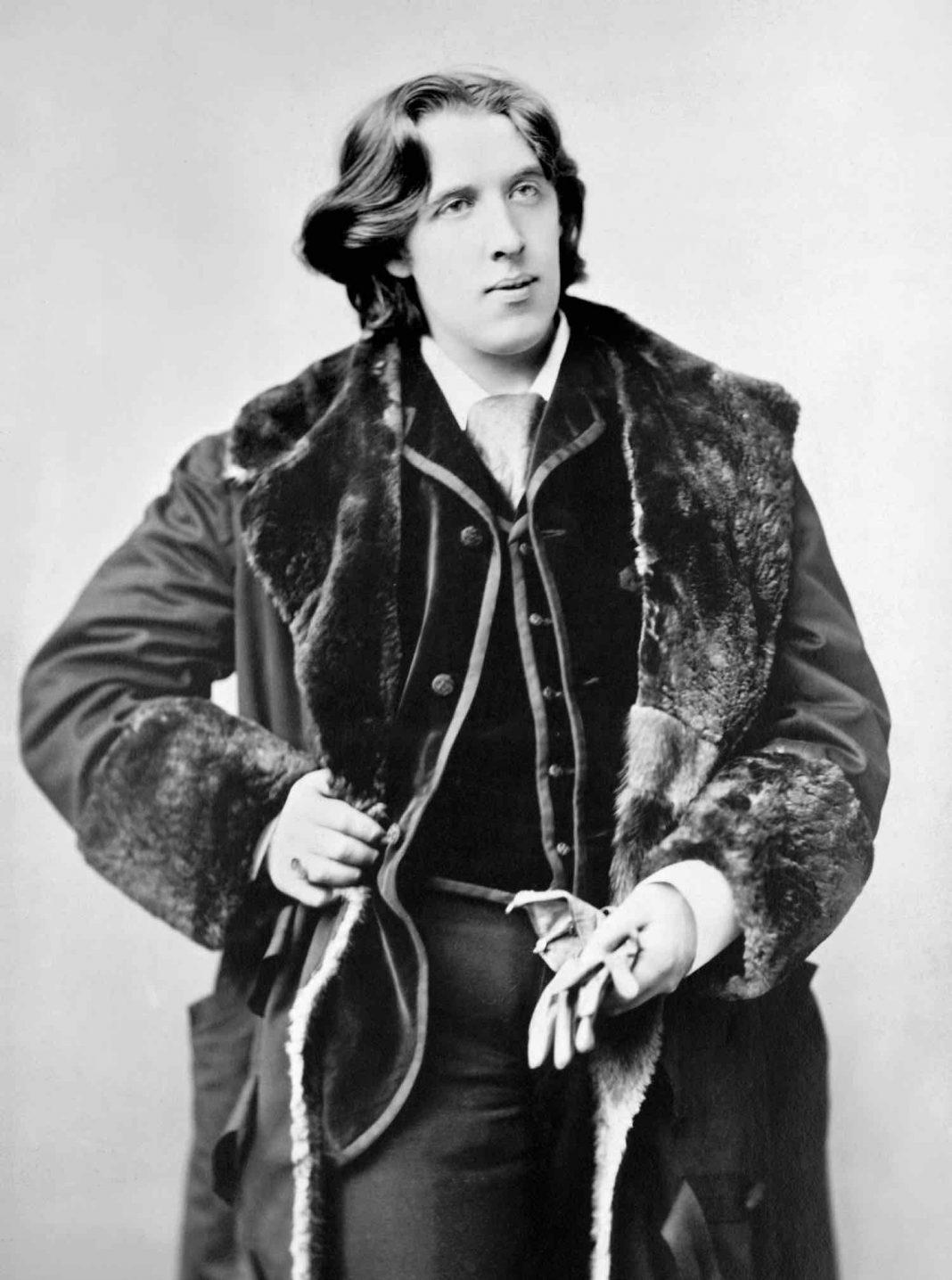

Portrait of Oscar Wilde (1882), by Napoleon Sarony

IanDagnall Computing / Alamy Stock Photo

If we were in Paris (we really should be in Paris!), I would say, “Let’s buy cups of steaming hot chocolate and flaky, buttery croissants at our neighborhood café, then take métro line 2 to the 20th arrondissement and visit Père Lachaise cemetery.” There we would find the tombs of famous writers, artists, and musicians like Molière, Eugene Delacroix, Frédéric Chopin, Georges Seurat, Marcel Proust, Colette, Edith Piaf, Gertrude Stein, Max Ernst, and Jim Morrison. But the most magnificent tomb belongs to the Irish writer Oscar Wilde.

