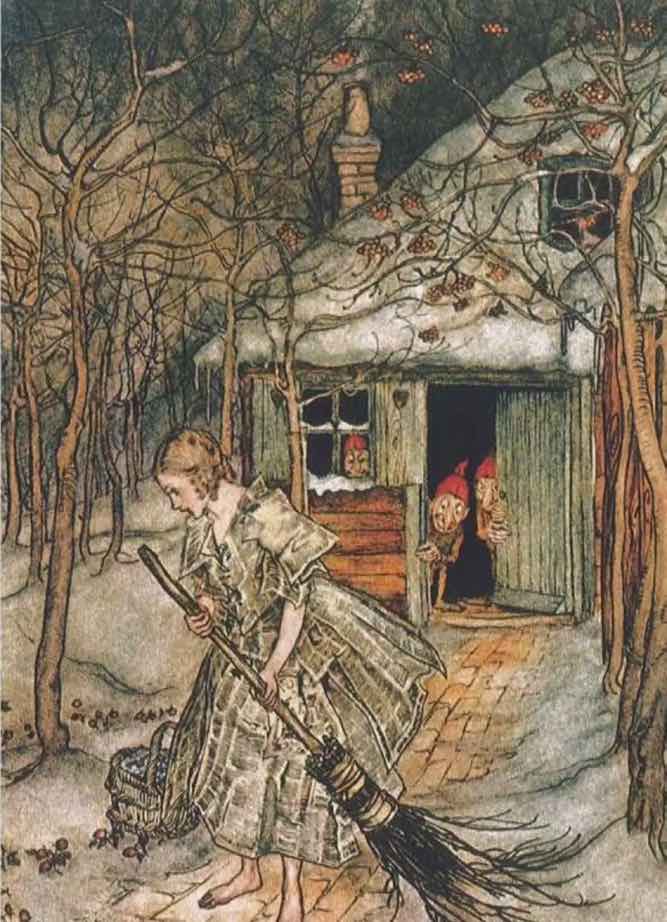

Feature Image:

British Library / Alamy Stock Photo

Rumpelstiltskin (1913), by Warwick Goble

It is night. Darkness has closed in around us as I lie in my three-year-old’s tiny bed and finish casting my words into the cool black so that my ten-year-old in the top bunk can also hear them.

The miller’s daughter has found a way to keep her babe. The frog has turned into a prince. Sleeping Beauty has awakened once more. They do not all end happily, and I do not edit out the gore. Cinderella’s sisters dance in red-hot iron shoes until they fall down dead, the young wife holds Bluebeard’s decapitated head aloft by the hairs of his chiny chin chin, and the boy who lied about the wolves is nowhere to be seen in a sheep-dotted pasture, but there is blood everywhere.

Sometimes the endings are ambiguous: On some nights Little Red Riding Hood’s granny makes it, but on other nights she doesn’t. And both of my boys know that characters like the Baba Yaga or Morgana le Fay are too complicated and layered to be called simply good or bad.

So, stories now all told, it is time for my words to fade, their spell of sleep and protection woven over both children like the holiest of blankets. And I know tomorrow in the brightness of morning, the questions will begin: Why does Rumpelstiltskin want the child in the first place? Why does Sleeping Beauty seek out the spindle? Why would the boy lie a second and then a third time? Why is Bluebeard’s beard blue? And most of all … is it real? Is any of it?

Children like to get down to business. They like play, but out on top of the table, clear play. They sniff out confusion in their elders and will keep at it until it has been fully unearthed and revealed as the interesting bone that it is. So they want to know about the stories—of course they do, they want to know if they are real. To which the only possible and honest response is, What do you mean by real?

I look at what we surround ourselves with today: opinions masquerading as news; metaverse worlds where virtual real estate is bought and sold for astronomical sums; food that looks, smells, and tastes like something it is not; and entire lifestyles predicated on the illusion that everything is limitless. These are a few of the elements that make up reality, the things our little ones are taught to call real. What happens to our accounting of the real when we stack stories—especially fairy tales—against it?

Fairy tales, according to some, started out as diversions from reality. Stories about dragons hoarding treasure, cauldrons that never stop overflowing with food, and magic beans that rise up into the realm of giants were told to make hours of hard labor go by faster or shared as novelties among bored housewives who lacked other outlets for their creative energy. Some of our favorite fairy tales give us storylines of escapism. We find ourselves journeying to the Snow Queen’s Palace, Thumbelina’s flower, or Baba Yaga’s chicken-footed hut. These scenes and locales exist everywhere and nowhere at the same time.

Then there are the stories that play with real locations that were known to both teller and audience: Miles Cross from Tamlin, Sherwood Forest, the mountains in Rip Van Winkle—places where, if the moon is just right and the wind just so, we have the opportunity to fall into something … else. Something uncanny and spooky, something liminal.

We move from the familiar, the known, and the real into the unknown, uncharted, and unreal, right? After all, we all know that those are fairy stories, make-believe, pretend. Except J.R.R. Tolkien didn’t think so. Why, he asks in his essay “Of Monsters and Critics,” do we assume that escapism means turning to something less real? Why can’t escapism be a turning to what is most real? Why is an airplane more real than the Crane Wife’s wings outspread in the snow and under the stars? Why would we ever assume such a thing and give over our understanding in such a way?

“If you want your children to be intelligent, read them fairy tales. If you want them to be more intelligent, read them more fairy tales.” —Albert Einstein

If I tell my children there are no dragons and then we find ourselves staring at an open-mouthed Nile Crocodile basking happily in the afternoon sun, what are they to make of it? Moreover, while there may not be fire-breathing beasts hoarding treasure under great mountains, is there a force of greed in the world so potent that it has the ability to singe the hairs on your arms? I think we know the answer.

There are monsters in stories. Are monsters real? We know the answer to that as well.

Does perpetual lying and deception lead us to be devoured by something at the end of the day? Are looks sometimes deceiving? Can normal, everyday objects hold great power?

What about pluck, courage, kindness, and generosity in the face of overwhelming odds? Are we not learning that forests are enchanted in a way and possess their own intelligence, or that animals have ways of talking, if only we were able to hear them, to listen?

The beloved storyteller Martin Shaw says that parents who tell stories to their children are on the front lines of storytelling. And as anyone who has served on any front line will tell you, that is where the rubber hits the road, where we become very aware of how abstract ideas do or do not inform actual practice. It is here we get clear on what is real and what is not.

It may be helpful for us to recall that the old meaning of “faerie” referred not only to a people but also to a place, a realm of magic and enchantment with which this world, the “real world,” had regular commerce and relationship. When that commerce is interrupted, when the relationship is severed, the effects are seen in this world—in the form of plants and animals dying, in the form of people arguing more and listening less, and in the form of life as a whole becoming harder. At this point the witch, the shaman, the griot, the conjurewoman, the magician, and the storytellers are called on to remake the bridge between the two worlds, to weave them together so that real life can be restored once more. So it is that the roots of our world are sunk into the soil of what some call Faerie.

Much of what these stories show is the most real stuff you will ever encounter. Our kids know it. That’s why they ask for the stories. Tell me what is real, they whisper to us. Tell me a story, they say. And so, we do.