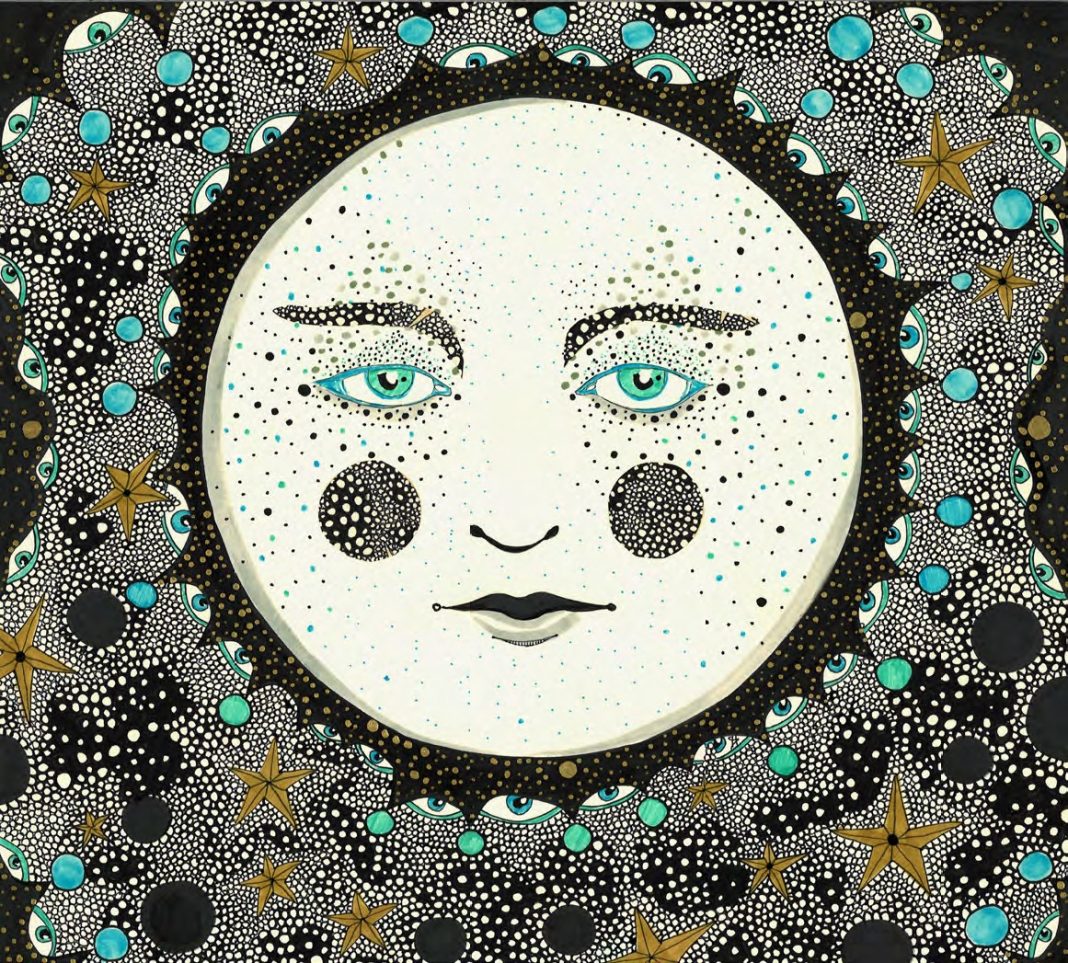

Illustration by: © Daria Hlazatova

I was mad for Moon Maid. As illustrated by Chester Gould, she was buxom with hypnotic, lushly lashed eyes, a platinum-blonde bouffant, a perky pair of antennae, and thigh-high go-go books. (Quote from a news reporter: “Oh boy! This Moon Maid may be too HOT for Earth.”)

Gould’s fascination with technology sent the characters in Dick Tracy, his classic comic strip, to the moon throughout the 1960s, but after NASA actually landed men on the moon, Gould dialed back his space exploration. Moon Maid, however, remained on Earth, married to Tracy’s son Junior. I was a farm boy, far from any city and its dailies, so my only access to Dick Tracy was in the Sunday full-color funnies, and I remember Moon Maid’s skin as cotton-candy pink.

One summer Sunday in August, when I was ten, Moon Maid took Dick Tracy’s car keys to run an errand. A bomb had been planted in the detective’s car, and I watched, before church, as flames suddenly engulfed this young wife and mother. I’m sure I prayed hard. I spent the week certain that the next week’s strip would reveal how Moon Maid survived. How could she perish in such a crime-fiction cliché? Little did I know that Gould had retired from the strip, and his replacement, Max Allan Collins, was intent on ridding the strip of its moon phase. Moon Maid was dead, full stop.

