©The Advertising Archives : Alamy Stock Photo

As an act of holiday charity, I beg you to put aside everything America has taught you about the Krampus, especially any thoughts connected to that mirthless horror-comedy that blighted cineplexes last year.

Though the name Krampus is now familiar, it’s also become entangled in countless misconceptions. First there is the linguistic confusion engendered by the film and other American representations, which seem to regard Krampus as the proper name of an individual monster. It is actually a term for a species of folkloric devil that almost always appears in groups. For this reason, I use an article before the word, just as we would say, “the vampire fears garlic,” rather than “Vampire fears garlic.”

A second major error: The notion that the figure is somehow attached to Christmas Eve and Santa Claus. It is on Saint Nicholas Day (December 6) and the evening before that troupes of Krampuses visit homes in Austria and Bavaria accompanied not by a red-and-white-clad Santa but a costumed bishop representing the fourth century Catholic saint. The bishop questions children about their behavior and perhaps quizzes them on their catechism. Those who’ve done well receive a handful of sweets; the naughty are threatened and occasionally may receive token swats from the devils.

That’s the authentic core of the tradition—the interactions with Saint Nicholas as assisted by his Krampuses—but you’ll be hard pressed to find it in any American representations. Even the increasingly well-known phenomenon of the Krampuslauf (Krampus run), now imitated in a dozen or so American cities, is something of an accretion to that core tradition. Before the organization of these formal parades, the presence of Krampuses on city streets was merely the result of roving troupes passing through en route to homes. Today these parades often sideline Nicholas and never feature the formalized evaluation of children’s behavior. Even in Europe, the custom of these visits is slowly being displaced by the phenomenon of the Krampus run.

While muddling or omitting any of these details might be understandable, what really confuses European observers of American Krampusmania is the attitude with which the figure is embraced. Somehow, as if in a fit of teenage infatuation, we have made the Krampus the screen upon which to project youthful fantasies of rebellion. This attitude is rooted in nearly two decades of callow internet meme-think, presenting the Krampus as an “anti-Santa,” or an iconoclastic Christmas killer.

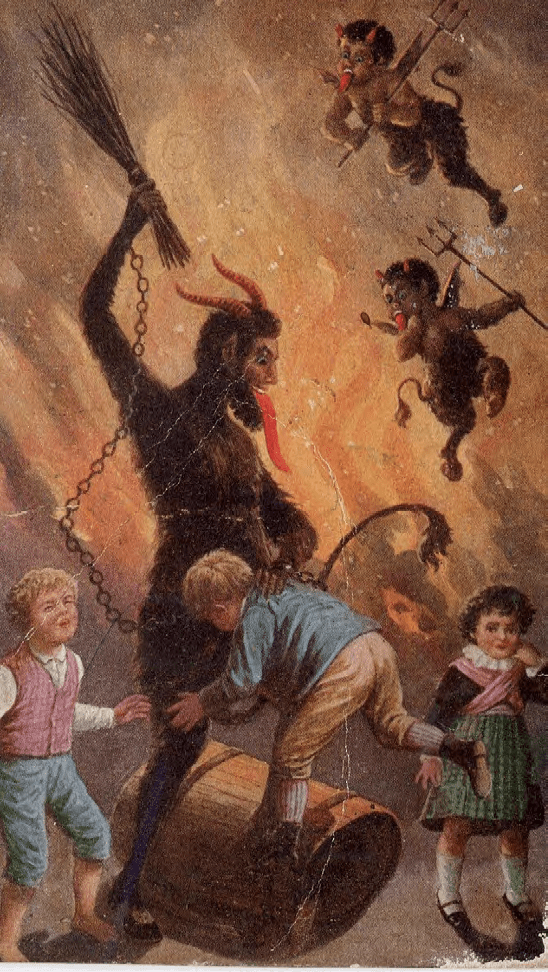

A factor here may be what we Americans saw when we discovered him online via scans of old postcards—the Krampuskarten (Krampus cards) that were all the rage shortly before World War I. What grabbed our attention was the shocking depiction of children fleeing in terror, beaten in countless ways, chained, and even skewered on pitchforks. In days when parents enthusiastically spanked their children and fairy tales went uncensored, images such as these may have elicited a small, grim chuckle, but in 21st century America, they make heads explode. They violate everything we understand about Christmas. If any “true meaning” is today ascribed to the holiday, it’s those fuzzy notions of peace, childlike wonder, innocence, and cozy family life. Reasoning with their gut, American hipsters concluded that they’d found in the Krampus an embodiment of true anti-holiday rebellion, the tonic to the sentimentality of Mom and Dad’s Christmas. If the season must be acknowledged at all—which seems inescapable—the Krampus would be the perfect backhanded response.

