“Matrimonial miseries, domestic unhappiness, social wretchedness, and national degradation; every evil under the sun will be found, if you go sufficiently far back, to have had its origin in whisky.”

—from “Grant’s Impressions of Ireland” in Tait’s Edinburgh Magazine for 1844

Whiskey (sometimes referred to as “whisk(e)y” in whiskey critique so the whiskey critic can acknowledge that whiskey is sometimes spelled “whisky” depending on the region) has bewildered, bedeviled, and bemused women for centuries, even as men have rigorously (and often chauvinistically) protected whiskey-drinking as a pleasure and vice exclusive to gentlemen and varmints.

It can be argued—and has been, especially by whiskey critics who are women—that whiskey has been both a symbol and a rite of exclusion. From blues tunes to cigar clubs, men have staked their claim on whiskey appreciation. They even proudly appreciate whiskey unworthy of it: swigging rotgut is a classic cliché of masculinity in westerns.

Even when marketing directly to women, whiskey dealers have emphasized that the drink is a little rough-and-tumble for delicate tongues. Women whiskey aficionados have successfully challenged such stereotypes and traditions. And though books such as Fred Minnick’s Whiskey Women: The Untold Story of How Women Saved Bourbon, Scotch, and Irish Whiskey have outlined the roles women have played in the development of whiskey around the world, this all works against decades of the popular notion that it’s manly to love whiskey too much (no matter how bad it might be) and womanly to hate it (for its taste, but also because men love it too much).

Here are a few glimpses of women’s relationship with whiskey in centuries past:

+ Historical anti-liquor movements, such as temperance unions and prohibition campaigns, were often led by women and blamed on women. Saloons were considered a threat to family, and the popular imagination enjoyed portraying women in protest. While some women held prayer vigils outside saloons, others took a different tack. Under the title

“Spunky Women,” a news item in 1854 described forty to fifty women of Winchester, Indiana, visiting “the different rumsellers in town” following the death by whiskey of a local man. They demanded the saloon keepers sign an agreement to sell no more liquor; if they didn’t sign, the women busted up the bottles behind the bar.

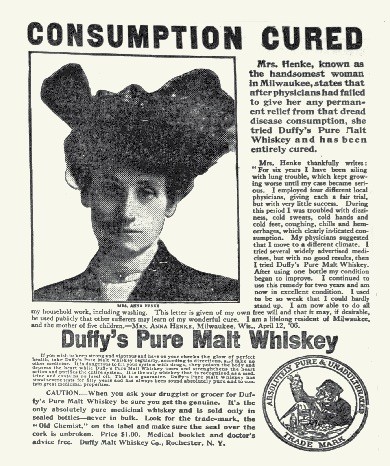

+ Though counties refused to outlaw liquor, many of them did outlaw women from getting near it (and this is perhaps responsible for some women’s disgust for saloons). Women were forbidden from bars and clubs throughout the 1800s, but ads for “medicinal” whiskies and other potent cure-alls (in the years before FDA approval) kept local newspapers in business. Ads for Duffy Barley Malt Whiskey were often testimonials by “analytical chemists,” as well as doctors, ministers, and the women who drank it. A Duffy ad that ran in several papers in 1886 looks like editorial content (under the headline “Facts About Whiskey”) and asserts that “women, from the peculiar character of their organism, frequently need pure whiskey stimulant, and with them it is indispensable.”

+ Ads for Duffy’s included the following spokeswomen: Mrs. Henke, “known as the handsomest woman in Milwaukee,” who was cured of consumption after physicians failed her; Miss Susie John Cotton, who came down with pneumonia while traveling by train and was given Duffy’s by a minister; Miss Mae Rodgers was cured of bronchitis; and Frances Burton (116 years old), Mrs. Susan Baker (101 years); and Mrs. Priscilla Martin (93) attested to Duffy’s claim as “the Great Renewer of Youth.”

+ Lydia Pinkham, who inspired a line of curatives for women that were 18 percent alcohol, wrote a medical book in which she recommended partridgeberry wine, fortified port, and whiskey in milk for a stomachache. A 1907 ad for her spiked vegetable compound asserts that “a sickly, irritable, and complaining woman always carries a cloud of depression with her; she is not only unhappy herself but is a damper to all joy and happiness when with her family and friends.”

+ An ad for Tharp’s Berkeley Rye in 1901 features, in bold print, “A Whiskey Ladies Like” followed, in smaller print, by: “to have in the house for sickness and emergencies,” complete with a phone number for “family orders.” The ad goes on to boast that Tharp’s “has the distinction of being more imitated by unscrupulous dealers than any other in the market. Inferior goods are never imitated.”

Though newspaper advertising portrayed women as needing these liquor-laced patent medicines (some of which also contained morphine and cocaine) to address their distinctly feminine problems, the newspaper’s reporters often attributed crimes to a deadly combination of whiskey and women. Everything from suicide and embezzlement was initiated by “whiskey and women,” though there were never women at any of the scenes of these crimes (and, indeed, women were sometimes the victims). Here’s just a sample:

+ The following quote was tossed around in the mid-19th century, as early as 1856, perhaps providing decades of criminal motivation: “The five great evils of life are said to be standing collars, stove pipe hats, tight boots, bad whiskey, and cross women.”

+ In the News and Notions section of an 1880 edition of the Mower County Transcript (Lansing, Minnesota): “Whiskey, women and cards are said to be the rocks on which mail agent Ed. Keeler foundered. Either one of these cursed evils are enough to ruin a man, but from the three combined, there could be no escape.”

+ As train robbers stood on a scaffold, about to be hanged, “they made statements attributing their downfall to whiskey, women and bad company,” according to the Scranton Tribune in 1894.

+ A man murdered his lover, and was sentenced to hang; he blamed, in a letter quoted in an 1897 article, “whiskey drinking, bad women, game and deceit.”

+ An escaped convict in Tampa in 1907 declared that “whiskey, women, and cards caused my downfall.”

+ The Santa Fe New Mexican in 1904 reported on a group of men in a brawl that led to a knife fight. Though no women were present, nor mentioned in the article, the headline declared: “Whiskey and Women the Cause.”

+ Back in 1882, such attribution seemed to already be recognized widely as cliché. A Kentuckian wrote teasingly to the editor of a Louisiana paper: “Possibly you will not seriously object to a few lines from this land of good whiskey, pretty women and fast horses.”