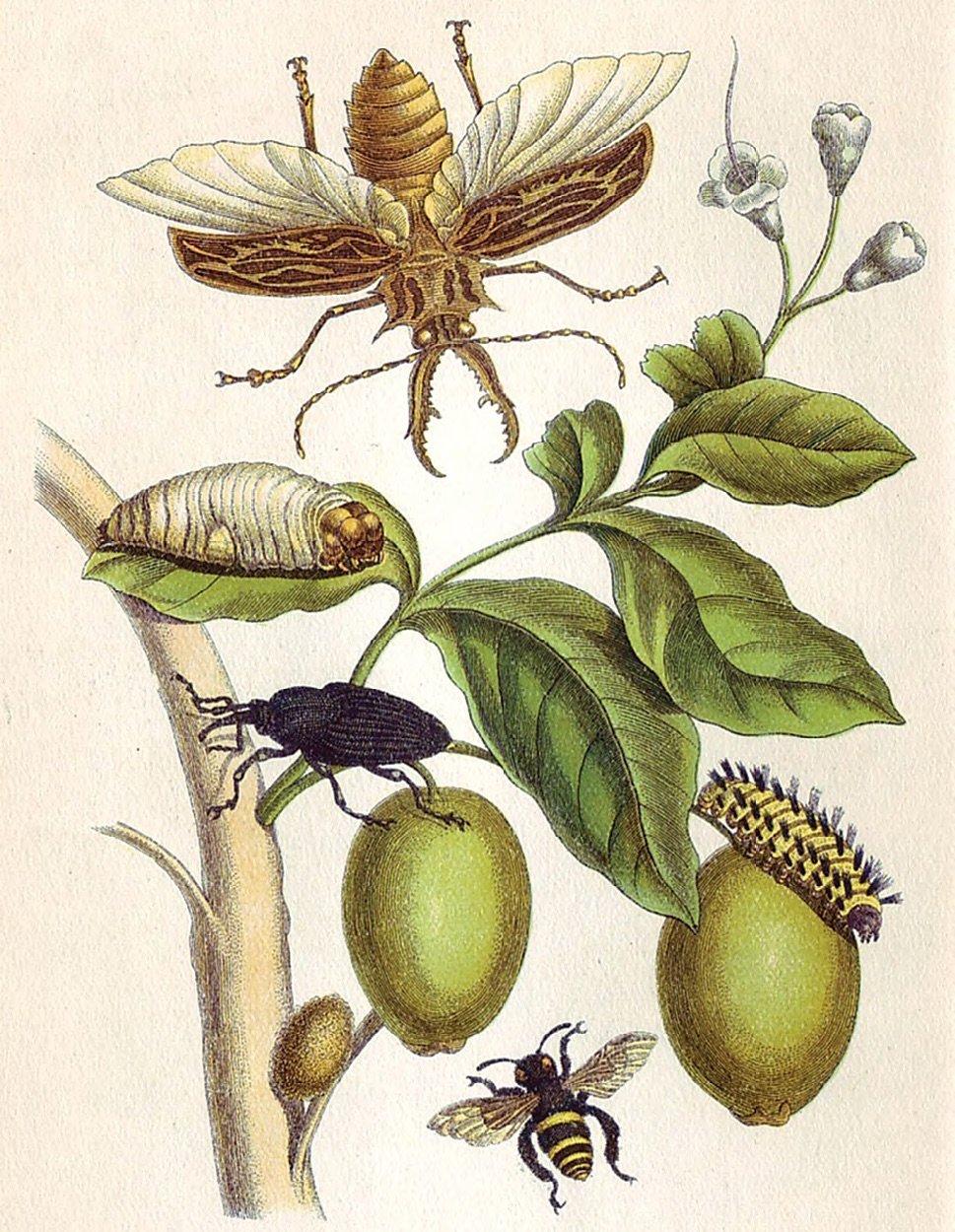

Illuminated copper engraving, 1705, by Maria Sibylla Merian. Wikimedia Commons.

The traveling bug lover, in the earliest days of insect study, brought back from foreign trips magical tales of sailors becoming drunk and dizzy from sucking on honeycombs built by intoxicated bees, of beetles that sprayed a rose perfume, of villagers who strung together glowworms to light their way in the dark.