Yet, in his proper context, the Krampus embodies a worldview every bit as traditionalist as the Biblical warning about sparing the rod and spoiling the child. He is not the shadowy opposite but equal of Saint Nicholas, much less Nicholas’s enemy or some renegade free agent of holiday mayhem. He is a servant in the Christian world of the saint, and while he may take malevolent glee in administering his cruel punishments, he’s still enslaved by a moral order, always appearing in chains that symbolize his position of servitude.

Pagan-minded readers by now will be wondering if those chains might also represent subjugation of a pagan tradition by the Church. This is a difficult question, because it presupposes a dichotomy that didn’t really exist in the habitat that birthed the creature. The Krampus is not a top-down creation of the church somehow engineered to embody divine retribution. He is a figure of the people, the Volk. He evolved organically from within a family of menacing figures of pagan folklore but was instinctively polished to a more Catholic sheen by the habitually devout populace of the Alps. This form of folk Catholicism that seamlessly mingles earlier heathen belief with Christianity is hard for modern readers to grasp, and the winter holiday they celebrated was likewise terribly remote from the season we celebrate today.

The titular “old dark Christmas” of my book on the Krampus was a holiday edged with a sense of the uncanny, not only in the Krampus’s Alpine homeland but throughout Germany, much of central Europe, and to some extent the U.K. In German-speaking lands, this season began in early December with Advent, or as early as Saint Martin’s Day (November 11). The period between Christmas and Epiphany, the Twelve Nights or “the Twelves” in German, were particularly known as a time when the spirit world impinged dangerously upon our own.

Those nights were chosen by witches for casting spells or congregating on Alpine crags. Various forms of fortune telling were performed at this time, including Bleigiessen (lead pouring), or the reading of shapes formed by molten lead dripped into water. It was the season that transformed men into werewolves, and it brought the Drud to smother and sicken sleepers. From the mountains, one heard the eerie cry of the Seelvogel (soul bird) and Habergeiss, a goat-like specter. The Nebelfrau (mist woman) appeared in marshes, and the forests and moors swarmed with creatures: the Moosweiberl (moss woman), Holzleute (wood folk), and Schratzln (forest goblins). Malevolent beings could even be found in places of industry. The Melhweibl (“flour woman”) dragged millers into the gears of their mills, and the Durandl arose from glass blowers’ furnaces to bedevil artisans or set the glassworks afire. The saints themselves assumed sinister forms during the month of December. On Saint Lucy’s Day, the shrouded Lutz or Lutzelfrau might eviscerate or drown children, and on Saint Thomas’s Day, “Bloody Thomas” stalked the forest with a hammer.

This period between Christmas and Epiphany, or sometimes Saint Thomas’s Day and New Year, was also known as the Rauhnächte, sometimes translated as the “smoke nights,” because it was when incense was burned to drive off malevolent spirits or draw blessings upon homes and barns, if scrupulously censed. Noise was also used to dispel evil spirits. Rhythmic snapping of whips (Aperschnalzen) and the firing of black-powder arms, mortars, or cannons (Böllerschießen) are regional customs originating in this belief.

Particularly common in this regard is the use of bells, and here we have a key to the Krampus’s pagan aspect. Though almost never depicted in those Krampuskarten that define the creature in many American minds, huge bells worn on a heavy belt are (no less than horns and switches) a defining attribute of the creature. While horns clearly link the beast with the Christian devil and switches to his well-defined role as punisher, bells are hard to explain without reference to pagan belief. If the Krampus is merely a way the folk represented the Christian devil or his demon, why would bells said to dispel evil spirits be worn?

A clue comes from an older, ambivalent figure from Austro-Bavarian folklore—the Percht. Also impersonated in costumed folk customs of the Twelve Nights, and particularly Epiphany Eve, the Percht is likewise outfitted with bells, and his appearance is usually all but identical to the Krampus. Unescorted by a Saint Nicholas, these figures once traveled from home to home bringing (despite their frightful appearance) good luck to those who would receive them. Over the course of time, rowdy nocturnal visits by these troupes came to be viewed as troublesome, and the pagan Percht, soon to be called Krampus, was tamed by the civilizing influence of a Saint Nicholas accompanying the troupe as a sort of moralizing chaperone.

All this may seem a tidy explanation, but there is also a species of Percht completely lacking resemblance to the Krampus. These are called the Schönperchten (beautiful Perchten) as opposed to the Krampus-like breed known as a Schiachperchten (ugly Perchten). In Austria’s Gastein Valley, on Epiphany and New Year’s Day, the “beautiful” species can be seen on parade, represented by figures such as the Kappenträger (cap wearers), whose headwear consist of towering structures elaborately adorned with artificial flowers, mirrors, old jewelry, dolls, ornaments, and even taxidermy. Likewise, in the nearby Pinzgau region, we find Schönperchten, known locally as Tresterer (stampers). Since at least 1841, they have performed a peculiar dance while outfitted in ornate brocade suits and caps with cascading ribbons. Their dance, like one performed by the Kappenträger, is said to bring good luck, health, wealth, and robust crops.