The tombstone is decorated with a winged angel, in a modern style inspired by the Assyrian statues in the British Museum. Since 2011 it’s been surrounded by a glass wall to keep visitors from kissing the stone and leaving lipstick marks. Before the glass wall was erected, so many visitors would come and kiss the stone or write messages on it like “Wilde child we remember you” and “Keep looking at the stars,” that it started to disintegrate.

Who was Oscar Wilde, and why does he inspire such devotion a hundred years after he died, desperately ill and penniless, in a Paris hotel room? During his lifetime, he was alternately mocked, fêted, lampooned, and called one of the most dangerous men of the age, a harbinger of modern degeneration. He was the author of some of the most celebrated plays ever written, including The Importance of Being Earnest and the symbolist extravaganza Salome, considered so scandalous at the time that it could not be performed in England. Instead, it premiered in France and became the basis for the Richard Strauss opera. He also wrote lyrical, poignant fairy tales like “The Happy Prince” and “The Nightingale and the Rose.” But it was his novel The Picture of Dorian Gray that most scandalized 19th century British society and brought about his downfall. It also ensured his literary immortality.

Wilde was born in Dublin to the famous eye and ear surgeon Sir William Wilde and his wife, Lady Jane Wilde, who was a passionate Irish nationalist and wrote on political topics for pro-independence newspapers under the name Speranza, Italian for “hope.” Both she and her husband were interested in native Irish folklore and literature; when William treated poor patients who could not pay his fees, he would ask them to pay in stories. After his death, Lady Wilde published Ancient Legends, Mystic Charms, and Superstitions of Ireland, with a final chapter by her husband, which is still available in a Dover edition. Politics, literature, and the scientific issues of the day were all discussed at the Wilde dinner table. The young Oscar grew up in this intellectual and literary milieu, excelling at school and eventually going on to Trinity College. He won a scholarship to study classics at Oxford, and that is where his unusual ideas about art and society first gained attention.

Imagine a young man walking toward you on one of the hallowed paths of the oldest and most prestigious university in England. His long hair is blowing in the wind. He is not yet dressed in the Aesthetic fashion he would later recommend, but his head is filled with subversive ideas. He has been reading the art criticism of Walter Pater, especially the final chapter of Studies in the History of the Renaissance, in which Pater tells his readers to experience everything—to burn with a “hard, gemlike flame” because we are all too soon snuffed out. This was not the sort of philosophy that staid, respectable Victorian society looked upon with approval. Pater removed the conclusion in the second edition because he thought it might mislead his readers, and then reinstated it in the third edition. But the most important message of his book was the idea that art should exist for its own sake—l’art pour l’art, in the words of French Aesthetes like Théophile Gautier. Art did not need to serve a moral purpose, as Victorian society assumed. It could exist simply on its own terms, for the sheer sensory pleasure it gave us. Wilde was influenced both by Pater’s philosophy and the teachings of John Ruskin, who was associated with the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood and espoused radical ideas like education for the working classes. If you stopped Wilde in his perambulations, the long-haired young man might invite you back to his rooms, decorated with objets d’art, peacock feathers, lilies, and blue porcelain imported from China. He reportedly once told a friend, “I find it harder and harder every day to live up to my blue china,” and the phrase was satirized in the popular magazine Punch, which was beginning to mock what it considered effeminate Aesthete young men and their counterparts, masculine New Women who agitated for rights such as the ability to ride bicycles or attend college.

