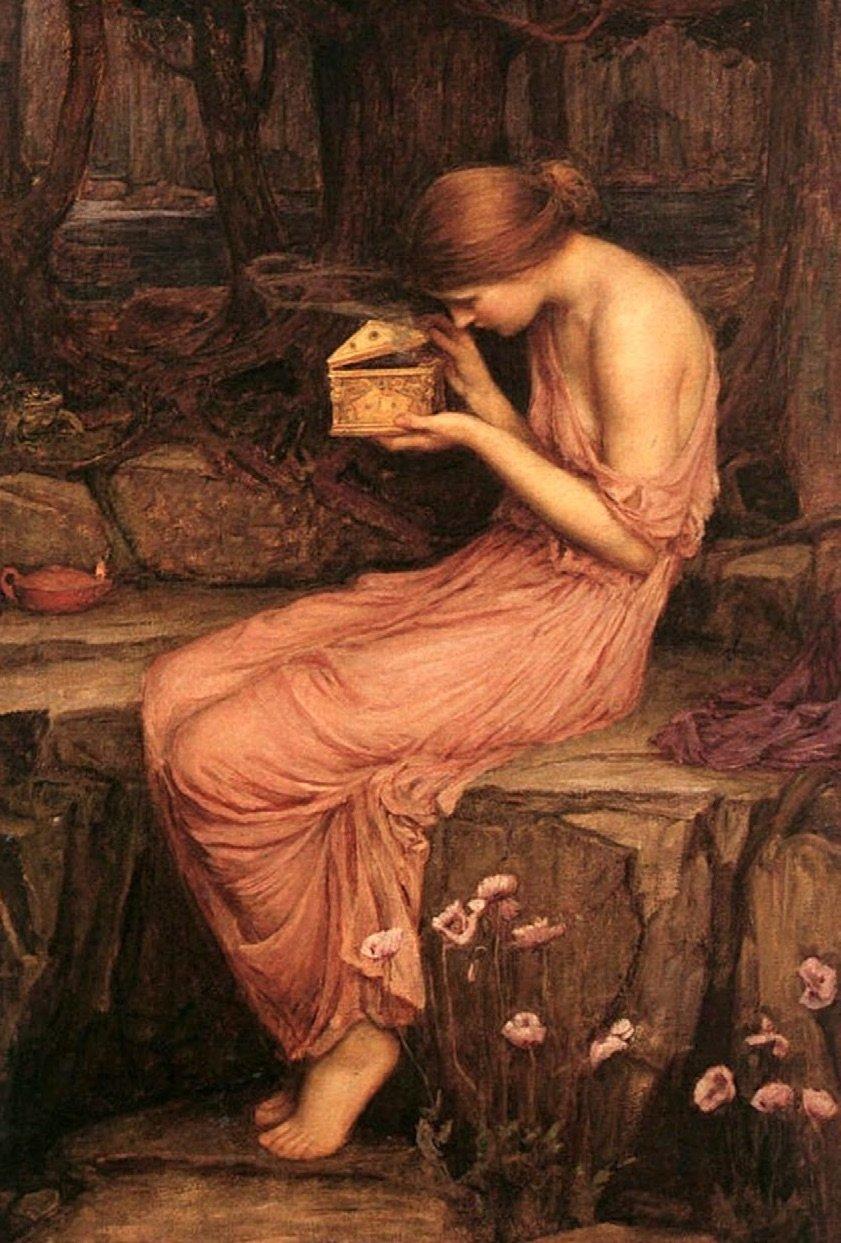

Hair: Nikki Verdecchia of NV Salon Collective MUA: Autumn Shae of NV Salon Collective Clothing: Edye Sanford; Bullseye Clothiers; Emily Kramer Designs; Angela Gavin from Milk & Ice Vintage; Trinket’s Costume and Sundry; personal items from Emilie Autumn, Veronica Varlow, and Kim Cross Instruments: loaned by John DuRant Box on cover: Sue Rawley

I wish all of you could have been there last summer in Baltimore, when I whisked BFFs Emilie Autumn and Veronica Varlow in all their glittering fabulousness from their hotel to NV Salon in the neighborhood of Hampden, where they got glammed up thoroughly enough to embody the spirits of Victorian supermodels Elizabeth Siddal and Jane Morris in our sumptuous cover shoot. As said glamming took place, Emilie gave us all the “trashy beauty parlor gossip,” as she calls it now, about Lizzie and Jane, “which is, I’m sure, what it was at the time they were living.” She told us about the “open affairs”—that is, the “loads of drug use, burned suicide notes, exhumed poetry (and wives), and glorified overactive thyroid glands.” What better way to spend an August morning?

