Article from Issue #27 Subscribe | Single Issue

PHOTOGRAPHY BY VIONA IELEGEMS

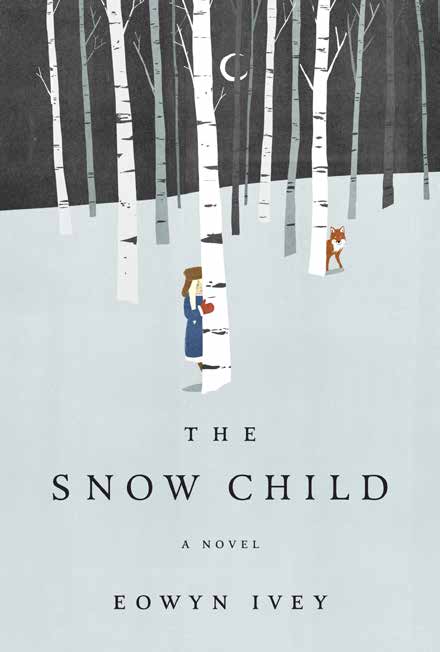

Ewyn Ivey’s award-winning 2012 debut novel The Snow Child tells the story of a husband and wife who move to Alaska as a new start and a welcome distraction after suffering a personal grief. Life is harder than they expected, and the winters brutal. One night, in a rare lighthearted moment, they make a girl from snow, shaping her from the season’s first falling flakes. The next morning, a blond-haired girl appears in the trees. Inspired by the Russian fairy tale of the Snegurochka or snow girl, The Snow Child is both poetic and immersive, perfectly calling to mind the completely unique and relatively untouched wildness of the Alaskan wilderness.

Faerie Magazine: Can you tell us about the Snegurochka fairy tale that appears in The Snow Child? Where did you come across the tale? What was its appeal for you?

Faerie Magazine: Can you tell us about the Snegurochka fairy tale that appears in The Snow Child? Where did you come across the tale? What was its appeal for you?

Eowyn Ivey: I found a children’s version of the fairy tale while I was working at Fireside Books here in Alaska, and it was one of those lightning bolt moments. I read the book standing right there at the shelves, and I thought, “Wow, this is it.” I wasn’t looking for an idea—in fact, I was in the middle of writing a completely different novel. But there was something about the story, this mix of the beauty and danger of the northern wilderness, the couple’s intense longing for a child, that just set me on fire. I ended up abandoning that first novel and diving into The Snow Child.

FM: Did this tale spark the whole novel for you?

EI: In many ways I was coming at The Snow Child from the opposite direction than other fiction I had written. Instead of having the characters in mind and then following their paths, with The Snow Child I had a basic plot structure almost instantly, but I had to discover who these people were, how they had come to Alaska and what this child would mean in their lives. At the same time, along the way, I felt the freedom to at any time leave the traditional plot line if I wanted. The fairy tale provided this wonderful framework around which I could work.

FM: Have you always loved fairy tales (if you do!)?

EI: To be honest, I have never been enamored with fairy tales. As a child, I often found them flat. The characters are simple outlines and there is this sense of “this happened, and then this, and then this,” in a plodding way. I read a lot of fairy tales, but I always left slightly disappointed, like I was hoping for more. Yet something about the Snegurochka fairy tale spoke to me. Maybe that is one of the interesting aspects of fairy tales—because they are plain in their structure yet speak to so many universal experiences, we are then able to fill in our own details.

FM: Why do you think fairy tales continue to be so popular and have such an important place in our culture?

EI: This is fascinating to me. I didn’t realize as I was writing The Snow Child that I was riding a tide of interest in fairy tales. I was just following my own inspiration as a writer. But there is a clear resurgence of books and movies and television shows inspired by fairy tales, and this is the question I keep asking myself—why now? What is it about our culture that at this moment we are so drawn to these stories? I haven’t come up with an answer, but I would love to hear other people’s thoughts about this.

FM: Do you have any favorite Alaska fairy tales, myths and/or legends?

EI: It’s funny because right after I say I’m not particularly drawn to fairy tales, now I’m going to tell you that my current novel is largely inspired by Alaskan fairy tales. In Shadows on the Wolverine, I am working with Alaska Native myths and the legends told by gold miners and other adventurers. One of the elements of Alaska indigenous stories I love is the fact that the line between wild animals and humans is permeable. Bears, otters, wolves all at different times take human form and interact with the people, and they are sometimes threatening, sometimes helpful. There are also recurring Alaska stories, among both explorers and Natives, about lake monsters and mountain spirits that give me goose bumps.

FM: How does being an Alaska native inform your writing?

EI: Alaska is where I start as a writer. Alaska is a complicated place, wrapped up in a lot of romantic notions and stereotypes. At the same time, even having grown up here, it remains mysterious to me. Somehow it manages to be beautiful, terrifying, lonely, tranquil, and overwhelming. It can both isolate people and bring them together. Maybe this is true of all places, but for now I have more than enough material to work with right here.

FM: Do you believe there’s anything magical inherent in Alaskan life, or the Alaskan landscape? Does incorporating myth and fairy tale into your writing somehow better capture the Alaska you love?

EI: I suspect that no matter where I grew up or made my home, I would have been drawn to the myths of a place. Before I came across the Snegurochka fairy tale, I was writing modern realism set in Alaska, and to be honest I was bored with it. As a writer, I needed to give myself permission to bring just a little bit of mystery and magic to the everyday. The fantastical elements are somewhat self-serving— they make the process so much more fun and thrilling for me. And at the end of the day, that excitement I feel as a writer is my primary motivation.

FM: Your book in part deals with the solitude and darkness of an Alaskan winter. Have the long winters had an effect on storytelling traditions there, do you think? And/or on your own love of stories and fantastic tales?

EI: I have always been an avid reader, and I do find I read more during the long, dark winters. So do a lot of people up here. I have to say, I think per capita we have an incredible concentration of creative and artistic people in Alaska, and I sometimes wonder if the extremes of the landscape help foster that.

FM: How have you responded to the reaction that The Snow Child’s received (and your Pulitzer nomination)? Did you ever anticipate such a reaction when you were writing the book?

EI: It has been astonishing. Going into the process as a bookseller, I felt I had a fairly realistic grasp on how difficult it can be to get published at all, much less have a book get any attention among the many being released each year. Thanks to The Snow Child, I can now write full time, and my family and I have gotten to travel more than we ever would have been able to otherwise. But on a day-to-day basis, my life here in Alaska is very much the same as it has always been. And I’m grateful for that.

FM: What are you working on now?

EI: I’m almost done with a draft of my next novel, Shadows on the Wolverine. Like The Snow Child, it takes place in Alaska. It is even set on the same imaginary river I created in The Snow Child—the Wolverine River. But I am going back in time to an 1885 military expedition into the heart of Alaska. As the men venture farther into the country, they begin to encounter fantastical creatures and spirits. I am writing the story entirely through the diaries of the colonel leading the expedition, letters from his wife Sophie, newspaper articles, reports, and other documents.

FM: Do you have any advice for other writers working with fairy tale and myth?

EI: I always hesitate to offer up guidance, because there are so many different ways and reasons to come to writing. Personally, I do best when I write what I am craving as a reader.

But I won’t hesitate to give this advice—read, read, read. Writing can feel like a solitary art, but in fact we are working within a wonderful, rich tradition, and to be active participants, I think we really need to engage with it.