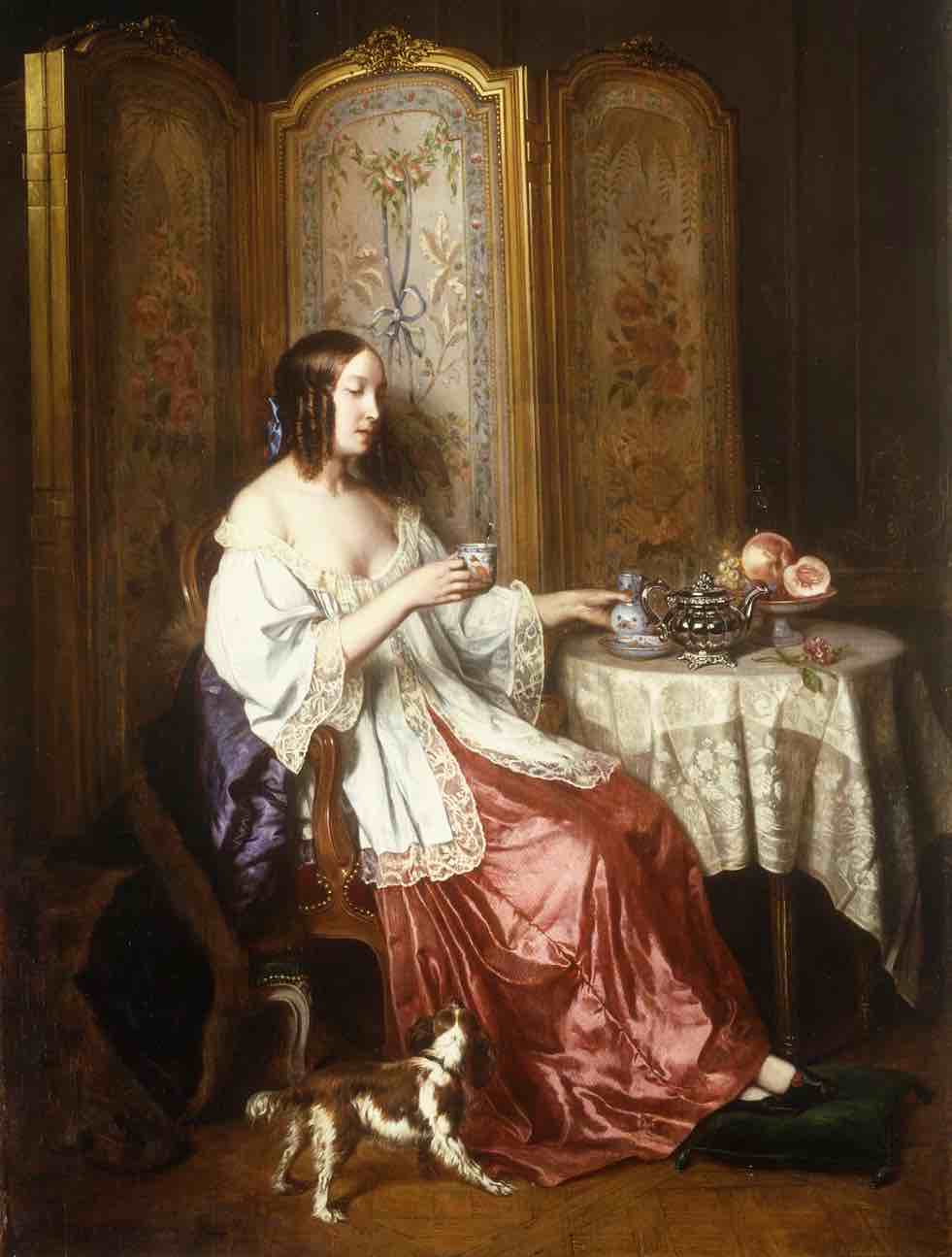

A Cup of Chocolate (1844), by Charles Beranger

© Christie’s Images / Bridgeman Images

At nine o’clock the next morning his servant came in with a cup of chocolate on a tray, and opened the shutters. Dorian was sleeping quite peacefully, lying on his right side, with one hand underneath his cheek. He looked like a boy who had been tired out with play, or study.

—The Picture of Dorian Gray, by Oscar Wilde

The decadence movement, coincidentally or not, coincided with “the great chocolate boom,” when chocolate consumption, production, and import rose dramatically in the West. Visiting the American frontier as part of his lecture tour in 1882, Wilde inspired his hotel manager in Iowa to serve him his hot chocolate in a cup as thin as the “tender petal of a white rose.”

But after the great boom made chocolate widely available, people became far less delicate about their candy consumption. The frenzy led to a 1920 proposal put to the English Parliament that would prohibit the sale of candy in theaters at night, in a “sugar-saving” move. A drama critic in London protested that “chocolate is the foundation of our drama.” In an article in the Brooklyn Daily Eagle on the subject, an American journalist wrote dismissively of the excessive candy eating of London theatergoers: “Men alone, women alone, children, whiskered aged men, women with teeth, and without ’em, chew, and lick, and gulp in a fashion unapproached in America. Once in the blackness of the theater the grim, reserved Britisher throws aside his restraint and abandons himself to an orgy of candy gluttony.”

