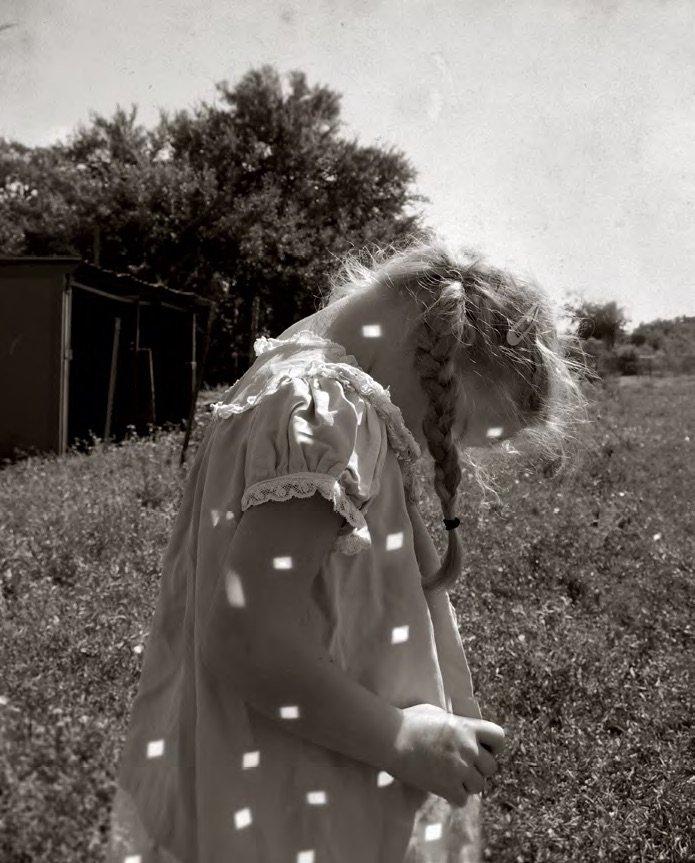

Feature image by: Darla Teagarden

I was raised by a Southern tribe of women who believed in Jesus and could tell the future. The Jesus part was easy. It was easy as heat lighting on a summer night. They were Southern and Jesus ran through their blood like pinesap through the trees. You would think that the nature of God would draw more questions for the telling. More back chilling, spine-tingling mystery, but this was not the case. This was the black and white of it. The cut and dried. The Family Bible on the table. Prayers called out over food and footsteps. Sunday, go to meeting. Jesus was no mystery. Jesus was real. This future shrouded in foreboding and signs of all kinds, now that was a mystery.

The men in the family knew no future other than the day at hand. They were tough and tumble guys. They fished, they hunted, they worked, they drank, and they told lies and alibis. The telling of the things to come was not a part of them. Hard work was a part of them. Alcohol was a part of them. They were made up of three parts survival and one part mischief, and so while the men stayed grounded to the earth, to mills and cotton fields, the women were the mistresses of all manner of things. They pulled their shifts, picked cotton, worked peanut mills and water wells—but they were also the mistresses of the other things that were a part of life.

They cooked the food and rocked the babies. They tended to the things that fell into their charge and keeping. Blessings and dinner on the ground. Signs and wonders. Dreams and foretellings of different kinds. And the women drank this portion of their cup without complaint. Carried the burden of all of it and the men let them carry it on, following from a respectful distance, shuffling on the edge of mystery.

These mothers of mine, for they were all mothers, could tell things by the weather. By the way wild animals appeared and disappeared. They could call the sex of an unborn child, tell it by the way a woman walked, know if a boy-child or a girl-child was coming. They could find a missing husband cold turkey in the middle of the night three cities away in a stranger’s bed, and in some cases, they could tell fortunes. For them the veil between time and distance and other worlds was thin, more gossamer than brick.

Like the morning that my Grandmother rose from a troubled sleep and announced at the buttering of the biscuits, “Last night I had a dream of muddy water.” She paused, took a sip of her coffee from a plain, white cup, and looked up.

“Go on,” my mother told her. So she did. “I was standing on a bridge looking for something, looking up and down that creek. The wind was dead and silent, completely absent. The water was full of mud and sorrow. Barely moving.” She looked at my aunts seated around the table, her eyes passing over my head that barely cleared the table’s edge as I sat in my mother’s lap. “I never found what I was looking for.”

Then the circle of aunts shook their heads, went to tsk-ing with their tongues, and picking up a thread of worry. What would come next? A sick child? Dead animals? A husband hurt or worse? And the worry would continue until, sure enough, the dream would fulfill itself. Bad times, once on a distant horizon, would land nearby.

On frequent nights, too small for much of anything but being rocked, I stayed there in that old house and slept alongside my grandmother. A tiny thing lying in that big iron bed, the sound of those old fans with blades that could chop a finger off spun everywhere, rotating, stirring the hot air. Me, so small with eyes open, still awake, I’d look out the window across the dark field and into the woods. As I lay there, not sleeping, the sole survivor of the day, still wakeful, still watching, I’d see thunderstorms move across that field towards us. Watch as they drew nearer until thunder shook the house. Until lightning was upon us. Until the very air hissed, cracked, and rolled. Until I thought we were going to die. Yet, my grandmother slept on, breathing evenly in and out, exhaling sights unseen over me until finally I drifted off into a hot, Southern, sleep of my own.