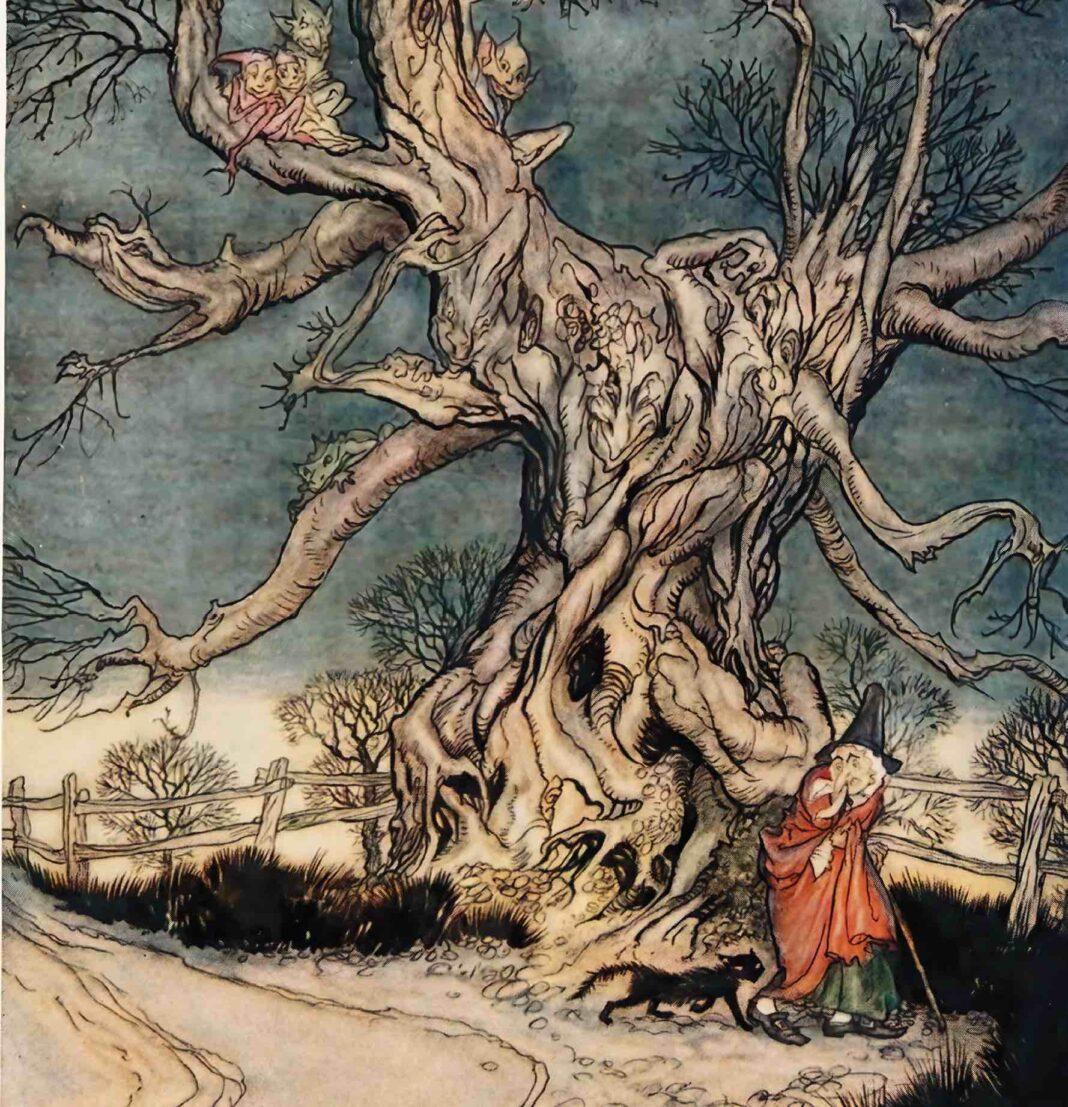

Feature Image: Major Andre’s Tree, from The Legend of Sleepy Hollow (1928), by Arthur Rackham

A confession is required before we begin. Although I spent the earliest years of my life creating colorful syllabi on construction paper describing all the magic lessons I would be teaching my rapt audience of stuffed animals, and although I spent many an hour with my (endlessly patient) calico cat encouraging her to balance on the end of a broomstick, I did not have more than a passing familiarity with the stereotypical image of a witch.

I do have a picture of myself dressed up as a witch. It was taken in my maternal grandparents’ living room, the heavy, straight-out-of-the-seventies goldenrod polyester curtains providing a suitably mystical background, at least in the mind of my seven-year-old self. In the picture I’m wearing a bright yellow Mexican dress, lushly embroidered with flowers and flowing green vines, the kind of dress I had in every color and wore (along with much of the seven-year-old girl population of San Antonio) throughout the summer. You cannot see my feet in the photo, but I’m willing to lay down serious money that I was wearing one of my beloved pairs of jelly sandals. A fake gold chain encircles my head, and my expression is suitably serious and pensive. This, to my mind, was the epitome of a witch. No warts, no crooked backs or pointing fingers, and not a scrap of black cloth in sight. Thirty-five years later, not that much has changed.