That same year, an Australian critic wrote in The Age that “perhaps the chief purpose of the modern theatre is to be an eating house where chocolate is served in the stalls and ice cream in the galleries … It is not outside the bounds of possibility that the control of the theaters will very soon pass out of the hands of those who still make some pretense to provide dramatic entertainment and pass into the hands of those who provide lollipops.”

As usual, Paris was decades ahead in such decadence. In Bizarre: An Original Literary Gazette (1855), Carl Benson wrote of the Folies-Nouvelles of Paris, a “pantomime theater” that had become a place where “people eat sugar candy.” He goes on to write that “said candy (sucre d’orge a l’absinthe) is atrociously bad stuff, by the way, tasting like tansy tea coagulated, but it is the chic to eat, or rather suck it.”

Decadence aside, apostles of temperance pushed chocolate as a salubrious substitution for liquor. But rest assured, delinquents grew quickly deft at corrupting candy, creating an eternal friction between the childlike nature of sweets and the naughty potential for moral and dental decay.

“Give the children plenty of pure sugar—and they will not have need of cod-liver oil.” This was part of a treatise for the moral foundation of candy making, as represented by the industry itself, in the article “How to Sell Confectionary” by a representative of the National Candy Company in 1910. He also celebrated the role of candy in the military: “The United States government buys pure candy by the tons and ships it to the Philippines to be sold at cost to the soldiers. All men crave it in the tropics, and the more they get of it the less whisky they want.”

And the industry provided in other humanitarian ways too, he insisted. “It may be a jocose estimate,” the candy man said, “but it is said that there are fifty thousand widows in England who get a living by conducting small confectionary stores.”

It’s perhaps this line of thought that led to Candy Medication, a guide published in 1915 by Bernard Fantus, M.D., who claimed to have experimented with cod-liver-oil chocolate cream. But such experiments led to more successful marriages of candy and pills, and he offered among his recipes “sweet tablets of opium.” In his introduction, Fantus explained that “it is the author’s hope that this booklet may be instrumental in robbing childhood of one of its terrors, namely, nasty medicine; that it may lessen the difficulties experienced by nurse and mother in giving medicament to the sick child; and help to make the doctor more popular with the little ones.”

Meanwhile, other doctors were offering dire warnings about such candy-coated contentment. In his Second Book on Physiology and Hygiene (1894), J.H. Kellogg warned of sweets spiked with booze: “Children have been found in a state of partial intoxication as the result of eating freely of such candies.”

Candy injected with whiskey or brandy came to be called “wink drops,” according to an article in a Kentucky newspaper in 1896. In what may have been a warning or a celebration, the paper noted that “the very latest phase of social wickedness is the bonbon with the little ‘jag’ concealed beneath its sugary exterior.”

So the temperance movement was quick to revise its advice. Under the subheading “Ways to Drunkenness,” New Catholic World (1899) depicted the drunken woman as someone who “as a matinee girl … fills her bonbonniere with the brandy-drops and absinthe candies sold so freely in the up-to-date candy-shops. Or it may be that she takes paregoric or peppermint frequently when she doesn’t feel well, and Jamaica ginger at the slightest excuse.”

It stands to reason, then, that the candy industry has had a long history of peddling adult indulgences in sweet facsimiles, from candy cigarettes to candy lipstick. (“Put it on, eat it off,” the package encouraged.)

The mayor of Elizabeth, New Jersey, in 1968, called for a ban on the “Hippy Sippy” novelty candy, which critics said too closely resembled a drug addict’s hypodermic needle. The narcotics commission and local parents complained that “the novelty is as unsuitable for children’s play as toy rat poison.” To make matters worse (or, perhaps, better for the candy dealer), Hippy Sippy was sold with lapel buttons promoting the candy with lines like “I’ll try anything” and “We sell happiness.”

Sippy Powered Candy (no relation to Hippy Sippy, as far as I know) and Mini-Cola Candy, both sold with straws, sent Clair-Mel City, Florida, into a tizzy in 1989, according to the Tampa Tribune. The stuff was as snow white and powdery as nose candy, and the kids at school were snorting it, cocaine-style. “I plan to take the candy off the shelves because kids seven years old can’t handle this,” a convenience store manager said. He hadn’t done it yet, though, because of its popularity.

But candy makers have gotten in trouble even when their tainted candy hasn’t intoxicated. In France in 1974, Michel Ricoud sold candy that he promoted as aphrodisiacal, but a court testimony found the sweets contained no such potential for arousal. “I offered hope,” he pleaded with the court. “I brought illusions, I created a psychological effect which made my clients happy.”