Interview by Carolyn Turgeon

Photography by Kyle Cassidy

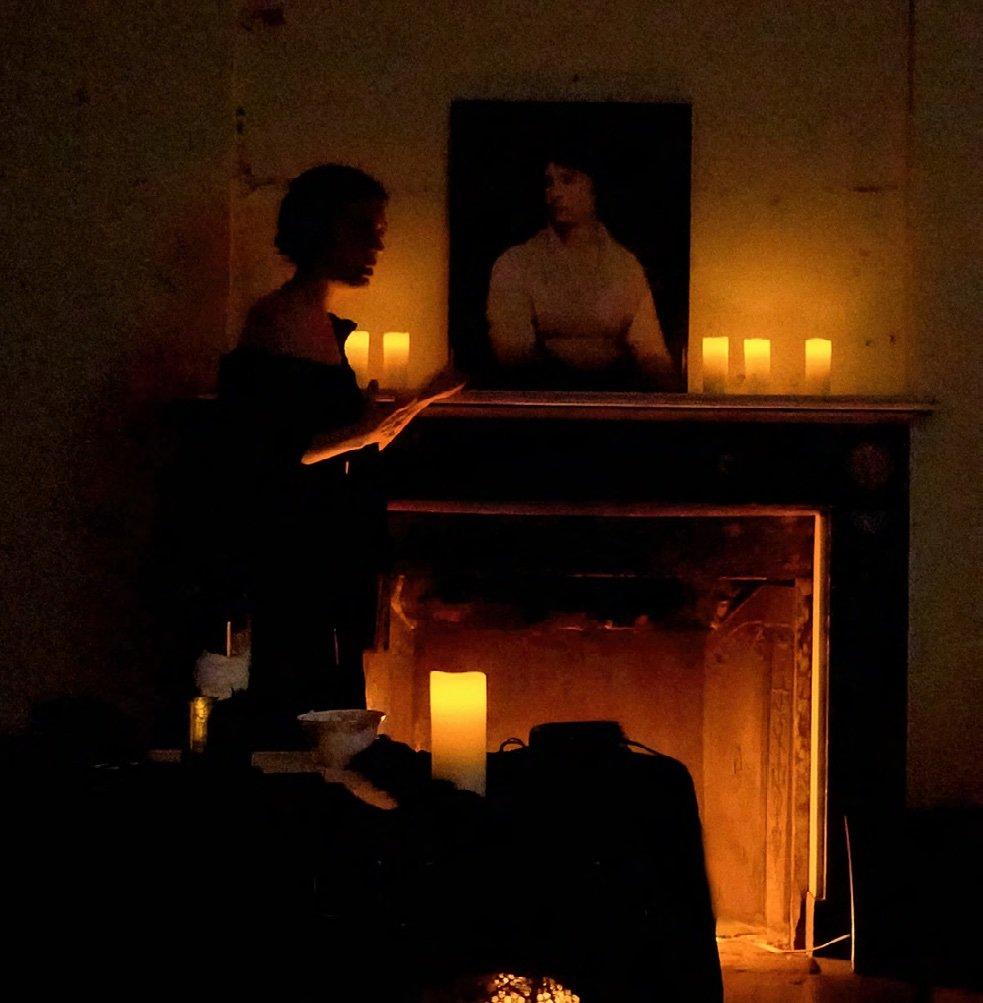

Strange Star Mary Shelley, A One-Woman Show by Jennifer Summerfield

“Don’t leave it to the men to write my story, I beg of you. I saw my mother’s fame defiled by the men who came after. The truth is, men cannot think well of anyone who does not mount on a pedestal and exclaim, ‘When I speak, let no dog bark!’ I cannot do that. It is against my nature; as well cast me from a precipice and rail at me for not flying. No wonder I am reviled. Don’t leave it to them to write my history. They will obliterate me. Who I really was. It’s what they do.” —from Mary Shelley, Jennifer Summerfield

In January 2018, on a candlelit stage at Philadelphia’s Rosenbach Museum and Library, actress Jennifer Summerfield performed her one-woman show, Mary Shelley. It’s the last day of Mary’s life (Shelley died in 1851), and the legendary writer is speaking to her daughter-in-law about her legacy. “Listen to me. Listen to me, my dear,” she begins. “My first impulse is always to befriend a woman.” She talks about her famous parents, her famous marriage, the tragedy and illness that marked her life and that at times subsumed her own astonishing work. Please, she asks the listener, “Don’t let my light go out.” It’s a lovely, emotional homage.

Summerfield says that she fell completely in love with Mary Shelley during her research. Below, we ask her about that process.

Carolyn Turgeon: What inspired you to write about Mary Shelley?

Jennifer Summerfield: Strangely enough, I had originally considered writing a play about Shelley’s mom, Mary Wollstonecraft, one of the mothers of modern feminism and author of A Vindication of the Rights of Woman. Her life and struggles—as well as her beautiful travelogue, Letters Written During a Short Residence in Sweden, Norway, and Denmark—have always filled me with admiration. But as with any complex, gifted thinker, the question of how to approach her story and distill it into a one-woman performance held me in check.

Then, when Philadelphia’s Rosenbach Museum and Library was planning their programming for the 200th anniversary of the publication of Frankenstein, their manager of public programs, Edward Pettit, approached me about creating a piece on Mary Shelley. The performance accompanied their special exhibit, “Frankenstein and Dracula,” which had the original manuscripts of both novels on display.

