by CAROLYN TURGEON

Photography by STEVE PARKE

Our resident love witch Veronica Varlow calls the legendary Chelsea Hotel the most magical place in New York, a portal that for over a century has drawn the artists, the troubadours, the poets—and plenty of witches too. In fact when Varlow started a secret coven last spring, she knew just where it had to meet. “I think there is no other space that ever had as many amazing artists gathered in one place,” she says. And it doesn’t hurt that there’s an actual pyramid on top. “When you evoke sacred geometry in structures … you invite the magic.”

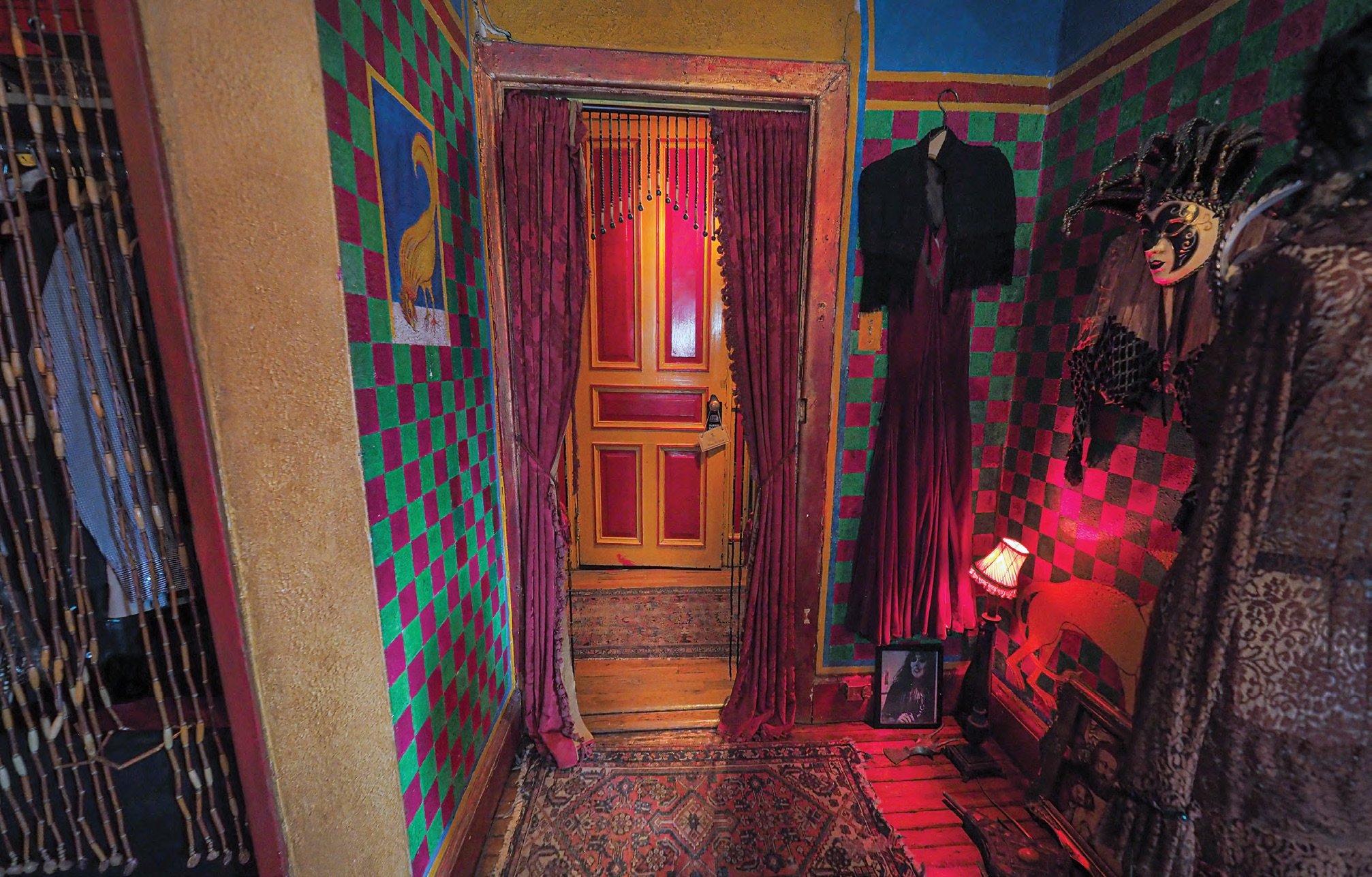

The hotel has been closed for renovations since 2011, and only a few tenants remain—including Varlow’s dear friend Tony Notarberardino, an Australian photographer who’s lived there for over a quarter century in a dreamy, decadent, candlelit space filled with art and color. In other words, the perfect place for a coven. And it’s not filled with just any art but full murals on the walls and ceiling painted by the apartment’s previous resident—and Notarberardino’s friend—the late artist Vali Myers.

