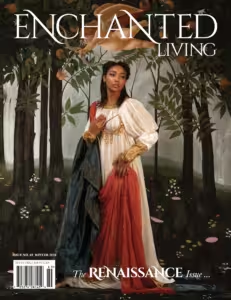

Stephanie Levi-John as Lina from Starz’s The Spanish Princess.

Courtesy of Starz

Why are you going to the Renaissance Faire?” I’ve lost count of how many imes I’ve explained to people that, no, there likely won’t be many other Black people there, but I love it just the same. The atmosphere, the chance to step back in time—there’s a reason Colonial Williamsburg is one of my favorite places. From childhood, I dreamed of far-off places and magical eras; I was enchanted by stories of fascinating lives and beauty.

My love for all things Renaissance and Tudor bloomed early, but I didn’t see myself represented in the books, movies, TV shows, or art of the time. And representation matters. It may sound cliché, but it’s true. When a child never sees anyone who looks like them in the media, it affects them. The media has an impact on the formation of identity, and when you’re not represented, you begin to feel less valuable. It influences your sense of self and how you see yourself in the world.

I’ve always loved the art, creativity, and inventiveness of the Renaissance, but I felt like an outsider—observing from the margins of a story that wasn’t mine. I could read about the era, watch it, even dress up in Renaissance clothing, but it was just cosplay.

I was raised to be proud of who I am and to believe that the history of African people is rich, even if we don’t fully understand the details yet. Deep down, I was always searching for connections. Even when the world seemed to suggest that my story—my place in history—was unrecorded, forgotten, and unimportant, I knew there had to be more to it.

In college, Black history courses opened my eyes. I learned that my ancestors’ lives didn’t begin with slavery and that Africa has a rich tradition of art and creativity. Africans traveled the world long before the arrival of European ships. They were explorers, and like all explorers, they sought a world bigger than their community. The transatlantic slave trade ran at the same time as the Renaissance, and there were Black people in Europe. And, contrary to popular belief, not all of them were enslaved.

John Blanke, for instance, was a royal trumpeter who arrived at the at the English court of King Henry VII in the early 16th century. Records describe him as Black, and we know he was paid twenty shillings for eight days of service in November 1507.

In 1526, when most trumpeters were earning eight old pence a day, he petitioned King Henry VIII for a raise and a promotion to a more senior position, successfully doubling his wages. His portrait is featured in the 1511 Westminster Tournament Roll, a sixty-foot-long scroll of painted vellum— evidence not only of Black musicians’ artistic contributions to European courts but also of his life as a free Black man in 16th century England… a man who understood his value and pursued what he deserved with confidence.

It’s believed that John Blanke may have come to England from Spain with Catherine of Aragon when she was betrothed to Henry’s brother, Prince Arthur.

The television series The Spanish Princess, based on the book of the same name by Philippa Gregory, tells the story of Catherine of Aragon arriving in England with her entourage, among whom is a Black servant and lady’s maid named Lina de Cordonnes. Though there is some speculation that this character is a composite of two Black women in service to Catherine, recorded history is clear only about one woman, Catalina.

Her story begins with capture and enslavement, but ends with her returning to Spain, marrying, having a family, and eventually returning to the home of her birth. She would become an important figure in the investigation of Catherine during Henry VIII’s case for divorce. Catalina would have been present in Catherine’s bed chamber. She would have intimate knowledge, and though it is believed she was questioned, Catalina’s account does not exist. Nor does any information on the end of her life. What is important is that we know Catalina lived a full life, and we know her name.

When a Black actress named Stephanie Levi-John was cast as Catalina, there was backlash and accusations of race-swapping because some people said there couldn’t have been Black women in Europe during that time. Those flawed ideas highlight how deeply misunderstood this history is.

Then there’s Alessandro de’ Medici, my first discovery on this journey to find Black people in the Renaissance. Born in 1512, he is thought to be the son of an enslaved woman of African descent in the Medici household named Simunetta, and Lorenzo de’ Medici, Duke of Urbino. There is also an argument that his actual father is Giulio de Medici, who later became Pope Clement VII.

Alessandro was acknowledged by the Medicis, educated, and ultimately became the Duke of Penne and the first Duke of Florence, ruling from 1530 to 1537. Several portraits of Alessandro exist, depicting him with dark skin and tightly curled hair. Alessandro’s story is remarkable, shedding light on the complexities of slavery and the undeniable role Black people have played throughout world history. Though his rule was cut short due to his assassination, he had two children and a great number of his descendants are still in Europe today. John Blanke, Catalina from Granada, Alessandro de’ Medici—these are figures I wish I’d known about as a child, when I played dress-up in bedsheets with my mother’s white slip on my head, imagining I was royalty with long, flowing hair. I’d always believed there must have been Black people in those magical places, with hidden lives, unseen faces, and voices silenced by history. Now they are silent no more.