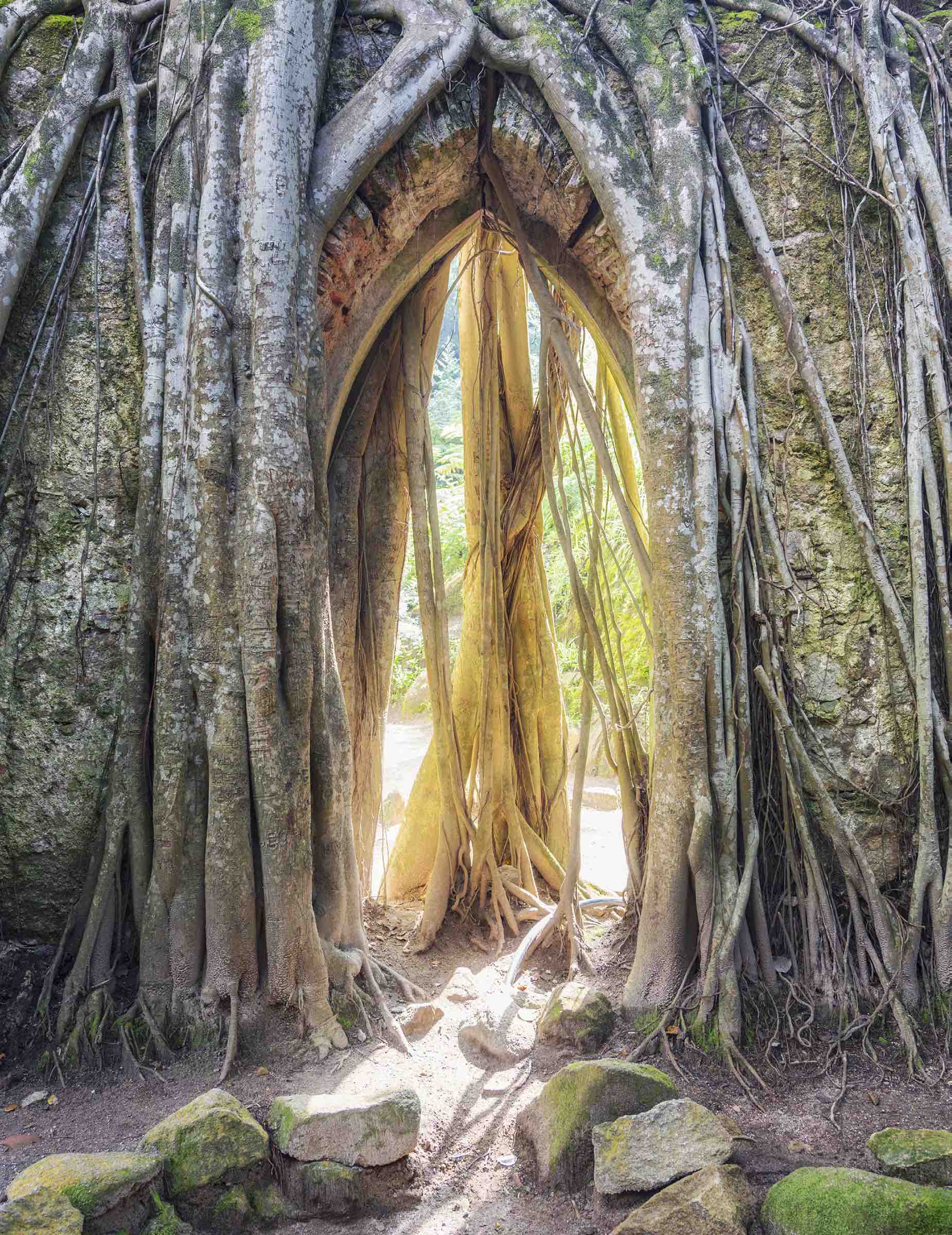

Inside a roofless church, sculptures crumble in the grip of strong vines. A glass conservatory shatters as the plants once grown inside reach for the manor house just beyond the windows. What used to be a stone portal is cupped in tree roots that echo its gothic shape. Spirits of the original builders flit through the architecture as it succumbs to ever insistent nature.

Enchantment grows in ruins.

Such places are points of contact with the past and, according to photographer Aurélien Villette, our windows into the future. “A ruin is not something finished,” he says. “It is constantly evolving.”

Villette’s photographs capture place and time in precise detail, with a clarity that makes the moment as vivid and present as if we are standing there ourselves. It looks almost too real to believe—and in that heightened awareness of reality, we enter a state of dreams.

Dreams of the past, of the future, encountered through a serendipitous but fleeting present moment, a quick-moving beam of light. Dreams in which we imagine what we might become.