Imagine walking into this space for the first time, flowers and patterns bursting from the walls. Notarberardino first visited the hotel in 1994 when he moved to New York; he was meant to stay with a friend, but when he arrived, the friend was living in a tiny room with three other people. After a night out on the town, Notarberardino went the front desk to get his own room for the night and was surprised when the manager offered him a long-term room on the sixth floor. Walking into the painted space brought on a deep sense of déjà vu. Notarberardino realized where he was. He’d seen Myers’s work before, in a “brilliant documentary” called The Tightrope Dancer.

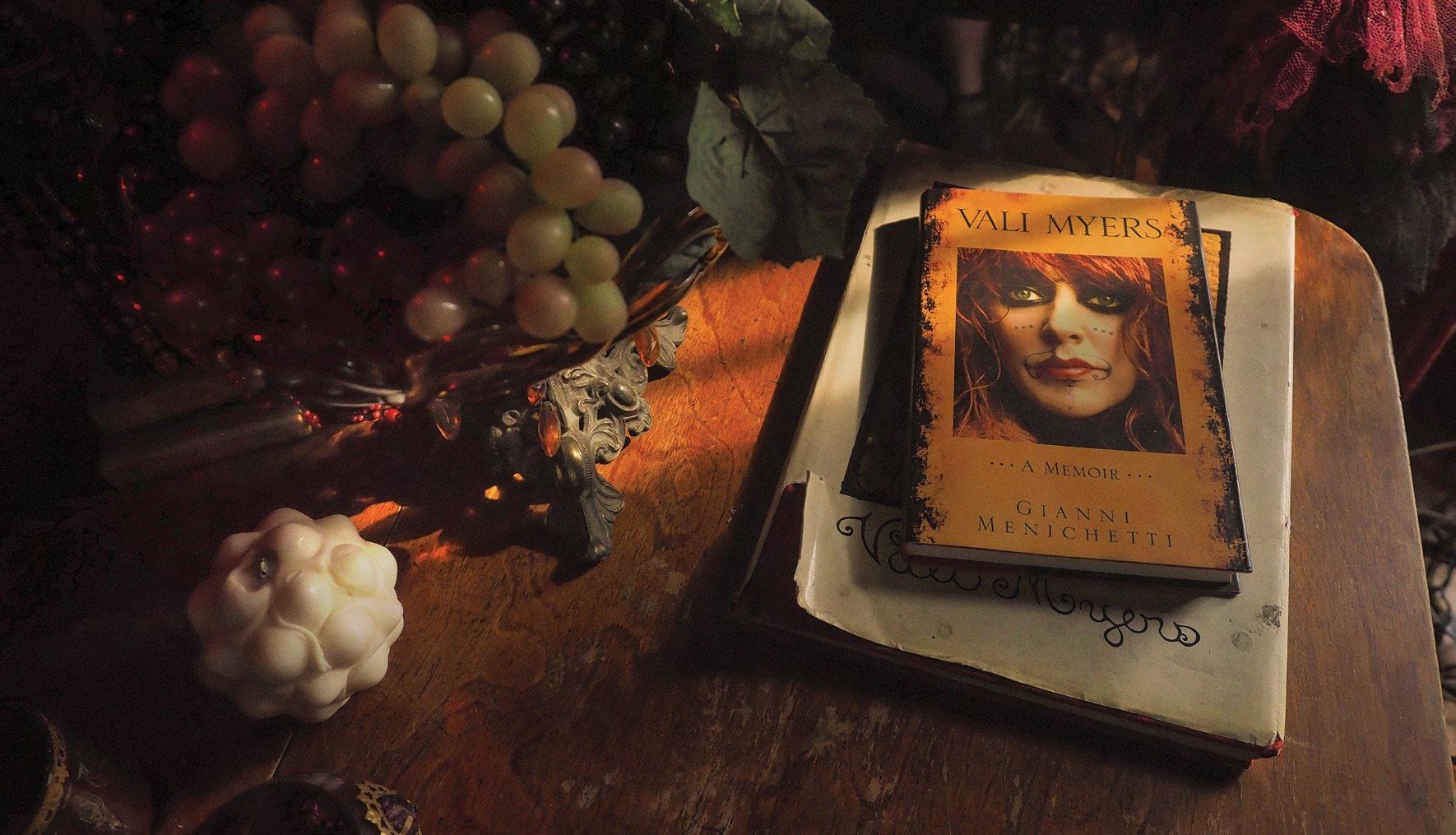

She was no longer there—she, also Australian, returned to her home country in 1993—but her presence filled the space. She was a “supreme witch,” he says now. “She was such a powerful human being, her art so powerful, anyone in her orbit would be sucked into it and attracted to it.”