The word witch was never a slur to me but nor was it an unqualified compliment. A witch, a bruja, was someone, something, more ambiguous than simply good or bad. A witch was someone who might use their knowledge for good or ill, who might cure … but also curse. Most of all, a witch was someone who had a nuanced, frank, and honest relationship with power. Contrast this to another magical figure in my young life, a curandera. These people were (and are) holy. They dealt in the language of curing and healing only. They worked not for personal gain but for the collective good. Curanderas also had deep relationships with their power, and that power was always in service to the good.

As I grew up, learned more, made magically minded friends, and started taking on clients for myself, I discovered that the divisions were not quite so stark—even and especially in the community—as I had first thought, but they were (and are) still there.

If witch was ambiguous to my young self, magic was not. Magic was everywhere and in everything. Magic was my paternal grandmother lovingly patting her Saint Christopher medallion and talking to him before she revved up her Lincoln … even to drive five miles to the grocery store or movie theater. It was my maternal grandfather watering his plants while standing barefoot on the earth, talking to barn owls—ghost birds, as his culture thought of them—and showing me where the horny toad had made a little den for itself in an old rock pile. Magic was my great aunt who always smelled like gardenias and cheese biscuits and a tiny nip of tequila pressing a wishbone into my tiny hand, teaching me how to pull until the crisp snap was heard while we stood in her fragrant log-cabin kitchen. It was my paternal grandfather telling me old Scottish stories like “Tam Lin” and my maternal grandmother making sure I knew by heart all the best Bible verses, beginning with a full memorization of the twenty-third Psalm. Magic is and was my mother teaching me the names of plants as she shamelessly filches seeds and cuttings from front yards and graveyards alike or picks up dead and broken animals from the middle of the highway to give them a proper burial. It is my father telling me to find work that makes me happy and only after that, makes money. This was the magic I was taught and lived next to day in and day out, and so my brain made the logical connection that the sources of this magic—grandparents, aunties, and parents—were the witches I knew best.

My witches were as far as you could get from the short, twisted, squat, hairy, squawking, cackling, wart-nosed, black-clothed, and finger-pointing varieties with their chicken-footed houses, fang-filled mouths, and endless hunger for children. Or were they?

I first encountered the character of the more stereotypical witch in stories, the fairy tales and myths that were both read and told by heart to me. Later I discovered the image of these types of witches in books and film. While this witch did not feel anything like the witches I was accustomed to, I was fascinated by her … and it was almost always a her … nonetheless. In my growing years I came to understand that the stereotypical witch was not descended from a single image but rather a chimera of images cobbled together through literature and fear, in large part as an effort to explain why magic and power, especially in the hands of women, were not to be trusted.

The witch’s bent and twisted shape and wild cackle bring to mind her shape-shifting abilities and underscore her relationship to animals and the natural world. Yet her penchant for devouring children marks her as unnatural, un-feminine; it runs counter to the idea and ideal of women as bearing and nurturing children. Her appetite, often alluded to in terms of sexual desire, reaffirms the norm that power not be made available to women, or those of a lower class, those who look, speak, smell, or think differently, because they wouldn’t know how to wield it correctly. Even the witch’s pointed finger brings to mind the untactful bluntness of someone who has not been raised to have nice manners, someone raised out of civilization—the rudeness of pointing being one of the first things we teach young children even to this day.

This image of the witch moved me, spoke to me, because I could see her in my witches. She was the witch behind the witches in my life. Not her physical form. My witches wore embroidered blouses and silver jewelry and spectacles and pearls. They carried briefcases that matched their boots and black church purses full of everything you might need during a long, boring service: tissues, Vicks vapor rub, and Sucrets. My witches drove pickup trucks and old brown Chevrolets and had heavy turquoise and silver rings on their earth-loving fingers … which they did, and sometimes still do, point.

So, no, I did not see her form, but I felt her force. I felt her speak through the women and the men in my life who whispered their own spells over my head: Be safe, be brave, find your own way, know your power inside and out, own it, speak with it, write with it … do this for yourself and your babies and for all of us who could not … because we didn’t look right or sound right or speak right or smell right. Do it for us too. And so I do, and so I have, and so I shall. May it be so for all of us.

Briana Saussy is an author, storyteller, teacher, spiritual counselor, and founder of the Sacred Arts Academy, where she teaches magic, divination, ceremony and other sacred arts for everyday life. She is the author of Making Magic: Weaving Together the Everyday and the Extraordinary, and Star Child: Joyful Parenting Through Astrology. See more at brianasaussy.com.