Of course, Emilie knows plenty about these ladies and their time period, which fuels so much of her own art. And by her art I mean her writing, including her novel, The Asylum for Wayward Victorian Girls, and of course her virtuoso violin playing, and the subjects she chooses to sing about—she has released four studio albums, including Opheliac (2006) and Fight Like a Girl (2012), and her worldwide concert tours have featured handmade Victorian-influenced costumes and elaborate, over-the-top stage shows including a troupe of corseted dancing girls, of which Varlow was one of the main attractions.

The shoot took place at Baltimore’s Cloisters Castle, where we lugged pots of roses, racks of clothing culled from various designers and vintage dealers, a few historical instruments, and a stack of inspiration photos I’d printed out the night before. While Emilie wasn’t Lizzie in every shot, and Veronica wasn’t only Jane Morris, they channeled those two superpowers while we scrambled to do as many shots as possible within a few hours, racing up and down those spiral stairs with pomegranates and apples, silver mirrors, old books of poetry, and an endless supply of scarves and dresses slung over our arms. The result is on these pages.

Below, we talk to Emilie more about all the above.

Enchanted Living: Can you tell us about your relationship with the 19th century? Why does this period resonate with you so much?

Emilie Autumn: I’ve always felt that the 1800s are around Elizabethan or even 18th century portraits and think, This can’t possibly have been real—it’s like a fantasy world, or an alternate universe. But we can see ourselves in the Victorians. Certainly the fact that photography came into being during that time doesn’t hurt. But I think we can relate to that time of incredible social and political upheaval, technological invention, and, of course, industrial revolution, because it hasn’t stopped—we’re still in it, racing forward, hurtling onward and wondering what is going to become of it all. Essentially, the Western world became recognizable as the one we now inhabit, complete with the daring idea that we didn’t just hatch on the planet 6,000 years ago as fully developed humans.

So, if you’re a lover of history and a seeker of your roots, the 19th century is where you go to find yourself. If you’re an out-of-the-closet Anglophile like me—I’m full-blown British in my mind—who sincerely doesn’t understand why cravats can’t be an everyday thing, then it is Victorian England specifically. It’s close enough to identify with but far enough away to fantasize about. And that, I think, is precisely why it’s such a great world to tell stories in.

In my novel that really started the association between myself and the Victorian era, the protagonist manifests an alter ego that lives in the Victorian world as a way to process what is going on in her own reality—a sort of therapy through escapism, something I’ve done since I was a child but taken to a literally psychotic extreme. And finally, I should say that it’s a fun world to play in if you have a wicked sensibility because there is a very dark underbelly to the corsets-and-tea-parties culture, as the novel illustrates—London was filthy, diseases were rampant, and women were considered subhuman and treated accordingly. There is little to glamorize, but that won’t stop us from trying and enjoying every minute of it.

EL: Why is this period relevant today? What overlaps do you see?

EA: I suppose all periods are relevant if there is something still to be learned from them, and I do think there is much to learn, particularly from the areas in which we have not progressed nearly as far as we should have. My iPhone camera is amazing, but we are still a global patriarchy.

EL: Can you talk about this shoot? What did it mean to you?

EA: I was truly honored to be asked to represent these iconic paintings. I have loved each of these works since childhood and modeled myself after them to a conspicuous degree for most of my teens and into my twenties. Lizzie Siddal is the reason I originally dyed my blonde hair red at sixteen, parted it in the middle, and proceeded to grow it down to my knees. I don’t believe that anyone who might know of me now is aware of that, so it’s fun to say out loud! This shoot was more than a fantasy come true, it was also a return to a more innocent version of myself, before the corsets and striped stockings and asylums, even if just for a day. It was good to see her again, and I think that a bit of her came back home with me. I am very grateful to Enchanted Living for that.

EL: Do you relate to the women of the Pre-Raphaelite movement?

EA: What is so wild is that when I developed my Pre-Raphaelite obsession as a child, I had no inkling of the truly astonishing stories of these very real women—the world’s first supermodels, some have said—and what their particular kind of beauty meant. I didn’t know that they were very largely ill, extremely poor, and, in Lizzie’s case, fatally depressed. Having learned so much more about Lizzie since, I feel an overwhelming compassion for her. An artist and poet herself, she suffered horribly from mental illness, and it was either ignored or misunderstood to the point where she ended her earthly life at thirty-two. As the subject of mental health is such a dominating theme of most of my music and writing, the connection would be impossible to ignore, and I definitely tried to commune with her the day of our shoot. Not all of the paintings I was a part of re-creating were originally modeled by Lizzie, but she is the one I was channeling.