At the time, Dee Dee Ramone was staying in Myers’s room and Notarberardino in the one next to it. When Ramone moved out, Notarberardino moved into Myers’s room and stayed on—and has been there ever since. Varlow sees him as a mystical figure, an ultra-stylish artist in his own right, always in a fedora— “I don’t think I’ve ever seen him not in a fedora,” she says—who is “the guardian of this space and history and keeps it alive.”

Later, Notarberardino would track down Myers in Australia and they’d become friends, meeting regularly during his frequent Melbourne visits until her death in 2003. Notarberardino took the last photo of her a week before she died. This is what she told a local paper at the time: “I’ve had 72 absolutely flaming years. [The illness] doesn’t bother me at all, because, you know, love, when you’ve lived like I have, you’ve done it all. I put all my effort into living; any dope can drop dead. I’m in the hospital now, and I guess I’ll kick the bucket here. Every beetle does it, every bird, everybody. You come into the world and then you go.”

Of course Myers wasn’t the only to infuse her presence and magic into the Chelsea Hotel, which has hosted a steady stream of artists and geniuses and eccentrics since its doors opened in 1884. In 1997, Notarberardino was returning home at four a.m., standing inside the elevator waiting for the door to close, when “suddenly a female hand with long painted fingernails reached in, blocking the door from closing. In walked an aging drag queen carrying more shopping bags than she could manage and holding the hand of a six-year-old boy.” He decided then and there to start documenting all the strange, beautiful moments he witnessed regularly in this magic portal, and introduced himself. Twenty minutes later he had a finished image—and the Chelsea Hotel Portraits were born.

By now Notarberardino has photographed more than 500 people for the project, everyone from Debbie Harry to Sam Shepard, Grace Jones, Amanda Lepore, Arthur C. Clarke (who wrote 2001: A Space Odyssey), Ron Jeremy, and many more, as well as all manner of transient guests and hotel workers and burlesque stars. “Each portrait stands alone as a true representation of what the Chelsea Hotel really is and means to me,” he says. A book is in the works; you can see some of the portraits on Instagram at @chelseahotelportraits. Each one is stark black and white. It creates an interesting dynamic, Notarberardino says: this “stock harsh reality portraiture emerging from such a magical place.”

Varlow tells the story of how, the day that Leonard Cohen died in 2016, a crowd of mourners gathered outside the hotel wanting to pay homage to the legendary singer. Management would not let them inside, so Notarberardino asked Varlow to go down and invite them all into the hotel—as his guests. And then suddenly his magical space was full of strangers with guitars and memories, and people played his songs one by one, everyone sang, and Varlow even remembers one woman playing a wine glass with a spoon, another raking her fingernails along the blinds to add to the symphony. “It was one of the most beautiful nights I can remember,” she says, “One of those rare New York City moments when everyone comes together. That’s how Tony is, and that’s the spirit of the Chelsea Hotel.”

Above, you can see another bit of captured magic: Notarberardino’s photo of that pyramid sitting on top of the building. The pyramid was “one of New York’s great apartments,” Notarberardino says. The Gothic, three-story structure rose from a private, tree-filled garden in one of the city’s first rooftop gardens, built the same year as the rest of the hotel, in 1884. Over the years it housed Sarah Bernhardt, Arthur Miller, Marilyn Monroe, Jean-Paul Sartre, and Janis Joplin, among others. You can imagine life atop this enchanted building, swirling with all that shared energy, the tangled garden outside your door, all the life blazing up in floor after floor below you.

That was in the hotel’s heyday, of course. Now the outside of the Chelsea Hotel is cloaked in scaffolding. When you enter, it feels half-built; you walk past tape and workmen and peeling walls, tarp covers the floors, and it’s hard to imagine the vibrancy that was once here. Eventually it will reopen, the plan is, as a luxury hotel, and the hotel of old will be gone for good. But right now, at the end of one of those broken halls, is this: a bohemian dream of an apartment, its walls still covered with the visions of a wild, supreme witch who lived 72 flaming years, plus the work of its current inhabitant, who’s made an art of capturing moments in time and who opens his home every full moon to a circle of witches. Which seems only right. “There is a magic about all of it,” Varlow says, “that is unparalleled in the story of New York City itself.”

See more of Tony Notarberardino’s work at @chelseahotelportraits.

Yeah bookmaking this wasn’t a high risk determination great post! .