Photography by Kristin Reimer

Insect hotels are a creative and easy way to add a functional feature to your garden or landscape. Their purpose is to attract beneficial insects to your property. Although creepy-crawlies may not be your idea of welcome visitors, the health of our food system depends on them. Without pollinators we would not have fruits or vegetables. Without predatory insects, our flowers would be decimated. If it weren’t for the ground-dwelling insects, our plants would be gasping for air and suffocating in organic matter. Plus, insects are really cool and occasionally downright enchanting.

An insect hotel is a man-made replica of the natural habitats insects search for in the wild. When constructing them, the most important feature to keep in mind is that they should be as natural as possible. Look around your yard for inspiration. Each type of insect generally requires a specific material for its nesting site.

Mason bees, or Osmia, are an easy first guest. With them, you can be a beekeeper without having to do all the work involved in keeping honey bees. This is because they are solitary insects who use tubular burrows to lay eggs. These holes are usually left behind by woodpeckers or mice that make natural pockets in trees, logs, or any other protected cavities such as hollow twigs or a snail shell. Mason bees also easily adapt to man-made structures with predrilled holes or attractively arranged reed bundles. They’re named after their habit of building with mud, clay, or grit, which they use as masonry to build their nests. One especially fancy species of mason bee even uses flower petals to line their nest.

The orchard mason bee (Osmia lignaria) and the blueberry bee (Osmia ribifloris) are both native to the Americas. They’re nonaggressive and safe to approach and observe at a close distance. They very rarely sting unless handled roughly, and when they do, it is far less painful than the stings of other bees. Considered super pollinators, they have fuzzy bellies that spread lots of pollen as they flit quickly from flower to flower. These metallic green or blue bees are smaller than a honey bee and do not produce honey or beeswax. All females are fertile and build their own nests. The males emerge first from the cocoons they wintered in and anxiously await the females at the edge of the nest. After mating, the male dies and the female prepares for motherhood alone.

Setting out for provisions, she visits thousands of flowers to collect nectar and pollen. She then chooses her nesting location and begins by filling a cell with the food and laying a single egg on top. She creates a partition of mud that doubles as the back wall of the next cell. She continues this process until she’s filled the cavity. Female eggs are laid in the back of the chamber, while males go toward the front. Once finished, this supermom will plug the entrance of the tube and search for another location while the baby bees go through two phases of metamorphosis inside their individual chambers. The larvae spins a cocoon and becomes a pupae, and remains snug as a bug all winter long. Come spring, they emerge as adults and the cycle begins again.

Visit Jennifer Muck-Dietrich online at ediblewisdoms.com. Follow Kristin Reimer on Instagram @photomuse_kristin.

To construct your own Mason Bee hotel, you will need:

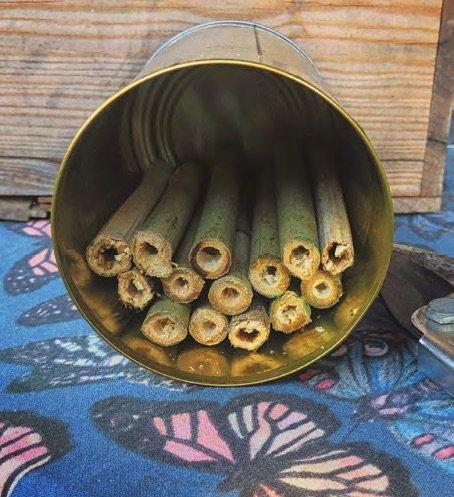

1 clean tin can (label removed and open at one end)

2 bamboo poles, ½-inch in diameter and 3 feet long

Loppers or strong hand clippers

2 feet of twine

Marking pen

Gloves

Ruler

Heavy grit sandpaper

Measure the length of your tin can and then, measuring with the pen, mark the bamboo poles into sections of that same length. You’ll end up with approximately 20 sections.

Wearing gloves to avoid getting splinters, carefully cut each section off and sand the ends to ensure they are smooth. Lay the can on its side and place the bamboo tubes inside, filling the entire can. The tubes should fit tightly inside and not slide out. You may need to wedge extra bamboo pieces in to ensure a tight fit. Wrap the twine twice around the can about a third of the way from the back of the can. Secure it with a strong square knot. You want the can to hang ever so slightly downward to avoid rain finding its way in.

Hang approximately 5 feet high, in an eastern-facing direction. Choose a sheltered location in your garden—against a fence or structure is good for blocking winds and keeping the bees safe and cozy all winter long.