Wilde graduated from Oxford with honors but did not get the fellowship he applied for, and the woman he loved, Florence Balcombe, married fellow Irishman Bram Stoker, who would later write Dracula. Determined to make a name for himself, he moved to London and embarked on a literary career. Living on money from a family inheritance, he began to publish poems and started writing his first play, Vera; or, the Nihilists. Then, unexpectedly, he was invited to go on a lecture tour in the United States. Lectures were a popular form of entertainment in the 19th century—Charles Dickens had made a small fortune on such a tour, and Wilde was eager to follow his example. The subject of his lectures was to be Aestheticism, popularized by the satirical Gilbert and Sullivan operetta Patience. Wilde arrived in the U.S. as a living embodiment of the Aesthetic movement. The New York World described his appearance on his arrival in 1882:

Mr. Wilde is fully six feet three inches in height, straight as an arrow, and with broad shoulders and long arms, indicating considerable strength. His outer garment was a long ulster trimmed with two kinds of fur, which reached almost to his feet. He wore patent-leather shoes, a smoking-cap or turban, and his shirt might be termed ultra-Byronic, or perhaps—décollete ́. A sky-blue cravat of the sailor style hung well down upon the chest. His hair flowed over his shoulders in dark-brown waves, curling slightly upwards at the ends. His eyes were of a deep blue, but without that faraway expression that is popularly attributed to poets.

Trinity College and Oxford University

The young man from Oxford had become a fully formed, appropriately dressed Aesthete. Although the newspapers caricatured him mercilessly, sometimes in anti-Irish terms, the lectures were wildly popular. He spoke to Americans on subjects such as home decoration and artistic dress, arguing for the importance of art and urging them to beautify their surroundings. Critics worried his radical ideas would unduly influence—and potentially corrupt—the populace.

Unfortunately, Vera was a flop, but back in London, Wilde continued writing plays. He also met and married Constance Lloyd, the daughter of a prominent barrister. The next ten years were a whirlwind of writing, social events, and family life. The Wildes had two children, Vyvyan and Cyril, and Oscar’s plays found large audiences. Lady Windermere’s Fan, A Woman of No Importance, and An Ideal Husband were all popular hits. He continued to court controversy with his articles and essays, which argued for liberal social causes as well as new ways of looking at art and the responsibilities of the artist. He and his wife entertained lavishly, inviting important artists and intellectuals to their house at 16 Tite Street, including his close friend James McNeill Whistler. Whistler had been experimenting with exactly the sort of art for art’s sake that the Aesthetes valued. His painting The White Girl, of a red-haired young woman in a white gauze dress standing on an animal pelt, had been rejected by the Paris Salon because it was too radical a departure from conventional techniques. It did not help that the model, Joanna Hiffernan, was his mistress. Later, he renamed the painting Symphony in White, No. 1 to emphasize that viewers were supposed to look at the painting as a painting, not a representation of the model.

At the same time, Wilde was living a secret life. His friend Robert Ross had become his first male lover, and Wilde had started to explore his own sexuality. Then, in 1891, he met Lord Alfred Douglas, known as Bosie. It is ironic that Wilde did not meet Bosie until after The Picture of Dorian Gray was published in 1890, because Bosie was Dorian brought to life—young and beautiful, although without Dorian’s initial innocence. Even if you have not read the novel, you probably know what it’s about: a young man who wishes that he could always stay the same age, and his portrait, which ages instead of him. When we first meet Dorian, he is in a perfect Aesthetic interior, the studio of artist Basil Hallward. There, among the “rich odor of roses” and “heavy scent of the lilac,” we meet the charming and seductive Lord Henry Wotton:

From the corner of the divan of Persian saddle-bags on which he was lying, smoking, as was his custom, innumerable cigarettes, Lord Henry Wotton could just catch the gleam of the honey-sweet and honey-coloured blossoms of a laburnum, whose tremulous branches seemed hardly able to bear the burden of a beauty so flame-like as theirs; and now and then the fantastic shadows of birds in flight flitted across the long tussore-silk curtains that were stretched in front of the huge window, producing a kind of momentary Japanese effect, and making him think of those pallid jade-faced painters of Tokio who, through the medium of an art that is necessarily immobile, seek to convey the sense of swiftness and motion.

Here we see the hallmarks of the 19th century Aesthetic movement: everything is richly textured and no doubt very expensive but ultimately transient. The flamelike beauty of the laburnums echoes Pater’s famous line. The Japanese details reflect the importance of Japonisme, an appreciation for and exoticization of all things Japanese in the second half of the 19th century. We later find out that the cigarettes Lord Henry is smoking are laced with opium.