When I talk to Villette, the quarantine has just lifted from Paris, where he lives. As soon as it happened, he took a train heading south; he speaks to me now on his mobile phone, after searching for a shelter from the wind blowing over the high plateaus of the Auvergne region of France. He tells me he’s gazing out at his next morning’s subject, a group of centuries-old stone farmhouses crumbling into the soil.

“These stone houses were completely ordinary when they were built,” he says, “and now they are abandoned and disappearing into the countryside. In some places you will find museums that explain how people used to live here, but it’s mostly a lost heritage. These houses would be too expensive to build now. We see a spark of what life was like hundreds of years ago, just as the last traces are melting away.”

Villette has photographed ruins in Russia, Jordan, Italy, Japan, and the United States, among other places. His subjects are well off the beaten path, and some of his favorites are all but forgotten—painted caves that have served as both church and shelter during long-ago wars, for example. So how does he find these magical locations?

“There are many different ways,” he says. “I’ve done a lot of research in books and libraries—and on the internet, which is becoming more and more important—and I’m also part of a network of people who look for these vanishing architectural sites.”

For a new explorer, he recommends starting with articles in local newspapers. The interest in ruins is growing, and more and more has been written about where to find them—even very close to home.

It is true, he says, that the ruins that feel most authentic and unspoiled may be remote and hard to reach. Some forgotten treasures have stayed unnoticed for decades or even centuries. “Sometimes I feel as if I am the first person to have seen one of these places,” he says. “At least, I am the first to see it in this way, as a ruin. And then I want to bring it home for people who haven’t been able to travel there yet—so I take these photographs.”

Practically, this means Villette has camped alone in spots where his tent was the one point of light on the ground and a cold wind swirled around him. “Sometimes the work is a hardship,” he admits, “but it’s like love—it can make you sad or happy. And for me, the difficulties are part of the dream.”

But, he says, it isn’t necessary to travel far in order to find one of these magical places. No matter where you live, there is bound to be some site that has fallen into decline. One of his many prize-winning series featured decaying theaters in the United States. I also mention barns tumbled down into pastures, abandoned amusement parks, ghost towns in the mountains of Colorado or New Mexico. “And old movie theater façades in town,” he adds, “with art deco elements that put you into the world of vintage films.” In short, simply push into your own land- and cityscape, and you will find your own portal to the past.

I have to wonder how such a nomad treats his own home. Does he decorate it, or is it more like another way station in his journey toward grander places?

Yes, he says, he has decorated, especially during the year of Covid. As he travels, he collects small tokens—“objects without any value, such as a pebble or a little flag”—and arranges them on an étagère.

“Taken together, they are a narrative of my life,” he says. “It would not make sense to anyone but me, but I remember where I found each thing, no matter how ordinary and unspecial it seems.”

When France issued the order to shelter in place, he was in Argentina on a photographic expedition. He packed up and hurried home, then spent a year living—like many of us—in his imagination, reflecting on his past and fantasizing about what might happen after this long moment of suspense.

He grew up in a very old house in a small village, and his mother encouraged his interest in art. But computer skills came easily, and he spent years in the field. “I missed art during that time,” he tells me. “I realized that to live is to think.” So he trained himself to take photographs with the precision of an engineer and the soul of an artist.

He was drawn immediately to ruins because exploring them—even if you are only looking at a picture and not taking it—can be a meditative experience. We come to a new understanding of the past and future, and of ourselves as guardians of both: “These are bits of the past that survive in our modern world and are crumbling into it in the present. They give us a way to encounter other ways of thinking … Of course, we can never know exactly what life is like for another person, but we can begin to get the feel of it. We connect with people who are long gone. And we also create our own relationship with the future, as we think about what will happen to this ruin next.”

As plant life tugs a pile of stone back toward the ground from which it rose, new holes open up to the light and train our eyes to see differently. That’s part of the magic.

“To really understand the light that shines outside, you have to go deep inside. See it from a new place in a new way … Sometimes I go down into the earth just to see how the light shines from above.”

To enter the Sicilian church in the first photograph here, for example, you have to begin belowground, passing through the primeval grottos that were sacred to a culture that came long before the church. One sacred space was built on top of the other, and the church itself was remodeled several times. Then, above, a burst of light from the empty window changes the idea of what light itself is.

I am reminded of the 13th century mystic poet Rumi, who wrote, “The wound is the place where the light enters you.” In Villette’s work, the light is first nostalgia, then beguilement, inspiration, finally a sense of hope and connection to both past and future through a bright single moment. Villette’s photographs shine the light into us.

It’s dark now in the Auvergne and getting chilly. Villette still has to set up a tent to sleep in and plan his shots for the next day. We say a quick goodbye, and our conversation becomes one more small event sunk into the stones he will photograph tomorrow.

We all have these special places, our own gorgeous ruins where we look backward into a past populated by spirits barely known, and forward to our own futures. And in these places we know: We are the enchantment.