Featured Image:

Mérode Altarpiece (1427–32), from the Workshop of Robert Campin

Illuminated manuscripts—books painstakingly copied on parchment and illustrated by hand before the advent of the printing press—are among the most captivating relics of the medieval period.

Designed as they were to conserve wisdom believed eternal and manifest the endurance of religious faith, it’s no surprise that surviving examples can appear less diminished by time than other kinds of medieval art: the colors more vivid, the care invested in each stroke and line of script still unmistakable. Whereas faded frescoes and fractured sculptures can’t help but suggest glories we will never see, illuminated manuscripts seem to present an intact portal, a more immediate grasp of an era on the other side of modernity.

We are accustomed to books being printed by the thousands, if not millions; we take our ceaseless saturation with media and images for granted. At times the screens can feel inescapable

The ease with which we all can put a frame around any aspect of the visible world and reshare it has a paradoxical way of making things sometimes seem more ephemeral and elusive, as if we were inundated with copies and had lost sensitivity to the originals—or as if originality and uniqueness themselves needed always to be proved rather than assumed. Social media posts can rack up massive numbers of views, but the more viral they become, the less they often seem to matter in the long term.

But illuminated manuscripts present us with tangible evidence of a time when images were scarce and copying was a sacred practice. Each repetition of the prescribed words and of the recognized formulas of Christian iconography condensed their power and reaffirmed their apparent timelessness. Compensating for the limited repertoire of texts and images was the depth of feeling and attachment they made

possible: Novelty was trumped by a more consequential continuity. If mechanical reproduction has undermined art’s aura, casting the entire concept of authenticity into doubt, as historian Walter Benjamin theorized, then illuminated manuscripts remind us that the act of reproduction itself once had an intense aura of its own, one that can still speak to the century-spanning force of concentrated attention.

It would seem like the Cloisters would be an ideal place to encounter illuminated manuscripts. Isolated atop a steep hill in one of Manhattan’s more far-flung neighborhoods, the museum was built from the transported remains of several Romanesque and Gothic abbeys, with its arcades and sparsely furnished chambers expressly designed to evoke the solemnity and contemplativeness of the monastic life. Though its collection of medieval manuscripts is not nearly as robust as that of the Morgan Library in Midtown—a Gilded Age faux temple whose ambience Manuscripts is less contemplation than ostentation—the codexes it has on display in a narrow antechamber of its Treasury room benefit from the subdued, intimate atmosphere. The manuscripts feel appropriately rare here, a select few volumes among the other devotional objects, the jeweled vestments and carved ivories.

Each of the manuscripts exhibited in that particular nook is a Book of Hours, small and often elaborately ornate breviaries produced for the delectation of the wealthy customers who could afford them. These works conflated piety with bibliophilia, allowing devotion to a beautiful book—fingering its vellum, savoring its miniatures and the shimmer of gold leaf, entangling one’s eyes in the acanthus motifs of its richly decorated borders—to appear equal to devotion to God. Books of Hours made private reading into a kind of soul craft, in which intimacy with a text became the means for personal transfiguration. The book implicitly promised to change your life: It provided instruction on how to imitate the monks and fill your day with effectual prayer, premised on keeping the text with you at all times. To read was to pursue holiness (and not, as would later be the case, idleness).

The ubiquity of texts has since changed our relationship to reading. But we can still glimpse something of how books might have been experienced then in the most famous painting at the Cloisters: the Mérode Altarpiece, from the workshop of Robert Campin. Its style and density of detail are influenced by innovations pioneered in illuminated manuscripts, where new techniques of representing space, volume, and landscape had already been worked out. The central panel depicts the Annunciation, where Mary learns from the angel Gabriel that she will give birth to the son of God. Anachronistically, however, this scene is set in what appears to be a realistically rendered Flemish dining room of the 15th century. Mary is shown reading, as would become conventional in Annunciations, but while she holds one book open by her breast, another sits open on the table, looking very much like an illuminated

manuscript, another anachronism. Some interpreters have suggested she is reading from a Book of Hours, which would be full of prayers devoted to herself—an oddly egotistical choice.