Edward had known my work for many years and had helped me in 2012 when I was researching the role of Lord Byron’s daughter, Ada Lovelace. He’s an incredible resource for all lovers of Victorian and Romantic literature, and the Rosenbach Museum houses many of the original manuscripts of the Romantic era. It’s thrilling to have a place here in Philadelphia where you can be alone with the words of the world’s most celebrated writers. Being able to research Mary Shelley and her circle at the Rosenbach was such a gift.

CT: Did you learn anything about her that surprised you?

JS: Mary Shelley was practically a blank slate for me. I think, like many people, I always underestimated her, thinking she had peaked so early, writing Frankenstein at nineteen and then apparently devoting the rest of her life to the work of her deceased husband, poet Percy Bysshe Shelley. When I discovered all the sorrows and setbacks she overcame and that her life was much more than Frankenstein and keeping her husband’s flame alive, I came to deeply appreciate her. She was every bit the champion of living life authentically and helping the downtrodden that her mother was. She had a strength and integrity that I admire. She was also an incredibly prolific writer, not only of novels and poetry but biographical articles for the Cabinet Cyclopaedia. She was constantly hunting for the next subject to focus on, in large part because she had only herself to rely on.

I didn’t realize what a complicated relationship she had with her father, philosopher William Godwin. He had come into his fame as a free thinker, writing works such as An Enquiry Concerning Political Justice, which the later Romantics held up as a handbook on how to live and love freely. And his own relationship with Mary Wollstonecraft followed this approach. They had separate households, didn’t marry until Wollstonecraft was several months pregnant with Mary, and then were embarrassed about it because they felt they had sold out and their fellow philosophers would laugh at them. However, what surprised me is that by the time Mary was a teenager, Godwin had become conservative in his beliefs and disowned her for trying to live life as freely as her parents had a generation before.

It was surprising to me how the 18th century salons that Mary Wollstonecraft attended and that were led by incredibly educated and worldly women in England and France were so far ahead of the world Mary Shelley later lived in. The world had turned backward in twenty years, which we see even today. Great progress is made in one generation that is then somehow lost, through political and societal upheaval, in the next generation.

Another thing that astonished me was that as Mary Shelley moved into the Victorian era as a widow and single mother and felt pressure to appear respectable, behind the scenes she was just as “shocking” and ahead of her time as always, befriending and championing women who were living on the fringes of society and even assisting in a lesbian wedding and helping the newlyweds flee England. Just amazing!

CT: What were the challenges of writing about her and speaking in her voice?

JS: There were so many challenges. I quickly realized that it would be possible to write a dozen plays about her and that because it was only an hour in length, each one could focus on a single aspect of her life. I wrote several drafts and kept having to sacrifice people and events that I found personally fascinating but that didn’t have a place in this iteration of the piece. My friend, director and playwright Cara Blouin, helped me in the early development stages and came up with the device of speaking directly to my daughter-in-law and seeking her help, which I found incredibly useful, just to give it a specific focus. The main challenge was in giving it a certain theatricality while still sharing her story.

I am still haunted by the pieces of her story that had to be discarded this time around, and I would like to return to her when I have more distance, approaching her life from a different angle.

Having read so much of her writing, including private journal entries, there are many seeming contradictions in her life and her sense of self. I think that’s true of anyone who keeps a private journal. There’s the face we show the world, the discussions we have with intimate friends and family, and then those private, often disjointed thoughts that we don’t even know we have until we see them on the page in front of us. It made finding a voice for her in this show an added challenge.

I ended up focusing on some of her more complicated and fraught female relationships, because there was a sense throughout her life of having been betrayed or deserted by the women she was closest to. But it’s definitely not the whole story.

CT: Is there anything from this experience you still carry with you?

JS: Researching and writing about Mary Shelley has made me feel a deep connection to her. At one point, in order to gain a clearer understanding of her complicated family tree, I created a tree on ancestry.com, and I have a sense that there’s a missing branch that I’m on, another half-sister to be swooped along on one adventure after another.

I’ve always loved doing research, but this experience has taught me more than any other not to fall into assumptions, to know that there’s always another side to the story, which I hope has made me more empathetic in my general approach to people and their sometimes incomprehensible actions.

CT: Do you identify with her, or with the Romantics generally?

JS: My love of nature is heavily influenced by the Romantics. My happiest places have always been walking in the woods, sitting on a rock overlooking the sea, finding solitude and companionship through communing with nature. And I thrive on travel. Their love of travel, particularly through the ancient world and Europe, fed their creativity. When I was beginning the writing process, I was house-sitting in Paris, and I imagined I would sit in the courtyard of the house, drinking café and du vin and whip out a draft. Needless to say, I was too busy exploring the banks of the Seine and walking in the woods outside the city to do much work. But it was all percolating.

The Romantics were also obsessed with death, and particularly early, tragic death. And whenever I’m in a new place, I always search out the nearest cemetery. My favorite place to walk in Philadelphia is our local Victorian cemetery, also a favorite of local bird-watchers. Mary and her future husband, Percy, had their first romantic rendezvous at the grave of her mother. Creepy, but very Romantic.

CT: In what ways would you say that you and your husband Kyle live as modern Romantics?

JS: The Romantics always depicted themselves as lovers of solitude, but Mary and her circle were quite social beings, surrounding themselves with fellow poets and painters, often times sharing their home with poet friends who needed a place to live. Kyle and I love hosting artistic gatherings where someone sings and someone else reads a selection from their new book. Kyle’s artistic collaborations often remind me of the collaborations the Shelleys had with other writers, getting inspiration from a friendly challenge.