While this summer marked the fortieth anniversary of Moon Maid’s murder at the hands of Max Allan Collins, next summer will mark the fiftieth anniversary of humans’ first steps on the moon. Prior to the moon landing, many earthlings, even astronomers, insisted on the presence of humanlike life on the moon. But since the moon landing, many conspiracy theorists have insisted the opposite. (Sci-fi author C. Stewart Hardwick credits technical writer Bill Kaysing as the first to publish such conspiracy theories about Americans on the moon: “He was not obviously insane,” Hardwick wrote on the website Quora, “but he was obviously unqualified to express the opinions he was expressing. My guess is, technical writing with objective criteria didn’t suit him, and pretending expertise to a bunch of ignorant sycophants fueled his ego.”)

At the heart of both perspectives on moon life is a kind of imaginative whimsy, it seems to me. Before we went to the moon, it was fun to speculate what kind of critters frolicked there; after the moon landing, it was fun to invent scientific theories that kept us grounded, the moon still magically unattainable. Even beyond the comics page, newspapers had a notorious connection to moonlings, even those spotted from earth by the naked eye:

“Great Astronomical Discoveries Lately Made by Sir John Herschel, L.L.D. F.R.S. &c” was the original title of a series of news articles that appeared in 1835 in the New York Sun. Sir John Herschel was a famed astronomer in the U.K., and while the U.S. awaited news of discoveries he made with an advanced telescope, the Sun capitalized on its readers’ curiosities by simply inventing fake news of moon colonies of strange creatures. After a lengthy description of the telescope itself, Richard Adams Locke (the newspaperman later credited, or discredited, with writing the series) gets to the moon’s inhabitants, which includes humanlike creatures that “averaged four feet in height, were covered, except on the face, with short and glossy copper-colored hair, and had wings composed of a thin membrane, without hair, lying snugly upon their backs, from the top of their shoulders to the calves of their legs.”

These “discoveries” first made money when presented as a factual report (the newspaper’s circulation increased rapidly) and then made even more money when published in a pamphlet that sold the fiction as a “hoax.” According to an introduction in a reissue of the pamphlet in 1856: “The proprietors of the journal had an edition of 60,000 published in pamphlet form, which were sold off in less than a month; and of late this pamphlet edition has become so scarce that a single copy was lately sold at the sale of Mrs. Haswell’s Library for $3.75.”

The Democratic Standard (1843), in a report about scientific discoveries of the moon’s surface, addresses the question “Is the Moon inhabited?” with a kind of poetic insistence:

“There, all is silent and dumb; a dreary and monotonous creation with not only nothing to stir, and nothing to enliven, but with no mind to be stirred, and no heart to be enlivened. And this was its fate for centuries, presenting an image of an eternity of desolation, the very idea of which was oppressive.” (The article also addresses the relationship between the moon and “insane people,” i.e. the “lunar” aspect of “lunacy”: “upon comparison of paroxysms of madness with the changes of the moon,” there was found to be no connection.)

Astronomers’ discoveries and speculations about the influence of the moon sparked both curiosity and skepticism. In a letter to the editor of the Wilmingtonian, in Delaware (1824), a snarky reader comments on a report on the moon’s influence on the weather and animal nature: “We shall now be able to do justice to that powerful goddess, hitherto deemed a fickle, uncertain, and whimsical coquette, but now ascertained to be a grave steady matron, as regular in her movements as Jupiter in his orbit, or as gravitation to the centre! … I say the ladies may now know, when preparing for a tea-party, whether to take their shawls, pattens and parasols, or to leave superfluity at home, and sally forth as trim as a maypole!!!”

The Gazette of the United States saw fit to reissue, as editorial content, an advertisement in 1794 regarding a woman who was crossing the London Bridge. A boy tugged on her skirts and insisted she look at the moon, and there she saw “great armies of soldiers, both horse and foot, pass over the orb.” She and the boy saw this happen several times as they watched the moon that evening. The advertisement requests that anyone who also happened to have witnessed this activity promptly report to “Mr. Clarson’s” in St. James’s Market.

The National Gazette in 1793 suggested that we should hope the moon reflects nothing about the earth: “If this earth, which is thirteen times larger [than the moon], and superior in every respect, exhibits such wretched scenes of blood, misery, and desolation, as we daily see or hear of, the moon, being no other than her kitchen, is by fair inference a world of war and vengeance, without the least interval of pacification, & the menials that inhabit her are undoubtedly a set of blackguards.”