As the nights grow longer and colder, my mind always turns to love. Actually, my mind turns to love and cake because both are comforting and keep you warm, albeit in different ways. By coincidence, winter holds an occasion when I can indulge my love of both—Saint Agnes’s Day on January 21, when lovelorn girls can see a fleeting vision of their future lovers by paying tribute to Saint Agnes. As we are all in need of cheering up in these socially distanced, worrisome times, I won’t tell you exactly why Saint Agnes is the patron saint of virgins, but as you can imagine, it wasn’t pretty. It mainly involved people being struck blind, uncontrollable hair growth, and a beheading, but let’s not dwell on that. Given the bother she went through to preserve her virginity, it seems a little off that on the eve of Agnes’s feast day ever since, girls have gone through rituals to cop a sight of their future lovers. Sorry Saint Agnes, but we are shallow, lovestruck creatures at heart, and who doesn’t love a ritual?

The Victorians adored rituals, embracing old ones and embellishing them with all manner of frippery. They particularly cherished those that divined love, reassuring the unmarried and alone that somewhere a heart burned brightly for them. You are probably familiar with John Everett Millais’s The Bridesmaid (1851), a painting of a beautiful young woman with hair abundantly shimmering down her shoulders. She is gazing into the future as she passes a piece of wedding cake through a ring nine times, hoping a vision of her future lover will appear in the mirror. She is looking very determined, although judging by the size of her sugar shaker, she is destined for disappointment.

If you really can’t wait for the next wedding to roll around to indulge in a little matrimonial divination, then Saint Agnes’s feast offers virgins the opportunity to practice all manner of rituals, including the baking of a “dumb” cake, named after “doom” or fate, which involves water, flour, and salt. You and three of your close friends gather in the dead of night to create, bake, and slice this mystical salty brick in absolute silence. With eager anticipation of visions of your handsome young lover, you then take your lump of cake, walk backwards up the stairs, and place it under your pillow. Your dreams will be filled with your heart’s desire, even if it takes until spring to get the crumbs out of your bedsheets.

The great Victorian poet Alfred, Lord Tennyson wrote a poetic tribute to the feast of the patron saint of virgins in which he celebrated the cold of the January night and the piousness of young nuns, who are seemingly so cold they hope to die.

My breath to heaven like vapour goes;

May my soul follow soon!

