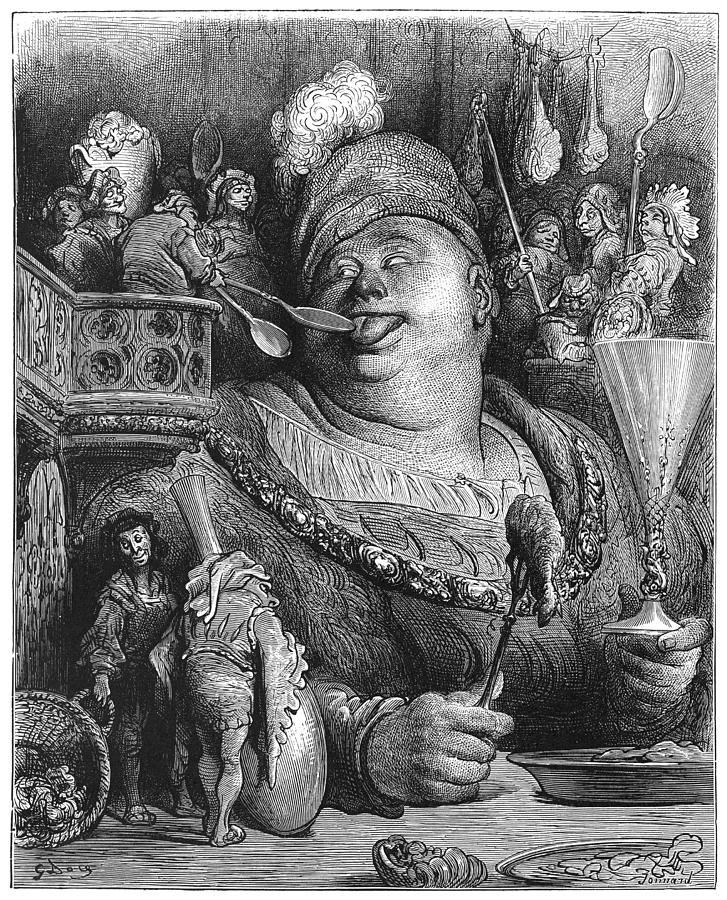

Illustration by Gustave Dore. Stefano Bianchetti / Bridgeman Images.

A pie as big as a table, stuffed wit h everything edible known at the time. Sausages raining down for Fat Tuesday. A memorable salad in which pilgrims have become lost among the lettuce leaves …

This is daily fare for the giants of Gargantua and Pantagruel, the five-volume novel by medieval monk turned doctor turned literary darling François Rabelais. And the book is dedicated to you, “most illustrious drinkers”—whatever your beverage of choice might be—not to some namby-pamby heavenly Muse or heavy-bottomed king. So it’s time to raise your cup and revel in the sheer fact that you can swallow—and read—and if you can do this, all the abundance in the world is yours.

It may not be too much of a surprise that in 1532, when the first of the five books exploded into a Catholic-dominated France, the literary community sat up and cheered. They created the words gargantuan, meaning huge, and Rabelaisian—marked by earthy humor and a celebration of bodily functions. All of the bodily functions.

Rabelais himself was born around 1494 in Chinon, France, where you can visit a house and wine cellar that may or may not be the one where he was born. As a monk, he studied law, languages, philosophy, and science before leaving the abbey for medicine. He established himself by writing pamphlets that were as funny as they were critical of authority, but his writing really took off only when he married fancy French epic poems about genteel ladies and brave knights to popular folktales and jokes about giants and their appetites.

Don’t worry too much about the pilgrims in the salad. Gargantua vomits them out again, which leads to the other end of digestive revelry. Emptying the body is almost as much fun as filling it, and Rabelais enjoys reminding us that what goes in must also come out in some form. So when a giant gets out of bed in the morning, he relieves his bowels, ladder, lungs, nose, and so on—a painstaking catalog—all the better to take in food and drink.

And as to you, dear reader: To enjoy this book fully, you have to eat and drink while you read. That’s the way to ingest the author’s message, and it’s hard to say whether there’s more pleasure to be had from stimulating the mind or the tongue. Rabelais claims to have dictated his chronicles for a giddy lark while he was in his cups too. He must have been there for quite a long time; the five volumes are a feast of 700 pages.

It might seem surprising that the characters’ chief hunger is for food and books; sex is a separate appetite, and it isn’t tied to what’s on the table (though the sheer number of sausages that appear in these pages might give one pause). Panurge, a fast-talking sidekick slightly under the devil’s influence, agonizes over taking a wife, lest she betray him. It seems that food and drink are the one love you can rely on … but in an era when so much of the meat available was rotten or of questionable origin, eating the way these characters do was as great an act of trust as any marriage.

When the first book appeared, the printing press was less than a hundred years old and the novel as we know it hadn’t been invented. Rabelais took a big step into modern literature. So perhaps the greatest abundance of gifts is in the book itself, as the Prologue takes pains to remind us: It’s like a box with frivolous decorations in which the reader will find “a heavenly and inestimable medicine”—a good part of which is the bawdy humor.

Rabelais wants us to laugh, because laughing lifts up the spirit and brings us to a new level of being. It shows you that you’re human; it gives you strength when there isn’t much on the table. In the best of times, it turns the world upside-down and remakes it anew.

And yet, he also insists, it’s a mistake to dig too deep for meanings that lie beyond pleasure—a disclaimer Rabelais might have added to fend off the Church and French Parliament, both of which tried to censor his work.

Who doesn’t eat up a paradox?

The source and authorship of the last volume are controversial; it appeared nine years after Rabelais died and may or may not have been based on his notes. But it introduces us to the oracular Goddess Bottle of Lantern Land, who delivers the ultimate message in a single word: “Drink.”

So the journey continues.

Under the heading of last words, Rabelais’s might be his most famous. When he died in 1553 (of causes unknown), he declared, “Je m’en vais chercher un grand Peut-Être”—“I go to seek a Great Perhaps.”

It’s okay to laugh. More than okay. By laughing, eating, drinking, and (ahem) digesting, we celebrate—and sustain—life. We can make great art. We can bring the world from darkness into that Great Perhaps.

Susann Cokal is the author of four novels, three of which take place in an enchanted Scandinavia. They include the award-winning Kingdom of Little Wounds and her latest, Mermaid Moon. Visit her at susanncokal.net.