Early morning. Sea mist still hovers over the water, and the bracken-covered dunes that furl out beneath my feet like a green carpet are alive with activity. Under the surface are cool, sandy-walled tunnels and dens filled with breath, scale, and rattle—dunes in south central Texas are known to be preferred dens for rattlesnakes. On the surface amid the succulents stands a blue heron—awkward, gawky, royal. Skittering across those dunes are translucent sand crabs that would fit in the palm of my hand. One produces a rapid series of annoyed castanet clicks, not with its claws but with its jaws, when we fish it out of the chlorine-saturated pool and return it to its sandy home.

We have come to the ocean—really the Gulf of Mexico—my family of four, on what has become a yearly pilgrimage of sorts. Our extended family makes its way here each Easter. We are a motley assortment of Catholics, Baptists, witches, and wanderers gathering at the edge of the land, the edge of our place, to behold resurrection, life returned once again. While here we rub up against each other, swapping stories and scent, trading silences and tears. We note the ones that choose to show up, honor the ones who cannot, and bless the ones that won’t. We return to lineage and family pattern here, return to pack, re-establish our North Star.

But this year I am not alone. I’m carrying prayers with me from my other family, the whole and hearty community of soulful seekers that I have been charged and privileged with stewarding over the past ten years. These are specific prayers being made. Prayers for healing, restoration, and resurrection. I take the prayers down to the gray water’s edge and sing them over the waves and into the sea. I rock back and forth in time with the waves lapping against the shore, sending out the sacred smoke. I steal away to fill glass jars with ocean water, shells, handmade oils, and petitions for deeper-than-deep healing, recovery, releasing of addictions, petitions, and prayers for returning to life. More sacred smoke for blessing and consecration, sealing the jars with breath, fire, and melted wax, and then it is time to gather them up, tuck them between the towels and sunscreen, and carry them home. The prayers remain here at the ocean’s edge, carried by the endless, rocking waves.

Back up on the balcony in the wee hours of the morning, I watch Venus, a luminous teardrop, hanging over the wide blue breast of the sea. The moon is full but Venus’s light is bright enough to rival Luna’s. The dunes and the strip of beach have changed even in my lifetime, growing narrower, smaller, closer to being taken over completely by the foamy hem of deep blue dress. More sea, less sand. More depth, less space. I know the causes; I understand the flux, the moment of change we are in and we are. I know that in the lifetimes of my bright, beautiful boys, it will change even more. And I know it is not the first time.

South central Texas going all the way down to the Gulf of Mexico looks today like a series of rocky hills, flat farmland, vast ranches, and limestone creeks and rivers fed by deep underground springs. But 260 million years ago, long before the dinosaurs and even before the Pleiades, Texas existed under a vast and ancient ocean. It’s why it is relatively easy to go for a walk in the part of the state where I live and find ancient fossilized clamshells, fishbones, and coral. These ancient seas receded; landmasses changed. You would never know that the whole state had once been the bottom of an ocean floor. Now it is beginning to happen again; as tides rise, bits of land are covered in the foamy brine.

The ocean or sea is one of the most oft-invoked images to describe change. The tides, current, and even color of the ocean change not just from day to day but from moment to moment. I sit on the deck of the beach house we’re staying in, sipping my coffee and watching the show. Gray skies are met by slate gray waters. But then a shaft of sunlight pours down and illuminates the depths, summoning a clear cobalt to come out and play.

It is still one moment, calm enough for my three-year-old to wade out bravely into the shallows, watching the little angel-wing clams tuck themselves into the wet sand, and then powerful enough in the next moment to knock him down. The undertow of the Gulf of Mexico is particularly notorious for this. Things look calm and swimmable on the surface, but those deep and unseen currents have lifted more than a few souls up and off their feet, carrying them too far from shore to swim back, too far to be saved.