Poetry and fantasy were key to entomologists’ research, a whimsy that sometimes tested their authority. “Madame Merian had a poetic fancy,” declared a Mr. Davis, with a condescending huff, at a meeting of the Entomological Club in 1836. He’s speaking of Maria Sibylla Merian, the pioneering entomologist and scientific artist. She did groundbreaking research during her travels in the early 18th century, gathering insights into metamorphosis and other fabulist tales. And though her work is still admired and consulted today and her art still exhibited, Mr. Davis found it all too fantastical. In his lecture, he speaks of her “gross misstatements” and stories more fabulous “than which the history of gnomes and fairies cannot boast.”

He also refers to the legend that Madame Merian illustrated a luminescent bug in the night by using the light of its glow as a lamp, though these were not her own claims at all: They were tall tales attributed to her, inspired by her fame for discovery. Nonetheless, he stirred up a heated debate among his club members, demanding that they make changes to their motto and logo, which reference Madame Merian’s research. He proposed that they acknowledge the inaccuracy and that “the representation of Fulgora Candelaria, which appears on the wrapper of the Entomological Magazine, be forthwith deprived of the radii intended to indicate luminosity, and that the motto, signifying ‘allow me to illuminate the world,’ be henceforth omitted.”

He was so determined to dim her glow, he was dimming the glow of the entire club. They were right, though; she and other entomologists had noticed that the bug glows in the dark, but later scientists would determine it was likely a bacteria that gave it its shimmer. But other of her “fancies” cited by Mr. Davis have since been proven sound, such as the leaping tarantula that was only just recently named after her.

But Madame Merian’s humiliation wouldn’t end with Mr. Davis. Her listing in the book Women in the Fine Arts (1904) concludes with: “This extraordinary woman, whose studies and writings added so much to the knowledge of her time, was neither beautiful nor graceful. Her portraits present a woman with hard and heavy features, her hair in short curls surmounted by a stiff and curious head-dress, made of folds of some black stuff.”

Despite this criticism of her folds of black stuff, Madame Merian, as with many entomologists and fashion designers, appreciated the links between insects and style. The 19th century entomologists William Kirby and William Spence wrote of “the beaus of Italy” catching fireflies “to adorn the heads of the ladies with these artificial diamonds by sticking them into their hair.” They wrote also of the Elater noctilucus, a glowing beetle, worn in St. Domingo, one on each big toe.

Kirby and Spence cite the story of a maid who worked for the biologist Jan Swammerdam and discovered a number of wood lice in his garden; the bugs roll up into a little ball when alarmed. Mistaking them for beads, “she employed herself in stringing them on a thread; when, to her great surprise, the poor animals beginning to move and struggle for their liberty, crying out and running away in the utmost alarm, she threw down her prize.”

This impulse may somewhat speak to inclinations by designers such as Elsa Schiaparelli, who created a necklace designed to make it seem as though your sweater were crawling with bugs. More recently, Jennifer Herwitt has designed jewelry such as a choker of linked ants in yellow gold and a diamond butterfly belly ring as part of her “Collection of Living Jewels.” The fashion designer Nicholas Godley has harnessed the cannibalistic golden orb spiders of Madagascar, which spin a strong, silken web, to create fabric.

And scientists have written of insects that demonstrate a fashion sense that dovetails with their sense of survival.

“If you place a number of large ant-flies in a box, the wings of many of them will, after some time, gradually fall off like autumnal leaves,” writes William Gould in 1747. “These [wings] are, to other insects, their highest decorations, and the want of them lessens their beauty, and shortens their life. On the reverse, a large ant-fly gains by the loss, and is afterwards promoted to a throne, and drops these external ornaments as emblems of too much levity for a sovereign.”

Kirby and Spence tell of a lace-winged fly that intimidates by wearing the pelts of its victims, a thick coat “composed of the skins, limbs, and down” of aphids. But they’re just as happy to dress in something pretty; the scientists placed a fly in a glass bottle with a silk cocoon and slips of paper, and the bug put those on too.

James Rennie, the Scottish naturalist, seemed particularly appreciative of the whims and follies of insects, and even attributes the damage they do to a fashion sense they share with humans: “The moth that eats into our clothes has something to plead for our pity, for he came, like us, naked into the world, and he has destroyed our garments, not in malice or wantonness, but that he may clothe himself with the same wool which we have stripped from the sheep.”