Lord Henry convinces Dorian to wish for unaging immortality so that he in effect becomes a work of art and leads Dorian down a path that starts with Paterian Aesthetic appreciation but ends in murder. He tells Dorian, “I believe that if one man were to live out his life fully and completely, were to give form to every feeling, expression to every thought, reality to every dream,” then the world would gain “a fresh impulse of joy.” Dorian does just that. He starts innocently enough by collecting jewels, sumptuous fabrics, rare perfumes, and musical instruments, but eventually causes the woman he loves to commit suicide and leads other young men into corruption and disgrace. Meanwhile, he remains young and beautiful while the portrait hidden upstairs grows old and hideous with his crimes. It may seem paradoxical that a proponent of Aestheticism like Oscar Wilde wrote a novel in which the pursuit of beauty leads the protagonist astray. But in an essay titled “The Truth of Masks,” Wilde stated that “in art there is no such thing as a universal truth. A Truth in art is that whose contradictory is also true.” Throughout The Picture of Dorian Gray, Lord Henry speaks in paradoxes, and we are told that “the way of paradoxes is the way of truth.” This contradictoriness is also part of Aestheticism. The preface to the novel is a series of epigrams in which Wilde lays out his Aesthetic philosophy. It ends, “All art is quite useless.” But that doesn’t mean art is useless, as in having no value. Wilde means that art doesn’t have the sort of value Victorian society wanted it to have—it won’t teach anyone morality, patriotism, or any other 19th century virtue. It exists for its own sake. L’art pour l’art.

The preface also tells us, “There is no such thing as a moral or an immoral book. Books are well written, or badly written. That is all.” This attitude is, of course, what got Wilde into trouble. When Bosie’s father, the Marquess of Queensberry, found out that his son was having an affair with the notorious Oscar Wilde, he accused Wilde of homosexuality—a serious charge at that time. Through a complicated series of trials, Wilde was ultimately found guilty of “gross indecency” and sentenced to two years of hard labor in prison. But the trial did not focus on Wilde’s relationship with Bosie—instead, it focused on what he had written in The Picture of Dorian Gray. Parts of the novel were read in the courtroom, and Wilde was asked whether he thought his words might corrupt the young men of England. Wilde defended himself both wittily and valiantly, but to no avail. By the time he was released from prison in 1897, his health had broken down. His wife and sons had changed their names and left England to escape the scandal. He was bankrupt, and Bosie had deserted him. Robert Ross was at his side as he lay dying in Paris. Among his last words was a complaint about the décor: “This wallpaper and I are fighting a duel to the death. Either it goes or I do.”

In 1892 and 1893, the German philosopher Max Nordau published a two-volume treatise called Degeneration in which he railed against what he called the decadent, degenerate art of the late 19th century, identifying movements such as Impressionism and Symbolism as symptoms of a cultural disease that was infecting Europe. Nordau’s book sounds ridiculous to a modern reader—among other things, he claimed that degenerate artists could be identified by unusual physical attributes, like pointed ears and hairy palms. But he was taken seriously at the time.

There was a genuine fear that society was somehow going in the wrong direction, devolving into lower forms. Oscar Wilde was still at the height of his fame and came in for Nordau’s especial ire. What made Wilde such a dangerous figure to Nordau and conservative Victorian society? Probably the same thing that makes him such an important and beloved writer today. Wilde stood up for the freedom of the artist to create, the freedom of the individual to enjoy and experience. He thought society should be kinder, more compassionate. From his cell in Reading Gaol, he wrote about the need for prison reform. He cared about beauty and truth—which may be why he relentlessly skewered Victorian hypocrisy. The society he criticized eventually destroyed him, but we still have his words and a tomb in the form of a winged angel that has to be protected from passionate admirers.

Wilde was famous for his epigrammatic sayings. “We are all in the gutter, but some of us are looking at the stars,” says one of the characters in Lady Windermere’s Fan. Hopefully, the dangerous Mr. Wilde is up there somewhere, looking back down at us, probably with a witty paradox on his lips.