EL: You’ve written about poetic figures like the Lady of Shalott and Ophelia. What do they mean to you?

EA: Well, the funny thing is that, in my song “Shalott” as well as “The Art of Suicide,” which of course alludes to Ophelia, though not by name, I was writing about Arthurian and Shakespearian characters respectively but was referencing the Victorian painted versions of them in particular. When I was much younger, my passions were medieval history and Shakespeare, and those are actually what drew me to the Pre-Raphaelites in the first place—these Victorian men were painting the women I already loved. Isn’t that bizarre? I hadn’t even really put that all together until just now. I think that I was always drawn to the tragic stories when I was young because they reflected my own melancholy and mental issues but with flowery language and better hair. I saw myself in these characters—they were my pain beautified, and they gave me a gift, inspiring me to intentionally beautify what adversities would come to me as the years went on and life was lived. That is what I still do—it is the basis of my whole career, and it is also the best advice I can share with anyone struggling with anything. Find a way to turn this into art of any kind, because then it is transformed and nothing is wasted.

EL: Can you describe your relationship with Veronica and how you two worked together on your stage show?

EA: The first time I met Veronica, I ran into her arms. We shared a Kit Kat bar and had a mutual vision of our past life where we had been married. (She was my husband and I was burned in a theatre fire, but that is another interview.) Veevers has taught me so much on stage and off, saved my life a few times, and has been a massive part of the best experiences of my entire recorded memory: singing and dancing together for thousands and thousands of beautiful people all over the world. I don’t even know where to go from there. There is love and then there is love. When I learned that we would be working on this ere both powerful muses and in the same tiny artistic circle but not exactly friends—for those who don’t know, Jane always had a thing for Lizzie’s husband, Rossetti, and after Lizzie killed herself, Jane finally got her man—I had this idea: What if some universal consciousness energy engineered this opportunity for these women to reconcile and to even become friends, knowing that they really were all in the same boat, in a really screwed up era, being told how to look and what to do (Get in this freezing bathtub, Lizzie!) just to eat. What if Veronica and I could offer these poor girls a little of our sisterhood? I hope they felt it. And I hope they’re friends. I bet they are.

EL: What does sisterhood mean to you?

EA: Everything.

EL: What inspires you?

EA: Theater. Watching people do things live and making an audience cry and plotting all the wicked ways in which I could do it. Sondheim lyrics. Watching people dance and thinking of how I could transform that movement into a sound and what instrument would it be. Backstage at Phantom of the Opera on Broadway. Sequins. The squirrels in Central Park. Untold stories.

EL: How do you stay enchanted in your everyday life?

EA: I do my very best to exist in the present moment, knowing that the present moment is all there is and all there will ever be. When you begin to grasp this truly, every moment becomes precious and valuable and has potential for magic, because you become very, very grateful. And when you become grateful for life, life becomes grateful for you. If you take in the truth that every moment you experience took 13.8 billion years to create, it’s almost impossible not to feel the magic in that. Also, I don’t go on social media unless I’m posting something positive and then I get right the hell off again, and I don’t use my cell phone as an excuse to not look around at the world I am actually in. Oh, and I promise myself to never fall into the trap of believing that what is on the news represents what is important in the world. It almost never does.

EL: Can you tell us what you’re working on now?

EA: Yes! First, I’ve just gotten in the second printing of my oracle deck called The Asylum Oracle. It is a truly magical spiritual tool that I created to help people (and myself) connect with their own internal wisdom to gain truth and insight, with an emphasis on healing and transformation. What I love most is that each of the fifty cards has a sort of meditation that goes with it, an invitation to really enter another world to bring back the wisdom you need in this one. The Oracle can be found at asylumemporium.com. And second, I am in New York developing the epic musical production of The Asylum for Wayward Victorian Girls. I’m in the midst of orchestrations, and I’m about to go write some oboe parts. The show will be glorious and terrifying and magical, and anyone who wants to follow along with the process and peek behind the scenes is invited to join me on Instagram, where I post loads of the music as it comes together and so much more! (@emilieautumnofficial) This musical is the culmination of everything I’ve done or created up to this point, and I am so excited to share it. It will also be a gift to all the Plague Rats and Inmates who have been with me for so many years and have known and loved the story of the Asylum and made it their own. This show is for them.

I think this website holds some rattling excellent info for everyone : D.

I remember Emilie from her Enchant faerie days. This shoot was such a beautiful hark back to that, I loved seeing this side of her again. Inspired idea!