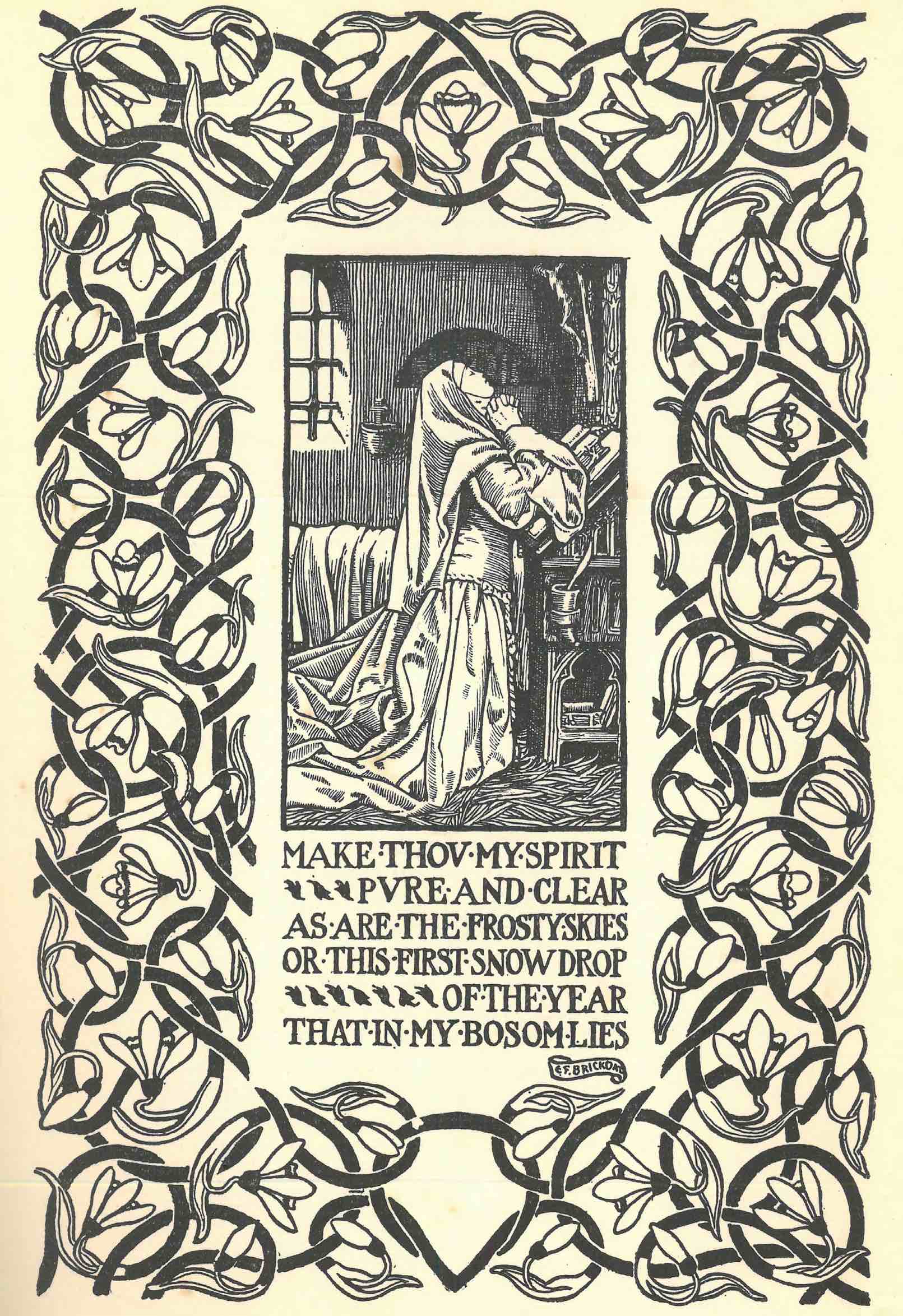

Now that really isn’t the attitude to take, but it did inspire the most beautiful illustrations, first from John Everett Millais again, this time with a very Edward Gorey–esque girl pausing on a stairwell to gaze out at the snow, a misty cloud of her breath in front of her. For a proper epic vision of the scene, you can rely on Eleanor Fortescue Brickdale, who gives us a riotous illustration for an otherwise short poem. Her young nun knees in prayer, asking

Make Thou my spirit pure and clear

As are the frosty skies,

Or this first snowdrop of the year

That in my bosom lies.

While I admire the dedication of these young women, I would rather turn to Keats to keep me warm …