The Schönpercht, however, is a relatively recent invention dating only to the very end of the 19th century. Latest scholarship suggests that just as Saint Nicholas was inserted into rowdy Percht outings as a pacifying element, the creation of the Schönpercht was a way to civilize or supplant the mischievous forays of the poorer classes carousing by night in devilish costumes of rags and old furs.

While these two distinct species of Perchten may be a recent invention, the idea reflects a genuinely ancient notion of ambivalence attached to the word Percht, which first appeared

in 13th century texts and was used originally to describe a female entity surprisingly similar to the Krampus. She is Frau Perchta, sometimes known as Frau Percht, Bercht, Berchta, Pehrta, Berthe, and other variations, as is common in dialects of German. Her appearance was said to be frightful, with a sooty face or garments, wild hair, and a long nose, sometimes said to be of iron. Rather than on Saint Nicholas Eve, she visited homes on the eve of Epiphany, a day called in Old High German giberahta—meaning “shining forth” or “manifestation,” (i.e., epiphany). It is from that word that the name Bertha is derived. Her purpose was to ascertain whether the women or servants of the household had completed their spinning and other chores by this date. If they had been remiss, Perchta employed her knife or sickle to slash open the miscreant’s belly, gutting her victim, stuffing the cavity with snow, rocks, straw, or other debris, and then sewing it all up with an iron needle.

While slashing bellies may sound rather more straightforwardly malevolent than ambivalent, Perchta was also said to convey blessings to a home if certain acts of homage were performed. If we return to the previously mentioned 13th century text—a tract entitled The Mirror of Conscience—we find an unnamed cleric condemning those “who, on the night of Epiphany, leave food and drink upon their table so that all shall smile upon them over the coming year and good luck will grace them in all things … Therefore also sinning are they who offer food to Percht.”

This practice of setting a Perchtentisch (a table for the Perchten or Frau Percht), like the censing of homes during the Rauhnächte, is documented up into the early 20th century and is likely still carried on here and there, albeit more out of traditionalism than superstition.

Ecclesiastic writings from the Middle Ages onward lump Perchta together with Diana, Holda, Herodias, and other figures associated with witchcraft, ascribing a devilish quality to her and her followers. In the process, the name Percht seems to have come to represent a more generalized sort of bogeyman or malevolent spirit associated with those days near Epiphany. A few texts from the late 19th and early 20th century mention a costumed individual identified as a female Frau Perchta or the Percht visiting homes to threaten negligent spinners, as well as naughty children in general, with the sort of discipline earlier described. But more common to the season were visits by men or male youths impersonating multiplicities of Perchten. While evaluations of children’s behavior would not be part of these customs, “good behavior” in the form of tributes of food, money, or drink would be expected from the householders. In return, residents would receive a blessing, one sometimes formalized with the performance of a particular song or dance (from which dances like those of the Tresterer, for instance, might be presumed to originate).

Another essential (and benevolent) role of Perchta was her protection of children who die unbaptized. As leader of a host of infant ghosts (the Heimchen), she is connected with the other myths of spectral processions common to the Twelve Nights. The dead were said to wander in Bavaria, Austria, and Switzerland as the Nachtvolk (night people), Totenvolk (death people), or Totenschar (death throng). Similar tales were also found further north in Germany, where the spirits are more commonly identified with the general mythology of the Wild Hunt, or Furious Army (often so named irrespective of whether the assembled ghosts are those of departed soldiers or hunters).

Because of the pagan nature of these beliefs, such myths of the wandering dead came to be described in increasingly frightful and demonic terms by the church, and the departed spirits became warlike specters or were given new infernal purpose as hunters of souls. But in the folk tales of the people, the dead were also enthusiastically welcomed with rituals like the laying of the Perchtentisch, one viewed as a happily reciprocal act of communion. Foods left overnight for the Perchten, which the materialist would see as untouched, were said to have been magically consumed, then magically refilled. The replenishing was regarded as affirmation of the ongoing and nurturing role of the dead, as they embody the boundlessness of the next world and the source of all plenty.

Returning finally to the Krampus, it is interesting to note that some scholars derive the creature’s name from the Bavarian word Krampn, used to describe something dried out, shriveled—or dead. Having explored connections between the dead and the Percht or Frau Perchta, it shouldn’t surprise us if these connections held also with the Krampus. Perhaps in days prior to his servitude to Saint Nicholas, before he was transformed into a devil, he was simply a wandering ghost—dreadful as any figure from the other side might be but perhaps also at times benevolent. Could the modern figure show traces of this history? In the milieu of folk Catholicism, where the dichotomies of theology dissolve and figures like the terrible Perchta can also tenderly guard the souls of lost children, could not blessings also come from a devil—at least one wearing bells?