We are taught as little children that should you venture too far out in the water and the invisible hands of the undertow grab onto your ankles and carry you off, you must not ever swim against the current or tide. This will exhaust you and exhaustion leads to death. Instead, we are taught to grow still, catch a breath, find the current, and then swim with it, swim parallel to the shore; this will help you find purchase once again. It is perhaps due to invisible forces like undertows that ocean and sea are also often metaphors for a different kind of power, a unique type of force. The North Star, by contrast, not to mention a number of constellations, provide something certain, definite. They are solid, gleaming marks by which you can set your sights and chart a course. They are the constants against the backdrop of the ever-changing sea. On the other end of things are the iron anchors. Drop them and they kick up silt on the ocean floor, dragged along until they grip onto something. Locked into place, they hold a ship fast, keep it still and safe.

It might seem then that prayers sent out over ocean, songs and stories and petitions carried off by waves, have nothing fixed about them. They are adrift. But prayers and songs and stories have been prayed and sang and told not just of the ocean but to the ocean for millennia, as long as there have been creatures to pray, sing, or tell a tale. Early in the morning, on just the other side of a full moon, I look out to the sea. Vast white wings suddenly cut through the air along with a throaty call. An owl is hunting over the night dark dunes, flying parallel to the ocean’s edge. The waves come in and out, lapping at the land, caressing it with their glassine hands.

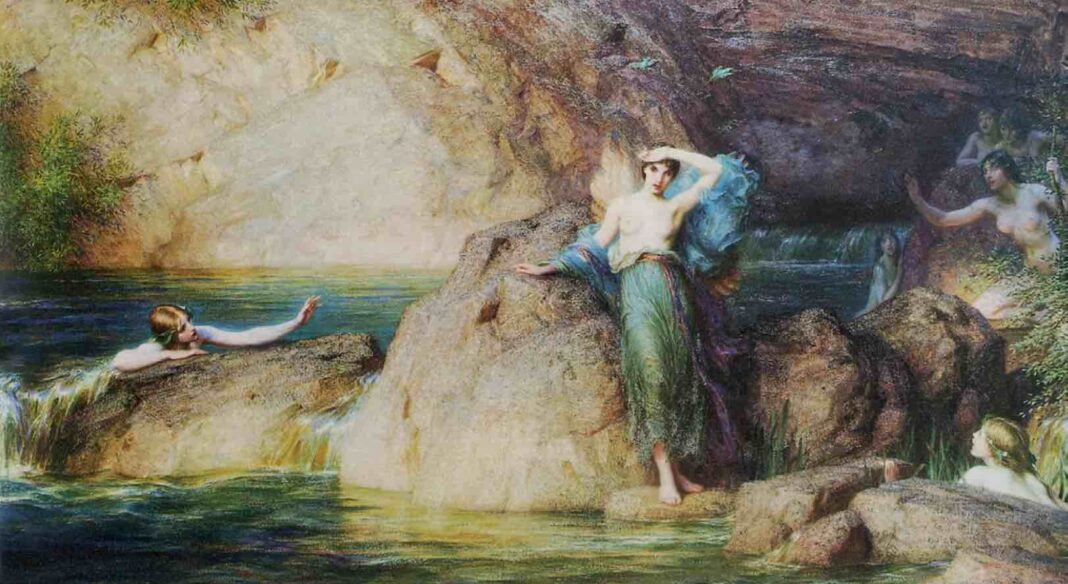

I think of every holy figure I know of who is associated with the sea. Tiamat, Aphrodite, Venus, Sedna, Y’maya, Namakaokahai, Chalchiuhtlicue, Stella Maris, Morgan le Fay … the list goes on. Each with their own stories and tales and dramas but also sharing in something vast and deep and ever flowing. Perhaps not such a bad place for prayers, after all. I look out over the ocean, remembering that once, not so very long ago, it covered the land where the beams of the porch I’m standing on right now are sunk deep. I understand why the sea is the image we reach for when we need to describe shifts and change. But listening to the waves as they keep perfect time, I feel that perhaps it is the most eternal thing of all. No wonder we carry prayers to it, call out wishes over it, still.