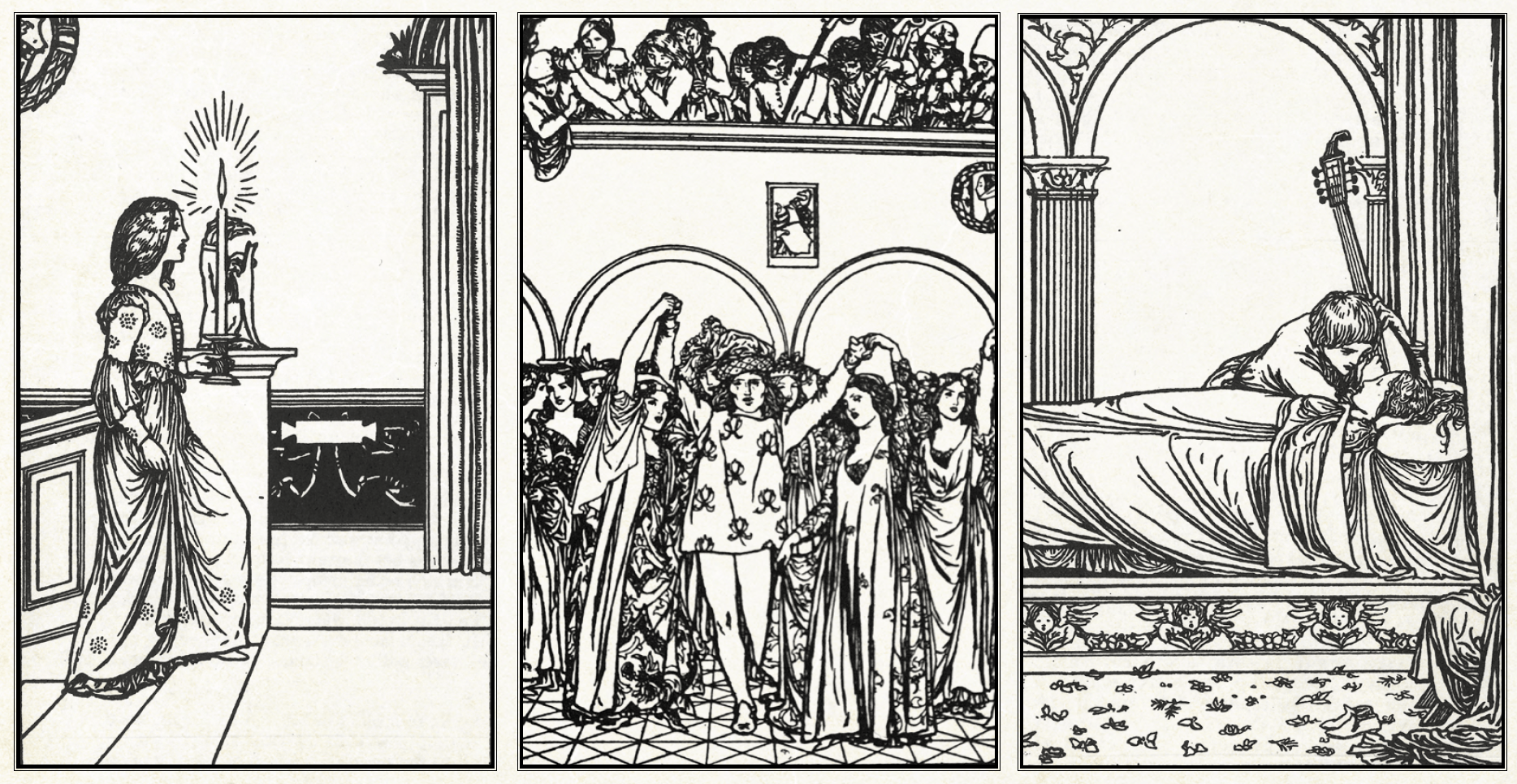

The most famous tribute to the rituals of Saint Agnes’s Eve and its romantic opportunities was John Keats’s poem “The Eve of Saint Agnes” and 19th century artists and illustrators found the plight of the young protagonists Madeline and Porphyro to be the inspiration they needed for visions of their own. Keats used Saint Agnes’s eve as the backdrop to a poem about two warring families and their amorously attached offspring. Young Madeline is desperate for “soft adorings” from her love, who will appear, according to the poet, “upon the honey’d middle of the night.” Robert Anning Bell, in a 1897 illustrated edition of Keats’s poems, showed Madeline traipsing up the stairs to bed with a very serious expression, but unsurprisingly, most Victorian artists, inspired by this magnificent romance and drama of a poem, decided to show the moment when Madeline took her frock off for bed. Daniel Maclise, in his 1868 painting, showed our heroine letting down her hair with her frock falling off in a magnificent bedroom, dappled by stained glass. Behind her, she has a Saint Agnes statue on plinth and an open Bible, just in case you were in any doubt that she is a very good girl indeed.

When John Everett Millais came to portray the same moment—frock falling off, corset ahoy—he chose an almost noir-ish half-light and our heroine stilled by the very pious thoughts that occur when one has one’s bosom out in a chilly room. When he painted the scene, Millais got his beautiful young wife Effie to pose in her underclothes in the manor house at Knole Park in Kent. She is stood at the foot of a bed that King James I once slept in, and the room was apparently freezing. I bet not all of Effie’s thoughts were pious at that moment—having just escaped a disastrous marriage with the celebrated art critic and general oddity John Ruskin, she married Millais, but I’m sure while posing in her petticoat in the middle of winter she was thinking, My first marriage was appalling, but at least I got to keep my jumper on. Turning back to the poem … while she sleeps, Madeline’s family are having a right old knees-up in the castle. They obviously did not get the message about abstinence, salty cake, and opening windows as much drunken revelry is taking place. I particularly like Anning Bell’s illustration of “the argent revelry,” which is exactly how I like my revelry also. In outrageous ignorance of social distancing, the man in tights seems to be getting on very well with a couple of women. I’m not sure that if I was at war with rival families, I’d ever feel relaxed enough to get blind drunk and dance with abandon, but I suppose it’s important to take an evening out of your feuding and have a bit of me time. All this partying means that the object of Madeline’s love, young Porphyro, can sneak in and see his beloved.

For romantic reasons, Porphyro had managed to get into the castle, which can’t have been too onerous seeing as most of its occupants were three sheets to the wind, and hid himself in his beloved’s bedchamber. As Madeline sleeps, Porphyro sneaks out to gaze upon her lovely face. This scene also proved popular with artists, to differing results. Arthur Hughes saw the romantic reunion as the hero kneeling by his beloved’s bedside, gazing on her in wonder at her loveliness. That, I must admit, is preferable to his watercolor version where Porphyro awakens his love with a burst of lute music, which is very romantic as long as he is good at the lute and didn’t choose Robin Thicke’s “Blurred Lines.” Mind you, all that is slightly less weird than what happens in the poem when Porphyro decides that the best and most charming way to beguile his beauty from her slumber is with a load of fruit or possibly Turkish delight, filling her room with fragrance from golden plates and silver baskets and then grabbing her lute and playing “La Belle Dame Sans Merci.” The “belle dame” bit is flattering, the “sans merci” bit comes off as a bit needy, but still Madeline is utterly beguiled by Porphyro’s fruit-and-lute combo.

The couple decides that there is no better time to run away together, away from her appalling drunken family and drafty castle, into the night. Their stealthy escape appealed to artists such as William Holman Hunt, who showed the couple sneaking past the inebriated guards and possibly equally sozzled dogs. Through the arched windows you can see the revelry still in full swing, but our handsome hero, in some very interesting tights and an unexpectedly phallic belt, can tiptoe off to a romantic future. The bloodhounds in Arthur Hughes’s vision of this final scene seem to be aiding and abetting the happy couple off into the night, not in any danger of giving the game away. You can imagine them sliding the bolts back with their massive paws and muttering, “Go on, off with you, you’re too good to be here. I’ve had nothing but gin in my water bowl for the last forty-eight hours. That’s no way to carry on.” With the blessing of the bloodhounds, the besotted couple vanish into the night, leaving the revelers to fall into nightmare-infested sleep—but that might well have been the gin.

So, dear reader, if we have learned anything from Keats and his artistic acolytes, it is surely this—the course of true love is helped by fruit, a lute, and a martyred saint, but quite honestly, as the nights draw in and the future seems uncertain, I would suggest you have another slice of cake and dream of handsome men in tights …