All of this makes for a conceptual jumble of space-time as potentially disorienting as the peculiar, almost proto-Cubist perspective offered of the tabletop. But even though isolated details are rendered with striking fidelity, the overall composition is not intended to be documentary. Not only is the panel full of allegorical flourishes; it also invites a fluid interpretation of time and identity, in which Mary is fully present in all times, as an idea any beholder can aspire to inhabit. Mary reads the book and is the book to be read. The book we read is equivalent to the being we should hope to embody, and it is also at once an open book, and a sacred book, and a message direct from heaven. We can imagine that Mary is reading what Gabriel is simultaneously intimating, and the words change her life and everyone’s. The words are for us as well, preserved across time and out of time in the pages we can almost make out, fluttering impossibly open in some spiritual wind in the stillness.

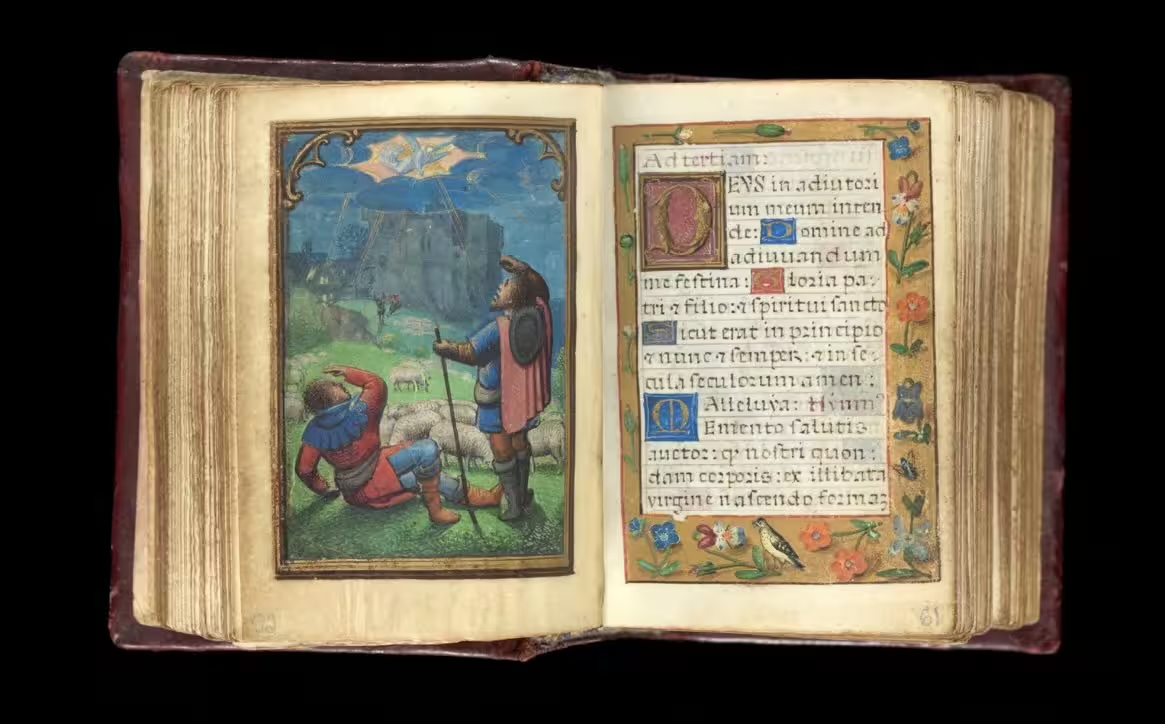

For medieval people, literate or not, books must have been self-evidently potent, whether they were perched high atop a lectern at an altar or nestled snugly into one’s palm. The early 16th century Book of Hours made by Simon Bening on display at the Cloisters is barely bigger than a matchbox, but all the more entrancing because of it. The curators wisely display the tiny book open to a miniature of The Annunciation to the Shepherds, in which angels appear to announce the nearby birth of the messiah to some flabbergasted sheepherders. One has been knocked to the ground in astonishment, while the other shields his eyes with a gloved hand. For Christians, this image depicts the reverberation of a divine miracle, but for the book’s owner it may also have suggested how privileged they were to hold a miracle in their hands. The image evokes how miraculous seeing itself can be, and I felt myself a witness.

By the time that book was made, printed words and images were already beginning to proliferate in Europe, and the sense that any book could be every book, and every book should be holy, transferring a unified body of spiritual knowledge, began to unwind. Scribes became obsolete, and literacy gradually became more widespread. Books continued to change people’s lives but in ways that were much harder for authorities to control. Their aura may have escaped, but their power was set free with it.

Find similar book themed articles in our Book Lovers, our Spring Issue!

Find similar book themed articles in our Book Lovers, our Spring Issue!